The HTTP specifications 1.0 ([RFC 1945] and 1.1 [RFC 2068]) define the HTTP message formats. There are two types of HTTP messages, request messages and response messages, both of which are discussed below.

Below we provide a typical HTTP request message:

GET /somedir/page.html HTTP/1.1

Connection: close

User-agent: Mozilla/4.0

Accept: text/html, image.webp, image.webp

Accept-language:fr

(extra carriage return, line feed)

We can learn a lot my taking a good look at this simple request message. First of all, we see that the message is written in ordinary ASCII text, so that your ordinary computer-literate human being can read it. Second, we see that the message consists of five lines, each followed by a carriage return and a line feed. The last line is followed by an additional carriage return and line feed. Although this particular request message has five lines, a request message can have many more lines or as little as one line. The first line of a HTTP request message is called the request line; the subsequent lines are called the header lines. The request line has three fields: the method field, the URL field, and the HTTP version field. The method field can take on several different values, including GET, POST, and HEAD. The great majority of HTTP request messages use the GET method. The GET method is used when the browser requests an object, with the requested object identified in the URL field. In this example, the browser is requesting the object /somedir/page.html. (The browser doesn't have to specify the host name in the URL field since the TCP connection is already connected to the host (server) that serves the requested file.) The version is self-explanatory; in this example, the browser implements version HTTP/1.1.

Now let's look at the header lines in the example. By including the Connection:close header line, the browser is telling the server that it doesn't want to use persistent connections; it wants the server to close the connection after sending the requested object. Thus the browser that generated this request message implements HTTP/1.1 but it doesn't want to bother with persistent connections. The User-agent: header line specifies the user agent, i.e., the browser type that is making the request to the server. Here the user agent is Mozilla/4.0, a Netscape browser. This header line is useful because the server can actually send different versions of the same object to different types of user agents. (Each of the versions is addressed by the same URL.) The Accept: header line tells the server the type of objects the browser is prepared to accept. In this case, the client is prepared to accept HTML text, a .webp image or a .webp image. If the file /somedir/page.html contains a Java applet (and who says it can't!), then the server shouldn't send the file, since the browser can not handle that object type. Finally, the Accept-language: header indicates that the user prefers to receive a French version of the object, if such an object exists on the server; otherwise, the server should send its default version.

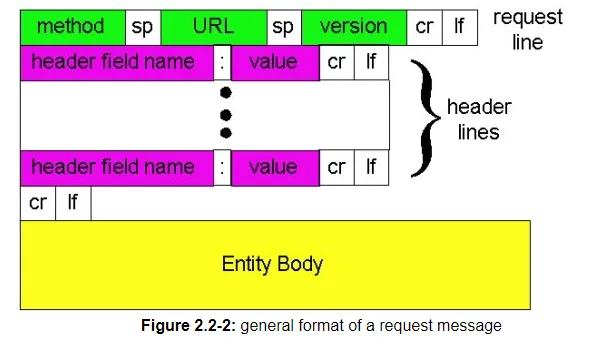

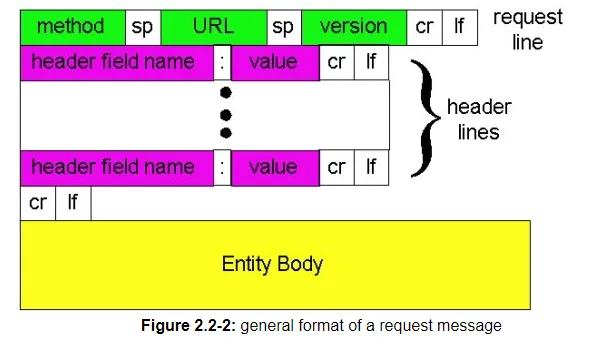

Having looked at an example, let us now look at the general format for a request message, as shown in Figure 2.2-2:

We see that the general format follows closely the example request message above. You may have noticed, however, that after the header lines (and the additional carriage return and line feed) there is an "Entity Body". The Entity Body is not used with the GET method, but is used with the POST method. The HTTP client uses the POST method when the user fills out a form – for example, when a user gives search words to a search engine such as Yahoo. With a POST message, the user is still requesting a Web page from the server, but the specific contents of the Web page depend on what the user wrote in the form fields. If the value of the method field is POST, then the entity body contains what the user typed into the form fields. The HEAD method is similar to the POST method. When a server receives a request with the HEAD method, it responds with an HTTP message but it leaves out the requested object. TheHEAD method is often used by HTTP server developers for debugging.

Below we provide a typical HTTP response message. This response message could be the response to the example request message just discussed.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Connection: close

Date: Thu, 06 Aug 1998 12:00:15 GMT

Server: Apache/1.3.0 (Unix)

Last-Modified: Mon, 22 Jun 1998 09:23:24 GMT

Content-Length: 6821

Content-Type: text/html

data data data data data …

Let's take a careful look at this response message. It has three sections: an initial status line, six header lines, and then the entity body. The entity body is the meat of the message – it contains the requested object itself (represented by data data data data dat …). The status line has three fields: the protocol version field, a status code, and a corresponding status message. In this example, the status line indicates that the server is using HTTP/1.1 and that that everything is OK (i.e., the server has found, and is sending, the requested object).

Now let's look at the header lines. The server uses the Connection: close header line to tell the client that it is going to close the TCP connection after sending the message. The Date:header line indicates the time and date when the HTTP response was created and sent by the server. Note that this is not the time when the object was created or last modified; it is the time when the server retrieves the object from its file system, inserts the object into the response message and sends the response message. The Server: header line indicates that the message was generated by an Apache Web server; it is analogous to the User-agent: header line in the HTTP request message. The Last-Modified: header line indicates the time and date when the object was created or last modified. The Last-Modified: header, which we cover in more detail below, is critical for object caching, both in the local client and in network cache (a.k.a. proxy) servers. The Content-Length: header line indicates the number of bytes in the object being sent. The Content-Type: header line indicates that the object in the entity body is HTML text. (The object type is officially indicated by the Content-Type: header and not by the file extension.)

Note that if the server receives an HTTP/1.0 request, it will not use persistent connections, even if it is an HTTP/1.1 server. Instead the HTTP/1.1 server will close the TCP connection after sending the object. This is necessary because an HTTP/1.0 client expects the server to close the connection.

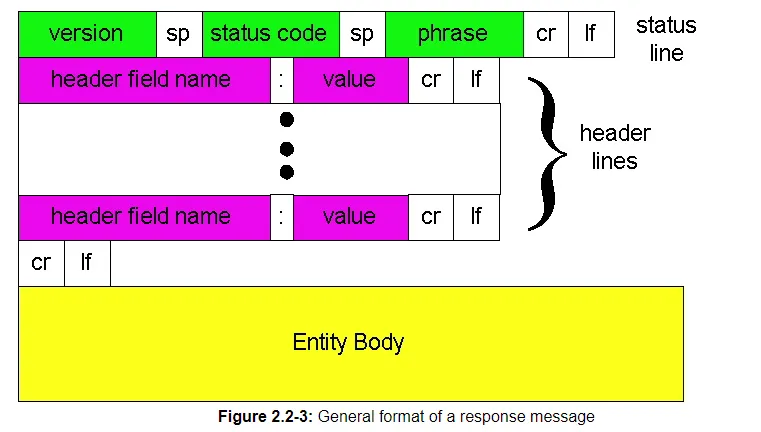

Having looked at an example, let us now examine the general format of a response message, which is shown in Figure 2.2-3. This general format of the response message matches the previous example of a response message. Let's say a few additional words about status codes and their phrases. The status code and associated phrase indicate the result of the request. Some common status codes and associated phrases include:

How would you like to see a real HTTP response message? This is very easy to do! First Telnet into your favorite WWW server. Then type in a one-line request message for some object that is housed on the server. For example, if you can logon to a Unix machine, type:

telnet www.eurecom.fr 80

GET /~ross/index.html HTTP/1.0

(Hit the carriage return twice after typing the second line.) This opens a TCP connection to port 80 of the host www.eurecom.fr and then sends the HTTP GET command. You should see a response message that includes the base HTML file of Professor Ross's homepage. If you'd rather just see the HTTP message lines and not receive the object itself, replace GET with HEAD. Finally, replace /~ross/index.html with /~ross/banana.html and see what kind of response message you get.

In this section we discussed a number of header lines that can be used within HTTP request and response messages. The HTTP specification (especially HTTP/1.1) defines many, many more header lines that can be inserted by browsers, Web servers and network cache servers. We have only covered a small fraction of the totality of header lines. We will cover a few more below and another small fraction when we discuss network Web caching at the end of this chapter. A readable and comprehensive discussion of HTTP headers and status codes is given in [Luotonen 1998]. An excellent introduction to the technical issues surrounding the Web is [Yeager 1996].

How does a browser decide which header lines it includes in a request message? How does a Web server decide which header lines it includes in a response messages? A browser will generate header lines as a function of the browser type and version (e.g., an HTTP/1.0 browser will not generate any 1.1 header lines), user configuration of browser (e.g., preferred language) and whether the browser currently has a cached, but possibly out-of-date, version of the object. Web servers behave similarly: there are different products, versions, and configurations, all of which influence which header lines are included in response messages.