Hydraulics of Wells

Flow to a well considered here is a radial flow of infinite areal extent that will be discussed for both steady and unsteady cases. Water wells are installed in an aquifer to provide water supply, recharge, or for observation. Observation wells are used to collect water samples and to monitor water levels. Some applications of well hydraulics are to avoid overpumping by managing groundwater discharge or recharge1, to prevent saltwater intrusion or pumping from other pollution source or storage, and to estimate field parameters such as hydraulic conductivity from pumping tests.

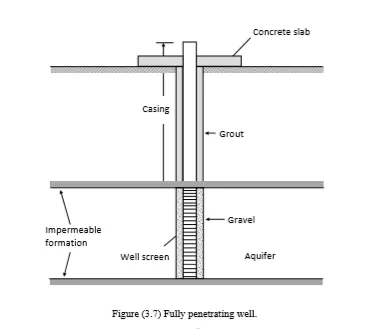

As shown in Figure (3.7), a water well consists of a casing and well screen. Well casing serves as a lining to maintain an open hole to the aquifer. The casing is usually grouted to prevent subsurface pollution flowing into the aquifer and to protect the casing from corrosion. A concrete slab is also placed around the casing to prevent surface pollution. The screen provides a maximum amount of water supply with a minimum hydraulic resistance. A gravel pack is placed around the screen to minimize pumping sand and to maintain a high permeability zone. This section provides the governing equations for radial groundwater flow by assuming that the pumped well is fully penetrating the aquifer. However, in some practical cases, it is not necessary to install wells with full penetration especially where the aquifer is very deep and the water

requirement is moderate. With partial penetration, actual flow velocities will have components in the vertical direction. The assumption that flow toward the well is horizontal may no longer be valid. Nevertheless, the effect of partial penetration becomes negligible on the flow pattern beyond a radial distance larger than about 1.5 times the aquifer thickness (Todd and Mays, 2008). Under this consideration, the governing equations provided for fully penetrating wells may be used without appreciable error.

Steady Flow to a Well If a well is pumped continuously for a long period, a steady state is reached implying that piezometric head changes in space but not with time. In this case, the hydraulic conductivity of the aquifer becomes an important property for modeling the radial flow.

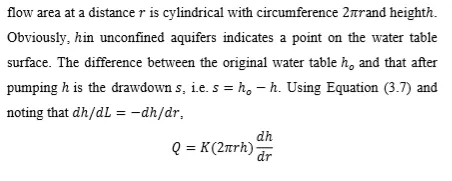

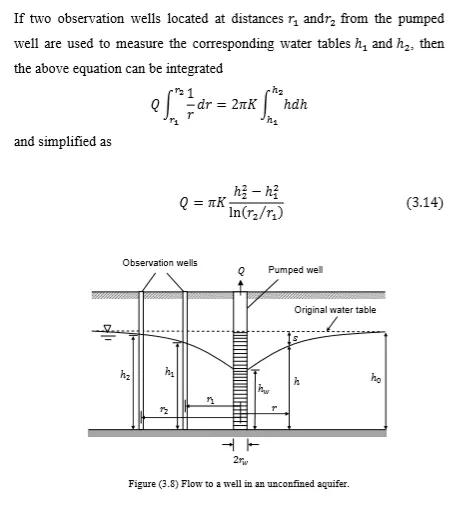

Unconfined Aquifer Consider a pumped well fully penetrating an unconfined aquifer as shown in Figure (3.8). If the water table is initially horizontal, then a circular depression would develop since no flow can take place without a gradient toward the well.