The Very Real History Of Death Stars

Space stations are reflections of those who build them. Some, like the International Space Station and the proposed Lunar Gateway, are shared spaces that humanity can use as a springboard from our home planet. And then there are armed space stations, bringers of doom from above.

In Star Wars, an armed space station could harness enough power to crack entire planets. The Death Star's level of destruction is a sci-fi pipe dream, thank goodness. But that hasn't stopped very serious military minds from developing and even launching very real armed space stations.

Some resemble the Galactic Empire’s killer that's-no-moon more than others, but they share one common goal that Darth Vader would appreciate: dominating a planet from orbit.

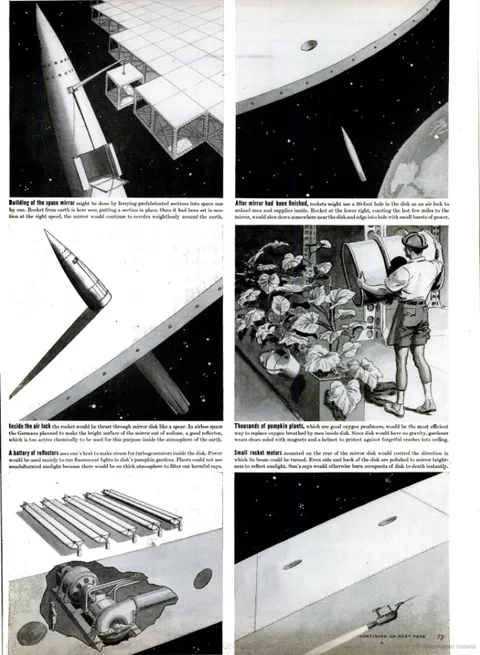

Illustration of Germany’s space mirror, 1945.

LIFE ARCHIVES/GOOGLE BOOKS

The first example of legitimate death star engineering comes at the dawn of the space age. After World War II, U.S. Army technical experts poured over the remains of the Nazi military industrial complex, finding aircraft designs, missile technology, and plans for

an orbital weapon of mass destruction. A Life magazine article from 1945spells out the details saying, “Nazi Men of Science Seriously Planned To Use a Manmade Satellite As A Weapon for Conquest.”

The plan started with good intentions, according to Life, before the outbreak of World War II. Herman Oberth, a legendary aerospace designer who would go on to design the V-2 for Germany and the Saturn V for the U.S., in 1929 devised plans for an orbital base.

Parked in geosynchronous orbit, it would serve as a refueling station for spaceships setting out to explore the solar system. The newly proposed Lunar Gateway, a joint operation between NASA and Roscosmos, would have a similar function.

LIFE ARCHIVES/GOOGLE BOOKS

But the war brought a new idea to the table: Make a space station, put it at a lower orbit, and arm it with a giant mirror “to burn an enemy city to ashes or boil part of an ocean.” The station would be manned with a crew that, when not aiming the giant mirror

like a bully frying ants, would instead tend to pumpkin gardens.

The biggest obstacle for such a plan, the magazine claimed, was that no heavy rocket existed that could ferry the parts into orbit. “If the modern German scientists had been able to make such a rocket, they may have been able to set up their sun gun,” the article notes. “Whether the sun gun would have accomplished what they expected, however, is another matter.”

Getting the parts into space was only part of the challenge, and any handheld mirror can demonstrate the problem. Point the mirror so that light strikes the nearest wall, then tilt the surface so that it strike a wall that is farther away. The light is weaker and

wider on the far wall. The same sapping effect would afflict the power of space mirrors.

SCALE THAT UP TO A CITY KILLER, AND YOU’D HAVE A MONSTROUS, EXPENSIVE SPACE WEAPON THAT’S NEARLY IMPOSSIBLE TO MAINTAIN.

But parking sats in lower orbits, where the beam is stronger, means the ground below is moving at higher speeds, which is less than ideal because the beam needs to linger

on its target to spark fires.

Space reflectors do work, as the Soviet Union found in the 1990s when they launched one to bring light to Siberia in the 1990s. A 65-foot-diameter space mirror called Znamya beamed about three full moon’s worth of light across 2.5-miles of the earth’s surface. Scale that up to a city killer, and you’d have a monstrous, expensive space weapon that’s nearly impossible to maintain.

Although the sun gun never came to fruition, the specter of a Nazi base parked in orbit sparked the imagination of other militaries, and it wouldn’t be the last “death star” plan attempted.

Baikonur Cosmodrome, 1975.

On April 3, 1973, at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in modern-day Kazakhstan, the Proton rocket roared from a snowy spaceport, rising into the air and tearing out of Earth’s gravity well. Inside its nosecone was a space station known to the public as the Salyut 2, part of a Soviet civilian program to establish a toe-hold in space. But that’s a lie. At the center of the highly classified program, the Proton’s payload is the world’s first military space station, called Orbital Piloted Station-1.

A crew was ready to journey to the OPS-1 station 10 days later, but the Proton fuel tank exploded after the station was deployed. The debris whirled around the Earth and violently caught up with OPS-1 two days later. The manned rendezvous was eventually canceled, but other launches would bring more cosmonauts—and weapons— to space.

Over the years, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union established military outposts 1,200 miles above our heads. First came recon missions, using manned stations in orbit to keep an eye on each other. The U.S. had its own secret military space station program, called the Manned Orbital Laboratory, but was canceled in 1969 before any astronauts launched.

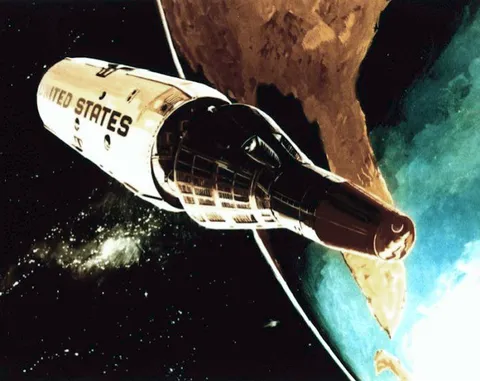

Illustration of the Gemini capsule separating from the Manned Orbital Laboratory (MOL).

The Russians, however, made more progress. OPS-2 would have a crew, and that crew would be able to defend itself with a 23mm cannon mounted to it. Modified from the tail gun of a Tu-22 bomber and carrying 32 explosive shells, the entire station would turn to aim at a threat.

The Russians even tested the space cannon, but they were worried about the shock of firing it, so they tested it after the space station inhabitants came back to Earth. It was a success, and space engineers designed future OPS stations to

carry missiles, but they never flew

The one difference between the Soviet’s armed space station and the Empire’s planet killer is that the cannons were never meant to fire on a planet. After all, if you’re in orbit you don’t need explosive shells to damage something. Drop a well-shaped chunk of metal onto a target from 1,200 miles up and the speed alone will cause massive damage, like a high-energy meteor impact.

The Soviets, instead, designed the modified space cannon to aim at other spacecraft. They foresaw shooting wars in orbit, something that is very much discussed in both Moscow and Washington today.

THE ONE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE SOVIET’S ARMED SPACE STATION AND THE EMPIRE’S PLANET KILLER IS THAT THE CANNONS WERE NEVER MEANT TO FIRE ON A PLANET.

In the end, unmanned satellites proved to be more economical and reliable than astronauts peering through scopes, so both militaries abandoned the idea of manned military space stations. But the idea persisted as engineers sought ways to target nuclear warheads as they crossed through space.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

The Star Wars defense initiative of the 1980s cast a wide net for ideas that could stop inbound nuclear warheads. People know about the plan to launch a spacecraft that could disable incoming nukes with X-ray lasers, but that’s a reactionary space weapon—not a permanent one.

The story of permanent, armed space stations within the Star Wars program is rarely discussed, but a 1989 paper written by for NASA by CalTech/Jet Propulsion Lab staff

gives a pretty good description of what the defense industry had in mind.

The NASA paper details ways to use an electromagnetic railgun to launch small satellites from a mothership in orbit. Railguns use electric currents to create powerful magnetic forces that can drive a projectile down a rail at tremendous speeds.

But the 1989 JPL paper proposed a peaceful, scientific application for EM guns that, the author says, would benefit from research being done by the Pentagon as part of the Star Wars missile defense effort. The public in the late 1980s was already aware of EM gun projects, but ones based on the ground shooting into space.

One project, called Compact High Energy Capacitor Module Advanced Technology Experiment (CHECMATE) made headlines, but it too was eventually canceled in 1992.

But there was another idea buried in the paper called Have Sting, which contemplated placing permanent railguns into orbit. “A large amount of the SDIO [strategic defense initiative organization] effort to date has been on space based EM launchers, ideal for

space science missions,” the paper says. “Several contractors including General Electric and Boeing participated in this program.”

Have Sting didn’t shoot chunks of metal, but spacecraft smart and tough enough to seek targets in space. “These spacecraft have remote sensing instruments that enable them to carry out their mission,” the paper describes. “These concepts were developed under the requirement to operate after being electromagnetically launched.”

“AMERICAN EFFORTS TO DEVELOP AN ELECTROMAGNETIC RAILGUN LAUNCHER HAVE ACHIEVED IN THE LAST TWO YEARS ALONE WHAT DEFENSE DEPARTMENT PLANNERS HAD ONCE PREDICTED WOULD TAKE A DECADE.”

The paper lists three companies with various spacecraft/projectile designs. They cite familiar tracking methods, using infrared heat signatures and millimeter wave radar to fix fast moving targets in space.

Although Have Sting never came to be, it spawned lucrative follow up contracts. “One sponsored by the USAF called Saggitar which studied space-based EM platforms,” the paper notes, “and the other sponsored by the [Army] called Gremlin which studied ground based EM launchers.”

The paper goes on to trace some budgeting as an indicator that the effort was real—or at least real expensive. Follow on contracts for the space-based railgun project alone, paid to the Boeing Aerospace, reach as high as $20.1 million.

This money, and even more so the tens of millions being poured into ground-based EM nuke killers, pressed fast-forward on railgun research. “American efforts to develop an electromagnetic railgun launcher have achieved in the last two years alone what Defense Department planners had once predicted would take a decade,” The New York Times said in 1986.

Those advances in EM weapon research remain relevant today though that future remains uncertain. Still, the Navy has railgun aspirations that have yielded groundbreaking test speeds, and the Navy could one day launch warplanes from carriers using EM rails.

But the echo of the Have Sting program lingers in other modern methods of ground-based defense systems. Modern ICBM defense systems launch hunter-killer spacecraft, launched on rockets, that use sensors to detect warheads while they are in space, destroying them in a collision.

These “death stars”—designed in the throes of a world war, experimented with during a cold one, and refined in preparation for orbital conflict—never worked out and could be dismissed as technological dead ends. But as space becomes more militarized, the roads they paved seem to lead somewhere.

In time, they could be seen as the precursors of a new—and frightening—battlefield.