When Stress Is Bad: Forensic Structural Engineering

Determining the cause of

structural failures is the challenging discipline of forensic structural

engineering. Determination of civil and criminal liabilities drive many such

investigations, but there are also valuable lessons to be learned from these failures.

Not So Elementary, My Dear Watson

Collecting facts to recreate

the scene of a crime has been a fascinating fictional story plot long before

Sherlock Holmes became popular. In reality, the investigating detective may not

work in law enforcement but instead, work in the extremely interesting field of

forensic engineering. And the case may not necessarily involve criminal

activities although many such cases arise. Instead the investigator may simply

be determining the cause of failure in order to improve materials, designs, and

intended use of an engineered product or structure.

One of the first applications

of structural failure analysis may have been developed by the early engineers

of the Roman Empire. As the story goes, engineers who built arches were expected to stand beneath the

completed construction as the supporting formwork was removed. If the structure

held together properly, the engineer lived to begin the next project. If the

structure collapsed, the surviving engineers and apprentices presumably gained

valuable insight on how bad design, materials, workmanship, and/or overloading

affect structural performance.

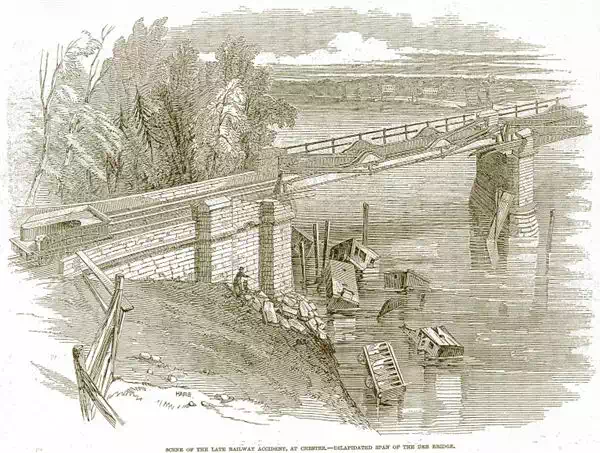

160 Years Ago

A more recent, and possibly

the first, well-documented example of complete structural failure analysis

resulted from the 1847 collapse of the Dee River railroad bridge in England. It was built using cast

iron main girders between spans with wrought iron supports. After extra ballast

had been applied to the track across the bridge as a precautionary measure

against timber fires, one of the spans collapsed under a passing train causing

injuries and fatalities.

The incident initiated a

review process which is generally followed by forensic engineers to this day:

an investigation was performed by a lead engineer who examined the site of the

failure, collected materials, performed testing and analyses, reviewed witness

statements, recreated events, and formulated a report attributing causation of

the structural failure. And like modern investigations today, the failure

analysis was not conclusive, but was able to determine probable cause. The

design was deemed defective allowing fatigue failure of a cast iron beam,

exacerbated from the weight of the extra ballast which had been applied only a

few hours prior to the collapse. The wrought iron supports did not strengthen

the structure as intended due their poor design implementation in the

structure. Testing of the materials showed cast and wrought iron was prone to

fatigue cracking failure, calling into question its use on other bridges and

structures. Finally, continued failure of bridges and other structures using cast

and wrought iron led to the development of high strength steels and other

alternative materials.

A Few Years Ago - Lesson Learned?

Forensic engineering has come

a long way since those early days. Professional associations, advanced degrees,

certifications, and consulting services abound. Vaster understanding of

material properties and usage has led to better engineering design. Dedicated

laboratories and computer simulations have become highly developed tools

to analyze material and system failures.

Tragically, however, forensic engineering is still required for failures

involving loss of life and limb.

Expert witness testimony is

commonplace to determine criminal and civil liabilities. Strategically placed

cameras and data recording systems can often capture failures as they occur,

greatly reducing the uncertainty of conflicting eyewitness reports. And bridges

still fall due to failed material and poor design, as the all too recent

collapse of the I-35W overpass in Minnesota confirmed over 160 years after the

Dee River bridge failure. Incredible as it may seem, the resulting 2008 NTSB

report attributes the collapse to inappropriate addition of covering material

dead load, in this case 2" of concrete overlays, and failed design of

supporting members, in this case undersized gusset plates.