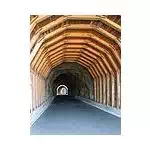

Build a Tunnel on Land and Float It into Place

The immersed tube method of

tunnel construction involves making the tunnel in segments at more convenient

locations and then bringing them to the site and immersing them to join up with

each other. It is a cost effective alternative to tunnels bored in place.

The first of these was built

in Michigan under the Detroit River in 1910. The weight of these elements is

such is that once they are sunk they would be no possibility of their ever

floating again. Each immersed tube tunnel section will have temporary bulkheads

across the ends that allow them to maintain their insides dry.

Immersed Tube Construction

Immersed tube construction of

underwater tunnels will have its elements built separately in a dry dock or

shipyard. These elements are then taken to the site where a trench has already

been made under the water to receive them. The segments are then immersed in

the water and then joined to each other to form the tunnel. Elements have

weighed as much as fifty five thousand tons and in some cases have been as long

as a football field.

The major advantage of such a

method is that it does not need to use compressed air or other techniques to

keep out the water from the tunnel as was being done in earlier construction.

There are more than 100 such tunnels constructed all over the world that have

used this technology, and some of them are kilometers long.

Procedure for construction

Tunnel elements are built in a

casting basin or fabrication yard or on a ship lift platform. It is quite the

usual thing to fabricate the outer shell of the element in steel. The section

is then floated out to sea and when roughly in position, the steel forms are

filled with concrete, which gives the tunnel body and weight. Tunnels have also

been built using only concrete walls cast in a casting yard. Once the elements

are ready, the two ends are fitted with temporary bulkheads that will not allow

water to enter. Often the weight of the element is such that separate

floatation arrangements have to be made to enable it to be shipped to the final

spot. Rubber seals are also a part of the ends of each element.

While these tunnel elements

are being made or cast, a trench is dug into the water channel where the tunnel

will finally rest. This is done by dredging. This by itself is a laborious job,

as excavated material has to be carefully removed so as not to disturb marine

life or the surrounding ecology. This may even involve rock breaking and

blasting where rocky layers are in the way of the alignment. It is also the

norm to lay foundations for the tunnel element that may involve piling and

concreting for the base.

Extremely high load-carrying

capacity floating cranes are the norm nowadays, and these are mainly available

on hire from suppliers all around the world. Once the element is in place at

the water level, it is lowered into the trench and placed against the previous

element that is already under water. Water between the bulkheads of the old and

new element is then removed which causes the rubber seals to press against each

other and close the joint.

Backfill material, obtained

from the dredged material, or sand and gravel is then placed over the tunnel

segments, permanently burying them at their final resting place.

Why Immersed Tube Is a Preferred Method of Construction

Costs for immersed tube

tunnels are considerably lower than those involved in boring a tunnel beneath the

water. The speed of construction is also greater, mainly because activities are

simultaneously carried out for almost the entire length of the tunnel. A bored

tunnel would be restricted to work and progress from two ends. There is also

very little disruption of traffic on the water channel under which it is being

laid. Boring of tunnels involves a lot of safety aspects, like dealing with

water and air pressure, which is not the case in making immersed tubes.

However, such immersed tube

tunnels are vulnerable to sabotage and shipping hazards as they are normally

quite close to the surface of the bed of the channel. There is also a problem

for waterproofing the joints, which remains a weak point. The connections have

to be designed very carefully to take care of all forces being transferred on

to them during the laying and joining process.