1958 Jersey Train Crash on a Drawbridge

On 15th September 1958, the

commuter train carrying passengers from Bay Head to Jersey Central met with a

fatal accident. The engineer ignored three warning lights and both train

locomotives tumbled off the end of an open drawbridge, dragging two of their five

cars into the waters of Newark Bay.

Freight/Passenger Train Transformed to Commuter Train

The commuter train started off

as a normal freight/passenger train, leaving Jersey City Central Station with

two GP7 locomotives pulling 18 cars that were dropped off enroute to Bay Head Junction. It arrived there on the

weekend with four passenger cars, one combine car, and the same two GP7

locomotives.

This was now the commuter

train that passengers travelling to their work in New York some 60 odd miles

away embarked in on the Monday morning.

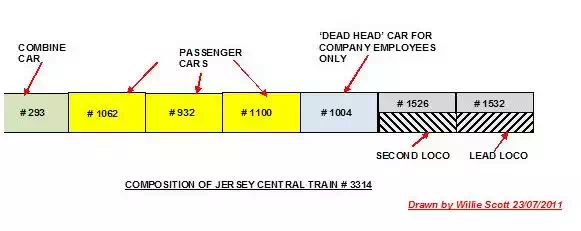

The Central Railroad of New

Jersey commuter train #3314, was composed of the following cars and locomotives;

3 passenger cars

1 Combine car: a half luggage

and half passenger car divided by partition

1 “dead head" car (reserved

for the rail company employees travelling between jobs)

Two GP7 General Motors Locos:

#1532 being the lead and having the controls; #1526 being the second loco.

A sketch of the train is shown

below. (Please click on the image to enlarge.)

The Locomotives

As noted earlier, the

locomotives pulling the ill-fated commuter train were GP7’s (commonly called

"geeps") built at the Electro-Motive

Division (EMD) of General Motors in Illinois up until 1954. A typical GP7 is

shown below.

The first loco on our

particular train was a GP7 and this contained the controls being operated by

the engineer and fireman. It was designated by the No. 1532. The second loco

was a GP7B; it had no controls and carried the No. 1526.

Both locos were of the

four-axle type and were powered by an EMD567B diesel engine of 16 cylinders and

1500 HP.

The GP7’s were a road

switcher, but were designed also as a general purpose yard switcher loco that

could also haul freight and power trains in both directions. It was very

popular with both the maintenance and train crews because of its ease of

maintenance, reliability, and its full-length catwalk.

These engines were replaced in

1954 by a higher horsepower engine: the GP9.

The Newark Bay Bridges

The first bridge across Newark

Bay was a wooden trestle single-track, center swingbridge that was 217' long. It burned down in 1889

after a schooner collided with it, setting it alight.

In 1901 a replacement bridge

was built. This was a twin-tracked drawbridge, or bascule, bridge type that

opened to about 90' on each section to let the ships through.

Due to the increase in the

popularity of rail travel, this one was superseded in 1928, being replaced this

time by a four-track vertical lift bridge designed and built by Weddell.

Vertical lift bridges were

used over rivers and bays to allow ships to pass under mainly because of cost

compared to other types of opening bridges. They also required a much smaller

counterweight, enabling stronger, heavier decks to be incorporated. This in

turn allowed heavier freight trains to traverse them. They had one distinct

disadvantage in that the tonnage of ships passing below the lifted section was

limited due to the height of the raised deck.

The Newark Bridge was 1.3

miles long having four tracks on four main horizontal lift sections of 200' and

300’. It was operated by four turrets that lifted the sections to a height of

118’. These were built from steel girders with a total weight of 44,000 tons.

It also suffered structural damage due to a ship colliding with the structure

at the waterline.

It spanned the Newark Bay

between Bayonne and Elizabeth Port, being last used in 1978. Some years later

in the 80’s it was deemed a hazard to shipping. Controversially demolished, it

was razed down to its block foundations. These large stone founds are all that

remain of the Newark Bay Draw Bridge today.

An Image of the Newark Bay

Bridge with both lift sections raised is shown below.

The Bridge Signals and Safety Systems

The safety systems were as

follows;

1. CAUTION

Signals (2)

First one at 3/4 mile from the

bridge: Red-over-Green. (Proceed with caution at medium speed; in this case 22

mph)

Second one ¼ mile from the

bridge: Yellow-over-Red. (Proceed, preparing to stop at next signal)

2. Red

Light STOP Signals (1)

One at 500’ from the bridge:

Red-over-Red-over Red.(Stop)

3. Derail

System (1)

Mechanical derail, put into

action by the bridge controller before raising the bridge. This consisted of a

mechanism similar to a set of points, except the rails directed the train truck

wheels onto the ballast and crossbeams of the track. This derail mechanism is

placed so that it should slow down and stop the train before it reached a

raised bridge; in this case 450' from the bridge. However the train was

traveling too fast for the derail to have the designed effect.

The Lead-up and After Effects of the Disaster

The Sand Captain,

a sand dredger, was approaching the bridge and as her height exceeded the 35’

clearance under the bridge, she signaled the

bridge controller for access. As she had maritime right of way, the bridge

controller Patrick Corcoran put all rail signals to caution and stop, then

opened the derailing mechanism. This was standard procedure, and interlocked

with the lifting mechanism, allowed him to lift the bridge to let the Sand

Captain pass under.

As he went outside the control

room to watch the sand dredger pass under he looked back up along the bridge

trestle, expecting to see train #3314 stopped at the last light.

Imagine his shock and horror

as he witnessed the train plunging off the rails between the concrete counter

weights and the lifting section into Newark Bay waters. It was 10.01 am

precisely.

Below the bridge only the

quick reaction of her captain averted a further disaster as he put the vessel

to emergency astern, narrowly avoiding the train’s descent to the bay. He then

made the distress signal of four long blasts on the ships horn/whistle that

brought the disaster to the attention of the local people.

The two locomotives along with

the deadhead and first passenger cars disappeared into the water. The third car

hung up on its rear trucks, and the fourth and fifth cars remained on the

bridge trestle.

Some passengers managed to

escape from the submerged cars and swam to the safety of the lower structure

foundations. Others in the suspended car also managed to swim or jump to safety

before it too fell into the bay a few hours later.

Meanwhile up in the control

room, the bridge operator had raised the alarm to his supervisor who stopped

all movement of trains toward the bridge and alerted the Coast Guard.

The Rescuers

The train was carrying around

100 passengers, and out of these 44 people lost their lives. It is certain that

more would have been lost were it not for the quick response of the Coast

Guard, who were quickly on the scene of the disaster, and to the following

civilians who also played a vital part in the rescue of survivors.

Ed McCarthy a local marina

owner who went out in his 17’ boat a number of times, filling it with survivors.

Local boys out on a fishing

trip managed to pull some of the survivors out of the water. One of the boys

known as Young Sellers was injured himself in the operation.

The rescue was over in under

an hour when anyone who was going to be saved had been saved.

The Investigation

There were several

investigations into the 1958 Jersey train crash.

They all concluded that the

train driver was to blame for ignoring all the signals and not slowing down or

stopping the train. This was thought to have been caused by a heart attack,

although why the fireman took no action remains a mystery.

The main recommendation to

come out of it was to fit a "deadman control"

to the cab of the locomotives. The railway company was ordered to comply with

this recommendation and subsequently fitted these to all their locomotives.

Author's

Notes

Both inquests blamed the

engineer for the accident, citing a medical condition such as a heart attack as

the main cause. Whilst researching this article, I questioned what the fireman

was doing when the train passed the caution and stop signals without slowing

down. One source believed he could have gone into the 2nd loco to adjust

something such as the heating to the passenger cars, but would he have done so

at such a crucial section of the track?

Indeed another source quoted

that the train's "emergency stop" had been operated several seconds

before the train plunged over the open drawbridge, so he may have been out of

the main cab, returning in time to operate this or, maybe the engineer came to

again; we will never know, but we should learn from it.

In European railway systems,

some have red stop signals that are radio controlled so, if a train passes a

red, the radio signal automatically operates the train brakes. Maybe this is a

modern system and could not have been applied to train #3314.

Finally, this accident proved

that although there were two men in the cab; there are occasions when one man

leaves the loco; so it would have been prudent to have a deadman control. This can be a floor pedal that is

kept depressed by the engineer’s foot, if for any reason he moves his foot off

the pedal; the brakes are automatically applied. It can also be incorporated

into the main speed controller, with the same principles. Is this not a

fundamental safety precaution, even with two men in the cab?

But sure, isn’t hind sight a

great thing!