A Flying Buttress Never Leaves the Ground

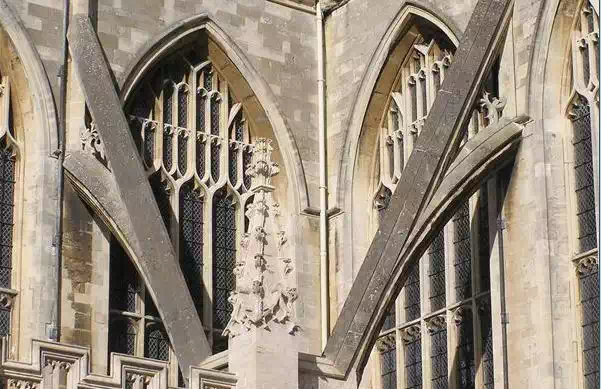

A flying buttress may sound

like military aircraft, but actually is a structural stonework support

popularized during the Gothic era. By transferring lateral forces of ceilings

and tall walls through an arch to massive columns located externally, larger interior

open spaces could be realized.

Arc-Boutant Is Not Served With A Latte

A simple buttress is a form of

external support for walls, typically an external column placed in contact with

the wall throughout its entire height. Placing the column some distance away

from the wall, and using a half-arch to connect the top of the column with the

wall/ceiling intersection, gives a structurally graceful yet lightweight

support to the wall. To the casual observer the column and arch combination appears to soar or

“fly" up to the wall, presumably giving the flying buttress its name. The

French term arc-boutant is probably a more

accurate description, roughly meaning to “thrust through the arch.“ Several such structures could be placed in series

with one another, multiplying the soaring effect while enabling even taller

structures and larger open spaces.

The exact origin of the flying

buttress is less than clear. The desire to safely and dramatically enclose

large interior spaces has been a goal of architectural design for many

centuries, typically for religious purposes. Mayan temples incorporated stone

vaults in the form of an inverted V, with horizontally placed wooden collar

ties across the interior space for support. Early Roman and later Byzantine

engineers utilized buttresses in their stonework but masked or hid the supports

from view. It wasn’t until the era of Gothic architecture that these structural

elements became desirable decorative features in cathedrals and churches of the

time. Not only did they lend a dramatic, spiritual effect to a structure, but

they also enabled architects to incorporate windows, doors, and other openings

into an otherwise heavy, load bearing wall.

Tall Ceilings and Stained Glass

It is the load transferring

capability of the flying buttress that made it so successful in Gothic Europe.

Stonework created solid, safe, and long lasting structures when properly

executed. But it was also very massive and costly to construct. Stonework is so

heavy that the simple masonry building techniques of the period could not

create tall, thin walls without fear of the structure tilting, leaning, or

otherwise collapsing on the inhabitants. Attempting to incorporate a ceiling

across a large span put additional compressive and lateral stresses near the

top of an already unstable structure. Creating window and door openings

presented further structural challenges, as headers were limited in size again

by the weight of the stone materials. By utilizing the principle of “thrust

through the arch", the stability of tall, load bearing stone walls was

greatly increased without requiring incorporation of massive individual stones

into the wall. The required mass could now be placed into the external pillar

support of the buttress, away from the interior vaults. Less load bearing on

the wall also allowed placement of more windows and doors without compromising

structural integrity. Some examples of Gothic structures utilize 70% or more of

the available wall space for doors and stained glass windows, an astonishing

figure for stonework at the time.

Replaced but Not Forgotten

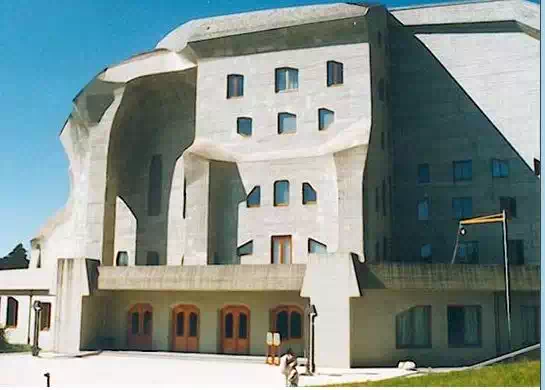

The development of other

structural materials such as iron, steel, and concrete dictated the decline in

popularity of the flying buttress. Entire walls can now be made of glass without the need for external supports,

and skyscrapers have become all but common. However, even though the structural

need for these visual supports has all but vanished, the architectural soaring

appeal can still be found in select modern structural design such as facades

and retaining walls.