STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT: SUCCESS OR FAILURE INTRODUCTION

Here we would be examining the research evidences of both planning and the success or failure of various company strategies. Here we will provide a synthesis of the early research into planning success, and will also show that not all organisations that claim to apply strategic management are doing it well. Recent research into the success and failure of certain common strategic moves will be examined. And we will conclude with a list of common areas of weakness which are found in many organisations, and where careful attention would improve the quality of strategic decisions.

It is a fact that many companies throughout the world practise some form of strategic management and we should also accept that organisations may be dedicated to strategic management, and still take the wrong decisions. We will examine some of the evidences of the benefits of strategic management, and also to look at some of the things that strategic management should have avoided, but which have still happened. The evidence needs to be looked at in two sections. The first will cover the earlier studies of whether formal approaches to planning added value to organisations.

Planning Does pay :

Unfortunately, many of the benefits of a planning process are difficult to

prove in absolute terms. This is because once planning is introduced, the

company changes, and it is never possible to compare what has happened with

what would have happened under different circumstances.

Advantages of planning :

The advantages of planning include the opportunity to:

· Conduct a SWOT analysis of the business to determine its leadership needs now and in the coming years

· Develop a strategic Leadership Human Resource Plan that includes comprehensive position descriptions, needs analysis and plans to bridge the gaps

· Build relationships with and carefully study the performance and behavior of successors over a long period of time

· Provide a sense of direction, stability and expectations for all key stakeholders: employees, customers, shareholders and vendors

· Retain a critically important employee who might otherwise leave if not formally recognized as the successor

Disadvantges of planning :

It’s difficult to think that there might be disadvantages to succession

planning but here are some things to consider:

· Appointing the wrong person can lead to a variety of problems that result in poorer company performance and turnover

· Pulling the trigger too quickly to appoint someone only to have a better candidate appear later on

· Engaging in succession planning when the business is immature may lead to erroneous conclusions about leadership needs

· A poorly conducted succession planning process will lead to poor decisions, disharmony and ultimately poor company performance as well

In addition, there is a major problem in identifying the costs of planning. Real benefit can only come if the additional profit earned exceeds the additional costs of planning. Quite apart from the conceptual problem of specifically separating the benefits of planning from those of other causes, it is almost impossible to identify costs. It may be easy to isolate the costs of any specialist planning staff, but this is only a part. It is very difficult to estimate the cost of the participation of other managers in the process – and an overwhelming task to try to see how the cost of their participation differs from what it would be under some other style of management. Under any circumstances managers will spend some time on planning: how much more (or less) they will spend where a company has a formal planning process can probably never be computed in meaningful terms.

One of the first serious attempts to survey planning in the UK was undertaken by Denning and Lehr in 1967. It was found that 25 per cent of companies from The Times top 300 were practising some form of corporate planning. The survey showed, at that time, that it was only in seven industry groups that 25 per cent or more of the companies in those groups were definitely undertaking corporate planning. Across the Atlantic, evidence that planning was acceptable was provided bythe 1966 National Industrial Conference Board Survey of Business Opinions and Experience. This revealed that over 90 per cent of manufacturers sampled practised some form of formal corporate planning.

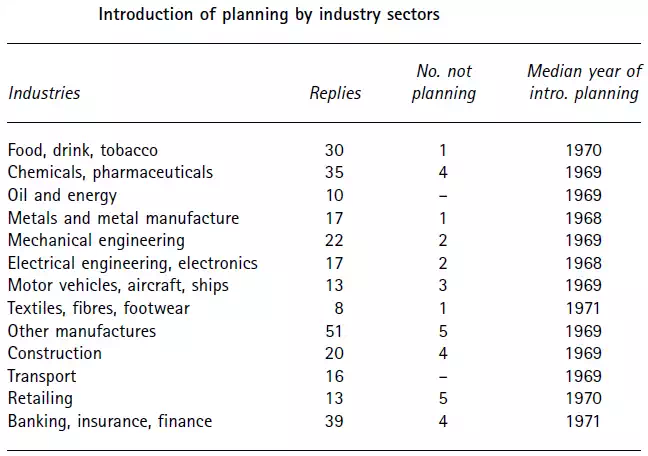

Similar studies in certain other countries have suggested that around 80 per cent of companies sampled have some kind of wide long-range plan. The Dutch survey suggested that Holland lagged the USA and the UK by about five years. Denning’s and Lehr’s and subsequent studies in both the UK and the USA proved that there were companies who had moved into corporate planning as early as the 1950s. Not all the evidence is straightforward. Another survey by Kempner and Hewkins in 1968 found that few British companies had implemented corporate planning. A membership survey carried out by the Society for Long Range Planning in1974 gave further confirmation of the differences of timing in the introduction of planning by type of industry. Table illustrates some of the findings.

The median year of introduction would, of course, move if the survey were to be repeated today and if new firms had commenced planning. (Those not planning were organisations who had employees who belong to the Society, and the overall total not planning in the industry would be higher.) In the mid-1960s finding companies that planned in some industries (for example, banking) was rather like seeking needles in haystacks. The fact that many companies were undertaking planning is one thing. Whether or not they were satisfied with what they were getting out of it was another, but it is worth mentioning that he found many misconceptions about what long-range planning really was. A further general conclusion was that in most of the companies, planning was still in an evolutionary stage. And the results achieved are affected by the skill with which the process is applied.

In general, the conclusions of the survey evidence to this point was that an increasing number of companies were introducing this system of management, but many had a long way to go before they could be classified as effective planners. Since the mid-1970s, planning has become established in most organisations of any size, in most major countries. However, there has also been almost continuous research that has regularly thrown up the feeling that planning has not worked as well as it should have in many organisations.

The Society for Long Range Planning study mentioned earlier provided fascinating evidence of what planning companies did and did not do. While most practised formal financial planning, forecast external events and reviewed performance against plan, only 25 per cent undertook contingency planning, 36 per cent diversification planning and 22 per cent divestment planning. Equally surprising, only 45 per cent undertook formal organisation planning and 53 percent formal manpower planning.

Denning and Lehr subjected their survey results to a detailed statistical evaluation of the planning companies when compared with the non-planners: If the introduction of formal long-range planning is, in fact, a managerial response to critical strategic or co-ordinative needs, one would expect evidence to that effect in the observed pattern of incidence. Vital strategic needs exist in situations of high financial risk or opportunity, whereas coordinative needs increase with the complexity of organizations. The following key parameters were selected for the analysis:Financial Risk/Opportunity – Rate of technological change

Growth and variability of

turnover/profits

Complexity – Size

Type of organization structure

Degree of vertical integration.

Each variable was analysed separately and the data were then subjected to a multivariate analysis. The main findings were that there was a strong positive correlation between the introduction of long-range planning and companies with a high rate of technological change and a clear positive relationship between planning and capital intensity. Growth and variability of turnover were found to affect the introduction of planning only marginally.Only two of the ‘complexity’ factors could be measured, both size and organisational complexity having a strong relationship with the introduction of planning.

Two additional facts of interest emerging from the study were variation in the way that companies tackled the planning task and the higher proportion of subsidiaries of foreign companies who were doing corporate planning. While British companies included 23 per cent known ‘planners’, the foreign subsidiaries had 61 per cent of their number engaged in this activity. It is possible to draw two alternative hypotheses from the Denning/Lehr survey:

1. The complex, high-capital, technological companies are the companies

most likely to benefit from corporate planning; or

1. That they are likely to perceive the need for planning before.

Certainly a planning process which does not produce clear objectives and logically evaluated plans will have little value, and the efficiency of the system is a very important factor in its success. Certainly, the assessment of strengths and weaknesses may lead to immediate profit improvement opportunities, the coordinative ability of planning may bring an immediate improvement in communication, or planning may be the factor which leads to an organisational change.

In the third group of reasons there is a genuine effort to identify the real and tangible results of corporate planning. Such writers usually point to sustained growth and profitability, clarity of purpose, better communication, identification of additional opportunities, coordination, and better decision making.