CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY (CSR)

Someone once famously said that “the business of business is business”. That is no longer how an increasingly numerous and vocal group of people see things. Or rather, they have concluded that if the business of business is business, the parameters of what constitutes good business need to be redefined in the modern world. Demand for corporate social responsibility (CSR) has developed largely in response to the real or perceived failure of legislation, regulation and enforcement to control and regulate the impact of company activities on people and the environment. It has also arisen alongside the scaling back of command and control measures by many governments around the world.

As competition increases amongst companies, workers fear that there will be a race to the bottom as far as wages and conditions are concerned. This fear has some basis, in that labour-intensive industries – other things being equal – tend to locate where labour is cheapest. But if competition has increased, so has scrutiny of companies. It is not only the State that polices companies in the modern world; there is also an active and informed non-governmental organizations (NGO) community which increasingly performs this function. Trade unions cannot be considered NGOsin the normally understood sense of the term, because of the vested interests of their members in the success of companies in which they work.

Nevertheless, there is much that is familiar to trade unions in the CSR debate. Social wages, decent working hours, basic health and safety standards, abolition of child labour and protection against discrimination are just some of the trade union issues that fall within any reasonable definition of CSR. However, CSR also embraces a range of topics that have until recently not been part of the traditional trade union agenda – or only peripherally a part of it. CSR is today typically associated with the concept of sustainable development or “sustainability”. Trade unions are, in response, developing their sustainability agendas and linking these with improved and extended CSR.One of the most significant developments in this regard has been the development and signing of global agreements between a number of Global Union Federations (GUFs) – including the ICEM – and multinational corporations. Whilst these agreements help to promote CSR, they do not on their own guarantee it.

They are, typically, framework agreements that set the general tone for corporate behaviour and relations between the corporation, its workers and their unions. They are therefore more properly to be considered as enabling mechanisms. Global agreements highlight the importance of, and need to be based on, genuine transparency, honesty, cooperation, participation and conflict identification and resolution – vital elements of any CSR commitment. Signatories to such agreements recognize that there are two sides to them – the commitments and obligations of the company on the one hand and those of the relevant GUF on the other. It is a sine quanon for any agreement to be effective that both sides to the agreement must derive benefit from it.

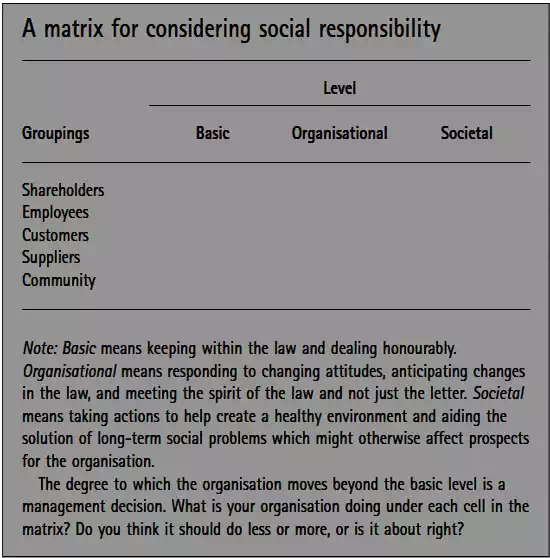

Hargreaves and Dauman suggest that there are three levels of distinct but interrelated areas of social responsibility: Basic responsibilities generated by the existence of the organisation. This, they define, includes the need to keep within the letter of the law, to observe formal codes of conduct, to safeguard basic shareholder and employee interests, andto deal honourably with customers, suppliers and creditors. Organisational responsibilities which meet the changing needs of stakeholders , respond to changing attitudes, observes the spirit of the law rather than just the letter, and anticipates changes in legislation. Societal responsibilities, which help create a healthy environment in which the organisation can prosper, and help to solve key social problems which if not dealt with could affect the long-term prospects of the organisation.

While most people would argue strongly that every organisation should behave in an ethical and moral way, it is possible to see from the above classification that it is possible to be ethical and moral at each of the three levels. So because an organisation chooses to restrain itself to the basic level, it does not mean that it lacks integrity. Of course, the cynics have argued that the term business ethics is an oxymoron, and certainly some businesses fall far short of what is generally accepted moral and ethical behaviour. As an organisation moves from the level of basic responsibility to embrace all three levels, it moves into situations of conflict. Jackall4 observes:

Even more difficult is fashioning some working consensus about the meaning of ‘corporate social responsibility’, a consensus that includes top management, external publics that top management is trying to appease, and middle management that must implement a policy. Here the precariousness of ideological bridges between the interests of a corporation, individual managers, and the public are most apparent Of the five groups to whom the company has obligations the one which would cause least surprise is the duty owed to shareholders. In general terms we may describe this as a duty to earn the shareholder an adequate return on investment and to preserve assets for the future. Dealing in detail with corporate objectives, defines this generalisation in more detail and in a way which can be meaningly quantified for planning purposes.

For the present purpose the general concept of profit is sufficient. Other duties to shareholders may be harder to define and cause more differences of opinion – consider, for instance, the paucity of information given to shareholders by many companies: despite improvements by some, many annual company reports are designed to conceal more than they reveal. What perhaps is of more significance to a study of business philosophy and ethics is the lack of influence that shareholders have on the day-to-day management of the companies they own. The Financial Timesreports Galbraith as arguing that: Some 40 per cent of the Gross National Product of the U.S. is controlled by 2000 giant corporations in manufacturing, merchandising, transport and the utilities.

If the great state corporations are included in the ‘technostructure’, a similar proportion of the national product in Italy, France and Britain is controlled by an equally small number of concerns. Their ambitions may not coincide with those of society as a whole. Shareholders, Galbraith maintains, no longer have much influence on the day-to-day management of corporations. As a result managers have become more concerned with growth than with earnings. So long as a corporation makes a reasonable rate of return its managers have virtually complete power and their brief concern is to enlarge the scope of their operations and increase the size of their company.