NASA spacecraft gets a look at one of the strangest places in the solar system

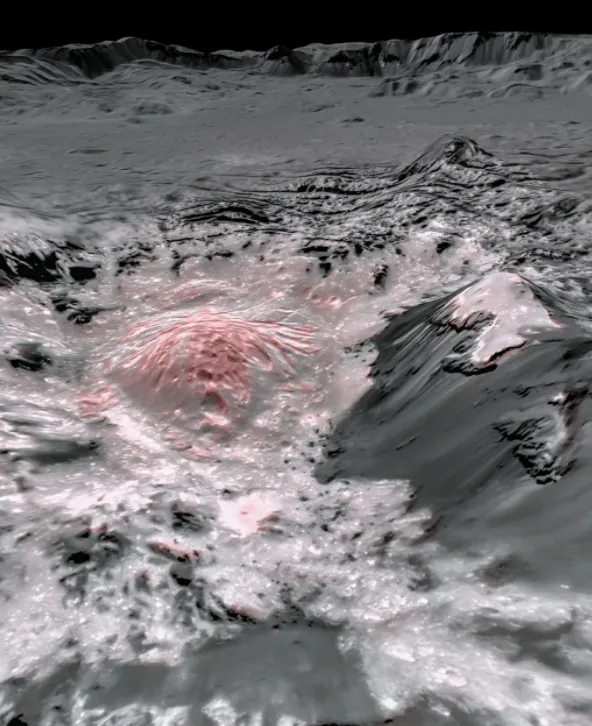

An animation stitches together images showing briny deposits, colored in reddish, splaying across Occator Crater on Ceres, as seen by NASA's Dawn mission.

For a few months in 2018, as NASA's Dawn spacecraft used up its last drops of fuel, it gave scientists an incredibly detailed look at one of the strangest places in the solar system: Occator Crater.

That's the name of a massive impact site on the dwarf planet Ceres, tucked away in the asteroid belt. In the mission's last months, Dawn flew just 22 miles (35 kilometers) above the dwarf planet's surface and focused its energies on Occator Crater. Earlier observations from the mission had suggested that some sort of geological activity was bringing saltwater to the surface, and scientists wanted a closer look.

Now, initial analysis of those final months of science suggest that Ceres may have been active much more recently than scientists had dared to imagine, according to an article summarizing seven different research papers published Monday (Aug. 10) in the journals Nature Communications, Nature Geoscience and Nature Astronomy.

"Dawn accomplished far more than we hoped when it embarked on its extraordinary extraterrestrial expedition," Mission Director Marc Rayman of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California said in a NASA statement. "These exciting new discoveries from the end of its long and productive mission are a wonderful tribute to this remarkable interplanetary explorer."

The new research papers focus on a host of different intriguing findings about Occator Crater, which is about 22 million years old and about 57 miles across (92 km), as well as about Ceres more generally.

One of the new papers, for example, constructs a detailed timeline of geological events at the crater, hypothesizing that cryovolcanism began just 9 million years ago and continued for several million years. A series of bright deposits formed over that time from brine seeping out from Ceres' mantle through the upper layer of rock, with activity continuing as recently as a million years ago.

![]()

An image built on data gathered by NASA's Dawn spacecraft shows briny deposits colored reddish against Occator Crater on Ceres

And this volcanism, the authors argue, is unlike any other in the solar system, since it occurs on a relatively small object that isn't subject to the gravitational tugs experienced by places like Jupiter's ultra-volcanic moon Io.

Another paper identifies a specific form of salt found so far only on Earth and now on Ceres that is particularly short-lived, on the scale of centuries, according to a statement. The combination suggests that the brines that deposited them on the surface must have done so very recently and perhaps continue to move through the asteroid today. These salts could also solve the puzzle of what's keeping Ceres relatively warm without gravitational tugging and could be responsible for maintaining pockets of liquid within the asteroid.

And the impact that created Occator Crater itself may have brought enough heat to the dwarf planet to trigger the brine seepage that left bright deposits at the surface by forcing the brine through older cracks in the rock.

![]()

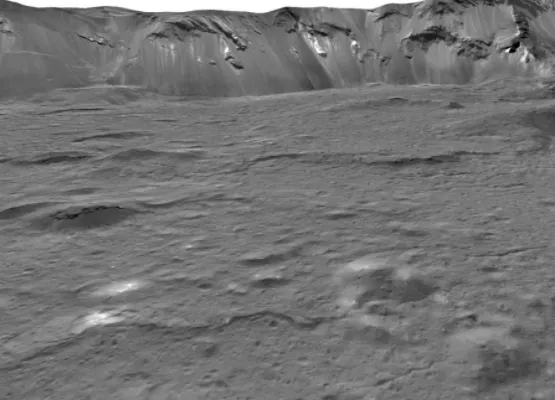

Hills and mounds on the floor of Occator Crater on Ceres as seen by NASA's Dawn mission.

Another paper attempts to identify where the brine in different patches of the crater came from, suggesting that certain areas come from water in the melted subsurface pool created by the impact itself and some from an older and deeper, more global reservoir on Ceres.

Other papers in the new batch of research analyze how Ceres' crust differs in different locations, how the mounds and hills inside the crater may have formed and how the salty deposits compare to activity on the moon and on Mars.