Biological significance

The importance of carbohydrates to living things can hardly be overemphasized. The energy stores of most animals and plants are both carbohydrate and lipid in nature; carbohydrates are generally available as an immediate energy source, whereas lipids act as a long-term energy resource and tend to be utilized at a slower rate. Glucose, the prevalent uncombined, or free, sugar circulating in the blood of higher animals, is essential to cell function. The proper regulation of glucose metabolism is of paramount importance to survival.

The ability of ruminants, such as cattle, sheep, and goats, to convert the polysaccharides present in grass and similar feeds into proteinprovides a major source of protein for humans. A number of medically important antibiotics, such as streptomycin, are carbohydrate derivatives. The cellulose in plants is used to manufacture paper, wood for construction, and fabrics.

Role in the biosphere

The essential process in the biosphere, the portion of Earth in which life can occur, that has permitted the evolution of life as it now exists is the conversion by green plants of carbon dioxide from the atmosphereinto carbohydrates, using light energy from the Sun. This process, called photosynthesis, results in both the release of oxygen gas into the atmosphere and the transformation of light energy into the chemical energy of carbohydrates. The energy stored by plants during the formation of carbohydrates is used by animals to carry out mechanical work and to perform biosynthetic activities.

photosynthesis in glucose and oxygen productionThe role of photosynthesis in glucose and oxygen production in plants.

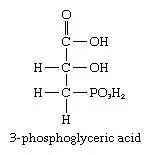

During photosynthesis, an immediate phosphorous-containing product known as 3-phosphoglyceric acid is formed.

This compound then is transformed into cell wall components such as cellulose, varying amounts of sucrose, and starch—depending on the plant type—and a wide variety of polysaccharides, other than cellulose and starch, that function as essential structural components. For a detailed discussion of the process of photosynthesis, seephotosynthesis.

Role in human nutrition

The total caloric, or energy, requirement for an individual depends on age, occupation, and other factors but generally ranges between 2,000 and 4,000 calories per 24-hour period (one calorie, as this term is used in nutrition, is the amount of heat necessary to raise the temperature of 1,000 grams of water from 15 to 16 °C [59 to 61 °F]; in other contextsthis amount of heat is called the kilocalorie). Carbohydrate that can be used by humans produces four calories per gram as opposed to nine calories per gram of fat and four per gram of protein. In areas of the world where nutrition is marginal, a high proportion (approximately one to two pounds) of an individual’s daily energy requirement may be supplied by carbohydrate, with most of the remainder coming from a variety of fat sources. Although carbohydrates may compose as much as 80 percent of the total caloric intake in the human diet, for a given diet, the proportion of starch to total carbohydrate is quite variable, depending upon the prevailing customs. In East Asia and in areas of Africa, for example, where rice or tubers such as manioc provide a major food source, starch may account for as much as 80 percent of the total carbohydrate intake. In a typical Western diet, 33 to 50 percent of the caloric intake is in the form of carbohydrate. Approximately half (i.e., 17 to 25 percent) is represented by starch; another third by table sugar(sucrose) and milk sugar (lactose); and smaller percentages by monosaccharides such as glucose and fructose, which are common in fruits, honey, syrups, and certain vegetables such as artichokes, onions, and sugar beets. The small remainder consists of bulk, or indigestible carbohydrate, which comprises primarily the cellulosic outer covering of seeds and the stalks and leaves of vegetables. (See also nutrition.)

Role in energy storage

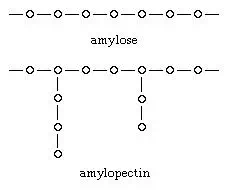

Starches, the major plant-energy-reserve polysaccharides used by humans, are stored in plants in the form of nearly spherical granules that vary in diameter from about three to 100 micrometres (about 0.0001 to 0.004 inch). Most plant starches consist of a mixture of two components: amylose and amylopectin. The glucose molecules composing amylose have a straight-chain, or linear, structure. Amylopectin has a branched-chain structure and is a somewhat more compact molecule. Several thousand glucose units may be present in a single starch molecule. (In the diagram, each small circle represents one glucose molecule.)

In addition to granules, many plants have large numbers of specialized cells, called parenchymatous cells, the principal function of which is the storage of starch; examples of plants with these cells include root vegetables and tubers. The starch content of plants varies considerably; the highest concentrations are found in seeds and in cereal grains, which contain up to 80 percent of their total carbohydrate as starch. The amylose and amylopectin components of starch occur in variable proportions; most plant species store approximately 25 percent of their starch as amylose and 75 percent as amylopectin. This proportion can be altered, however, by selective-breeding techniques, and some varieties of corn have been developed that produce up to 70 percent of their starch as amylose, which is more easily digested by humans than is amylopectin.

In addition to the starches, some plants (e.g., the Jerusalem artichokeand the leaves of certain grasses, particularly rye grass) form storage polysaccharides composed of fructose units rather than glucose. Although the fructose polysaccharides can be broken down and used to prepare syrups, they cannot be digested by higher animals. Starches are not formed by animals; instead, they form a closely related polysaccharide, glycogen. Virtually all vertebrate and invertebrate animal cells, as well as those of numerous fungi and protozoans, contain some glycogen; particularly high concentrations of this substance are found in the liver and muscle cells of higher animals. The overall structure of glycogen, which is a highly branched molecule consisting of glucose units, has a superficial resemblance to that of the amylopectin component of starch, although the structural details of glycogen are significantly different. Under conditions of stress or muscular activity in animals, glycogen is rapidly broken down to glucose, which is subsequently used as an energy source. In this manner, glycogen acts as an immediate carbohydrate reserve. Furthermore, the amount of glycogen present at any given time, especially in the liver, directly reflects an animal’s nutritional state. When adequate food supplies are available, both glycogen and fat reserves of the body increase, but when food supplies decrease or when the food intake falls below the minimum energy requirements, the glycogen reserves are depleted quite rapidly, while those of fat are used at a slower rate.

Role in plant and animal structure

Whereas starches and glycogen represent the major reserve polysaccharides of living things, most of the carbohydrate found in nature occurs as structural components in the cell walls of plants. Carbohydrates in plant cell walls generally consist of several distinct layers, one of which contains a higher concentration of cellulose than the others. The physical and chemical properties of cellulose are strikingly different from those of the amylose component of starch. In most plants, the cell wall is about 0.5 micrometre thick and contains a mixture of cellulose, pentose-containing polysaccharides (pentosans), and an inert (chemically unreactive) plastic-like material called lignin. The amounts of cellulose and pentosan may vary; most plants contain between 40 and 60 percent cellulose, although higher amounts are present in the cotton fibre. Polysaccharides also function as major structural components in animals. Chitin, which is similar to cellulose, is found in insects and other arthropods. Other complex polysaccharides predominate in the structural tissues of higher animals.

Structural Arrangements And Properties

Stereoisomerism

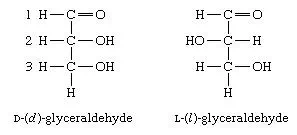

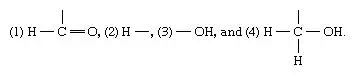

Studies by German chemist Emil Fischer in the late 19th century showed that carbohydrates, such as fructose and glucose, with the same molecular formulas but with different structural arrangements and properties (i.e., isomers) can be formed by relatively simple variations of their spatial, or geometric, arrangements. This type of isomerism, which is called stereoisomerism, exists in all biological systems. Among carbohydrates, the simplest example is provided by the three-carbon aldose sugar glyceraldehyde. There is no way by which the structures of the two isomers of glyceraldehyde, which can be distinguished by the so-called Fischer projection formulas, can be made identical, excluding breaking and reforming the linkages, or bonds, of the hydrogen (―H) and hydroxyl (―OH) groups attached to the carbon at position 2. The isomers are, in fact, mirror images akin to right and left hands; the term enantiomorphism is frequently employed for such isomerism. The chemical and physical properties of enantiomers are identical except for the property of optical rotation.

Optical rotation is the rotation of the plane of polarized light. Polarizedlight is light that has been separated into two beams that vibrate at right angles to each other; solutions of substances that rotate the plane of polarization are said to be optically active, and the degree of rotation is called the optical rotation of the solution. In the case of the isomers of glyceraldehyde, the magnitudes of the optical rotation are the same, but the direction in which the light is rotated—generally designated as plus, or d for dextrorotatory (to the right), or as minus, or l for levorotatory (to the left)—is opposite; i.e., a solution of D-(d)-glyceraldehyde causes the plane of polarized light to rotate to the right, and a solution of L-(l)-glyceraldehyde rotates the plane of polarized light to the left. Fischer projection formulas for the two isomers of glyceraldehyde are given below.

Configuration

Molecules, such as the isomers of glyceraldehyde—the atoms of which can have different structural arrangements—are known as asymmetrical molecules. The number of possible structural arrangements for an asymmetrical molecule depends on the number of centres of asymmetry; i.e., for n (any given number of) centres of asymmetry, 2n different isomers of a molecule are possible. An asymmetrical centre in the case of carbon is defined as a carbon atomto which four different groups are attached. In the three-carbon aldose sugar, glyceraldehyde, the asymmetrical centre is located at the central carbon atom.

The position of the hydroxyl group (―OH) attached to the central carbon atom—i.e., whether ―OH projects from the left or the right—determines whether the molecule rotates the plane of polarized light to the left or to the right. Since glyceraldehyde has one asymmetrical centre, n is one in the relationship 2n, and there thus are two possible glyceraldehyde isomers. Sugars containing four carbon atoms have two asymmetrical centres; hence, there are four possible isomers (22). Similarly, sugars with five carbon atoms have three asymmetrical centres and thus have eight possible isomers (23). Keto sugars have one less asymmetrical centre for a given number of carbon atoms than do aldehyde sugars.

A convention of nomenclature, devised in 1906, states that the form of glyceraldehyde whose asymmetrical carbon atom has a hydroxyl group projecting to the right is designated as of the D-configuration; that form, whose asymmetrical carbon atom has a hydroxyl group projecting to the left, is designated as L. All sugars that can be derived from D-glyceraldehyde—i.e., hydroxyl group attached to the asymmetrical carbon atom most remote from the aldehyde or keto end of the molecule projects to the right—are said to be of the D-configuration; those sugars derived from L-glyceraldehyde are said to be of the L-configuration.

![Carbohydrates. sugars containing an "aldehydo group [formula] of the D-configuration."](28_files/image006.webp)

|

common name |

component sugars |

linkages |

sources |

|

*The linkage joins carbon atom 1 (in the β configuration) of one glucose molecule and carbon atom 4 of the second glucose molecule; the linkage may also be abbreviated β-1, 4. |

|||

|

**Note that raffinose and stachyose are galactosyl sucroses. |

|||

|

cellobiose |

glucose, glucose |

β1 → 4* |

hydrolysis of cellulose |

|

gentiobiose |

glucose, glucose |

β1 → 6 |

plant glycosides, amygdalin |

|

isomaltose |

glucose, glucose |

α1 → 6 |

hydrolysis of glycogen, amylopectin |

|

raffinose** |

galactose, glucose, fructose |

α1 → 6, α1 → 2 |

sugarcane, beets, seeds |

|

stachyose** |

galactose, galactose, glucose, fructose |

α1 → 6, α1 → 6, α1 → 2 |

soybeans, jasmine, twigs, lentils |

|

Representative disaccharides and oligosaccharides |

|||

The configurational notation D or L is independent of the sign of the optical rotation of a sugar in solution. It is common, therefore, to designate both, as, for example, D-(l)-fructose or D-(d)-glucose; i.e., both have a D-configuration at the centre of asymmetry most remote from the aldehyde end (in glucose) or keto end (in fructose) of the molecule, but fructose is levorotatory and glucose is dextrorotatory—hence the latter has been given the alternative name dextrose. Although the initial assignments of configuration for the glyceraldehydes were made on purely arbitrary grounds, studies that were carried out nearly half a century later established them as correct in an absolute spatial sense. In biological systems, only the D or L form may be utilized.

When more than one asymmetrical centre is present in a molecule, as is the case with sugars having four or more carbon atoms, a series of DLpairs exists, and they are functionally, physically, and chemically distinct. Thus, although D-xylose and D-lyxose both have five carbon atoms and are of the D-configuration, the spatial arrangement of the asymmetrical centres (at carbon atoms 2, 3, and 4) is such that they are not mirror images.