Electric dipole moment in the quantum world

The story of EDM, however, is very different in the quantum world. There the vacuum around an electron is not empty and still. Rather it is populated by various subatomic particles zapping into virtual existence for short periods of time.

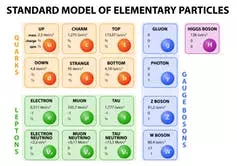

The Standard Model of particle physics has correctly predicted all of these particles. If the ACME experiment discovered that the electron had an EDM, it would suggest there were other particles that had not yet been discovered.Designua/Shutterstock.com

These virtual particles form a “cloud” around an electron. If we shine light onto the electron, some of the light could bounce off the virtual particles in the cloud instead of the electron itself.

This would change the numerical values of the electron’s charge and magnetic and electric dipole moments. Performing very accurate measurements of those quantum properties would tell us how these elusive virtual particles behave when they interact with the electron and if they alter the electron’s EDM.

Most intriguing, among those virtual particles there could be new, unknown species of particles that we have not yet encountered. To see their effect on the electron’s electric dipole moment, we need to compare the result of the measurement to theoretical predictions of the size of the EDM calculated in the currently accepted theory of the Universe, the Standard Model.

So far, the Standard Model accurately described all laboratory measurements that have ever been performed. Yet, it is unable to address many of the most fundamental questions, such as why matter dominates over antimatter throughout the universe. The Standard Model makes a prediction for the electron’s EDM too: it requires it to be so small that ACME would have had no chance of measuring it. But what would have happened if ACME actually detected a non-zero value for the electric dipole moment of the electron?

View of the Large Hadron Collider in

its tunnel near Geneva, Switzerland. In the LHC two counter-rotating beams of

protons are accelerated and forced to collide, generating various particles. AP Photo/KEYSTONE/Martial Trezzini

View of the Large Hadron Collider in

its tunnel near Geneva, Switzerland. In the LHC two counter-rotating beams of

protons are accelerated and forced to collide, generating various particles. AP Photo/KEYSTONE/Martial Trezzini

Patching the holes in the Standard Model

Theoretical models have been proposed that fix shortcomings of the Standard Model, predicting the existence of new heavy particles. These models may fill in the gaps in our understanding of the universe. To verify such models we need to prove the existence of those new heavy particles. This could be done through large experiments, such as those at the international Large Hadron Collider (LHC) by directly producing new particles in high-energy collisions.

Alternatively, we could see how those new particles alter the charge distribution in the “cloud” and their effect on electron’s EDM. Thus, unambiguous observation of electron’s dipole moment in ACME experiment would prove that new particles are in fact present. That was the goal of the ACME experiment.

This is the reason why a recent article in Nature about the electron caught my attention. Theorists like myself use the results of the measurements of electron’s EDM – along with other measurements of properties of other elementary particles – to help to identify the new particles and make predictions of how they can be better studied. This is done to clarify the role of such particles in our current understanding of the universe.

What should be done to measure the electric dipole moment? We need to find a source of very strong electric field to test an electron’s reaction. One possible source of such fields can be found inside molecules such as thorium monoxide. This is the molecule that ACME used in their experiment. Shining carefully tuned lasers at these molecules, a reading of an electron’s electric dipole moment could be obtained, provided it is not too small.

However, as it turned out, it is. Physicists of the ACME collaboration did not observe the electric dipole moment of an electron – which suggests that its value is too small for their experimental apparatus to detect. This fact has important implications for our understanding of what we could expect from the Large Hadron Collider experiments in the future.

Interestingly, the fact that the ACME collaboration did not observe an EDM actually rules out the existence of heavy new particles that could have been easiest to detect at the LHC. This is a remarkable result for a tabletop-sized experiment that affects both how we would plan direct searches for new particles at the giant Large Hadron Collider, and how we construct theories that describe nature. It is quite amazing that studying something as small as an electron could tell us a lot about the universe.