PRINCIPLES OF PREVENTION: SAFETY INFORMATION

Sources of Safety Information

Manufacturers and employers throughout the world provide a vast amount of safety information to workers, both to encourage safe behaviour and to discourage unsafe behaviour. These sources of safety information include, among others, regulations, codes and standards, industry practices, training courses, Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDSs), written procedures, safety signs, product labels and instruction manuals. Information provided by each of these sources varies in its behavioural objectives, intended audience, content, level of detail, format and mode of presentation. Each source may also design its information so as to be relevant to the different stages of task performance within a potential accident sequence.

Four Stages of the Accident Sequence

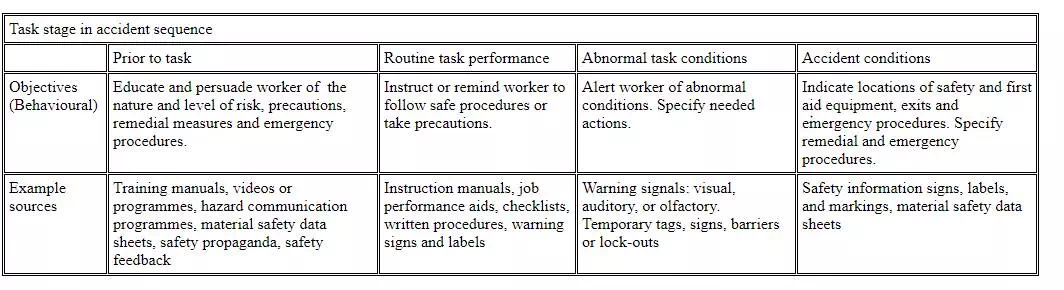

The behavioural objectives of particular sources of safety information correspond or “map” naturally to the four different stages of the accident sequence.

Objectives and example sources of safety information mapped to the accident sequence

1. First stage. At the first stage in the accident sequence, sources of information provided prior to the task, such as safety training materials, hazard communication programmes and various forms of safety programme materials (including safety posters and campaigns) are used to educate workers about risks and persuade them to behave safely. Methods of education and persuasion (behaviour modification) attempt not only to reduce errors by improving worker knowledge and skills but also to reduce intentional violations of safety rules by changing unsafe attitudes. Inexperienced workers are often the target audience at this stage, and therefore the safety information is much more detailed in content than at the other stages. It must be emphasized that a well-trained and motivated workforce is a prerequisite for safety information to be effective at the three following stages of the accident sequence.

2. Second stage. At the second stage in the accident sequence, sources such as written procedures, checklists, instructions, warning signs and product labels can provide critical safety information during routine task performance. This information usually consists of brief statements which either instruct less skilled workers or remind skilled workers to take necessary precautions. Following this approach can help prevent workers from omitting either precautions or other critical steps in a task. Statements providing such information are often embedded at the appropriate stage within step-by-step instructions describing how to perform a task. Warning signs at appropriate locations can play a similar role: for example, a warning sign located at the entrance to a workplace might state that safety hard hats must be worn inside.

3. Third stage. At the third stage in the accident sequence, highly conspicuous and easily perceived sources of safety information alert workers of abnormal or unusually hazardous conditions. Examples include warning signals, safety markings, tags, signs, barriers or lock-outs. Warning signals can be visual (flashing lights, movements, etc.), auditory (buzzers, horns, tones, etc.), olfactory (odours), tactile (vibrations) or kinaesthetic. Certain warning signals are inherent to products when they are in hazardous states (e.g., the odour released upon opening a container of acetone). Others are designed into machinery or work environments (e.g., the back-up signal on a fork-lift truck). Safety markings refer to methods of non-verbally identifying or highlighting potentially hazardous elements of the environment (e.g., by painting step edges yellow or emergency stops red). Safety tags, barriers, signs or lock-outs are placed at points of hazard and are often used to prevent workers from entering areas or activating equipment during maintenance, repair or other abnormal conditions.

4. Fourth stage. At the fourth stage in the accident sequence, the focus is on expediting worker performance of emergency procedures at the time an accident is occurring, or on the performance of remedial measures shortly after the accident. Safety information signs and markings conspicuously indicate facts critical to adequate performance of emergency procedures (e.g., the locations of exits, fire extinguishers, first aid stations, emergency showers, eyewash stations or emergency releases). Product safety labels and MSDSs may specify remedial and emergency procedures to be followed.

However, if safety information is to be effective at any stage in the accident sequence, it must first be noticed and understood, and if the information has been previously learned, it must also be remembered. Then the worker must both decide to comply with the provided message and be physically able to do so. Successfully attaining each of these steps for effectiveness can be difficult; however, guidelines describing how to design safety information are of some assistance.

Design Guidelines and Requirements

Standards-making organizations, regulatory agencies and the courts through their decisions have traditionally both instituted guidelines and imposed requirements regarding when and how safety information is to be provided. More recently, there has been a trend towards developing guidelines based on scientific research concerning the factors which influence the effectiveness of safety information.

Legal requirements

In most industrialized countries, government regulations require that certain forms of safety information be provided to workers. For example, in the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed several labelling requirements for toxic chemicals. The Department of Transportation (DOT) makes specific provisions regarding the labelling of hazardous materials in transport. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has promulgated a hazard communication standard that applies to workplaces where toxic or hazardous materials are in use, which requires training, container labelling, MSDSs and other forms of warnings.

In the United States, the failure to warn also can be grounds for litigation holding manufacturers, employers and others liable for injuries incurred by workers. In establishing liability, the Theory of Negligence takes into consideration whether the failure to provide adequate warning is judged to be unreasonable conduct based on (1) the foreseeability of the danger by the manufacturer, (2) the reasonableness of the assumption that a user would realize the danger and (3) the degree of care that the manufacturer took to inform the user of the danger. The Theory of Strict Liability requires only that the failure to warn caused the injury or loss.

Voluntary standards

A large set of existing standards provide voluntary recommendations regarding the use and design of safety information. These standards have been developed by multilateral groups and agencies, such as the United Nations, the European Economic Community (EEC’s EURONORM), the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC); and by national groups, such as the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), the British Standards Institute, the Canadian Standards Association, the German Institute for Normalization (DIN) and the Japanese Industrial Standards Committee.

Among consensus standards, those developed by ANSI in the United States are of special significance. Since the mid-1980s, five new ANSI standards focusing on safety signs and labels have been developed and one significant standard has been revised. The new standards are:

1. ANSI Z535.1, Safety Color Code,

2. ANSI Z535.2, Environmental and Facility Safety Signs,

3. ANSI Z535.3, Criteria for Safety Symbols,

4. ANSI Z535.4, Product Safety Signs and Labels, and

5. ANSI Z535.5, Accident Prevention Tags. The recently revised standard is ANSI Z129.1–1988, Hazardous Industrial Chemicals—Precautionary Labeling. Furthermore, ANSI has published the Guide for Developing Product Information.

Design specifications

Design specifications can be found in consensus and governmental safety standards specifying how to design the following:

1. Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDSs). The OSHA hazard communication standard specifies that employers must have a MSDS in the workplace for each hazardous chemical used. The standard requires that each sheet be written in English, list its date of preparation and provide the scientific and common names of the hazardous chemical mentioned. It also requires the MSDS to describe (1) physical and chemical characteristics of the hazardous chemical, (2) physical hazards, including potential for fire, explosion and reactivity, (3) health hazards, including signs and symptoms of exposure, and health conditions potentially aggravated by the chemical, (4) the primary route of entry, (5) the OSHA permissible exposure limit, the ACGIH threshold limit value or other recommended limits, (6) carcinogenic properties, (7) generally applicable precautions, (8) generally applicable control measures, (9) emergency and first aid procedures and (10) the name, address and telephone number of a party able to provide, if necessary, additional information on the hazardous chemical and emergency procedures.

2. Instructional labels and manuals. Few consensus standards currently specify how to design instructional labels and manuals. This situation is, however, quickly changing. The ANSI Guide for Developing User Product Information was published in 1990, and several other consensus organizations are working on draft documents. Without an overly scientific foundation, the ANSI Consumer Interest Council, which is responsible for the above guidelines, has provided a reasonable outline to manufacturers regarding what to consider in producing instruction/operator manuals. They have included sections entitled: “Organizational Elements”, “Illustrations”, “Instructions”, “Warnings”, “Standards”, “How to Use Language”, and “An Instructions Development Checklist”. While the guideline is brief, the document represents a useful initial effort in this area.

3. Safety symbols. Numerous standards throughout the world contain provisions regarding safety symbols. Among such standards, the ANSI Z535.3 standard, Criteria for Safety Symbols, is particularly relevant for industrial users. The standard presents a significant set of selected symbols shown in previous studies to be well understood by workers in the United States. Perhaps more importantly, the standard also specifies methods for designing and evaluating safety symbols. Important provisions include the requirement that (1) new symbols must be correctly identified during testing by at least 85% of 50 or more representative subjects, (2) symbols which don’t meet the above criteria should be used only when equivalent printed verbal messages are also provided and (3) employers and product manufacturers should train workers and users regarding the intended meaning of the symbols. The standard also makes new symbols developed under these guidelines eligible to be considered for inclusion in future revisions of the standard.

4. Warning signs, labels and tags. ANSI and other standards provide very specific recommendations regarding the design of warning signs, labels and tags. These include, among other factors, particular signal words and text, colour coding schemes, typography, symbols, arrangement and hazard identification. Among the most popular signal words recommended are: DANGER, to indicate the highest level of hazard; WARNING, to represent an intermediate hazard; and CAUTION, to indicate the lowest level of hazard. Colour coding methods are to be used to consistently associate colours with particular levels of hazard. For example, red is used in all of the standards in to represent DANGER, the highest level of hazard. Explicit recommendations regarding typography are given in nearly all the systems. The most general commonality between the systems is the recommended use of sans-serif typefaces. Varied recommendations are given regarding the use of symbols and pictographs. The FMC and the Westinghouse systems advocate the use of symbols to define the hazard and to convey the level of hazard (FMC 1985; Westinghouse 1981). Other standards recommend symbols only as a supplement to words. Another area of substantial variation, pertains to the recommended label arrangements. The proposed arrangements generally include elements discussed above and specify the image (graphic content or colour), the background (shape, colour); the enclosure (shape, colour) and the surround (shape, colour). Many of the systems also precisely describe the arrangement of the written text and provide guidance regarding methods of hazard identification.

Table 56.5 Summary of recommendations within selected warning systems

|

System |

Signal words |

Colour coding |

Typography |

Symbols |

Arrangement |

|

ANSI Z129.1 Hazardous Industrial Chemicals: Precautionary Labeling (1988) |

Danger |

Not specified |

Not specified |

Skull-and-crossbones as

supplement to words. |

Label arrangement not specified; examples given |

|

ANSI Z535.2 Environmental and Facility Safety Signs (1993) |

Danger |

Red |

Sans serif, upper case, acceptable typefaces, letter heights |

Symbols and pictographs per ANSI Z535.3 |

Defines signal word, word message, symbol panels in 1 to 3 panel designs. 4 shapes for special use. Can use ANSI Z535.4 for uniformity. |

|

ANSI Z535.4 Product Safety Signs and Labels (1993) |

Danger |

Red |

Sans serif, upper case, suggested typefaces, letter heights |

Symbols and pictographs per ANSI Z535.3; also SAE J284 safety alert symbol |

Defines signal word, message, pictorial panels in order of general to specific. Can use ANSI Z535.2 for uniformity. Use ANSI Z129.1 for chemical hazards. |

|

NEMA Guidelines: NEMA 260 (1982) |

Danger |

Red |

Not specified |

Electric shock symbol |

Defines signal word, hazard, consequences, instructions, symbol. Does not specify order. |

|

SAE J115 Safety Signs (1979) |

Danger |

Red |

Sans serif typeface, upper case |

Layout to accommodate symbols; specific symbols/ pictographs not prescribed |

Defines 3 areas: signal word panel, pictorial panel, message panel. Arrange in order of general to specific. |

|

ISO Standard: ISO R557 (1967); ISO 3864 (1984) |

None. 3 kinds of

labels: |

|

Message panel is added below if necessary |

Symbols and pictographs |

Pictograph or symbol is placed inside appropriate shape with message panel below if necessary |

|

OSHA 1910.145 Specification for Accident Prevention Signs and Tags (1985) |

Danger |

Red |

Readable at 5 feet or as required by task |

Biological hazard symbol. Major message can be supplied by pictograph (tags only). Slow-moving vehicle (SAE J943) |

Signal word and major message (tags only) |

|

OSHA 1910.1200 (Chemical) Hazard Communication (1985) |

Per applicable requirements of EPA, FDA, BATF, and CPSC; not otherwise specified. |

|

In English |

|

Only as Material Safety Data Sheet |

|

Westinghouse Handbook (1981); FMC Guidelines (1985) |

Danger |

Red |

Helvetica bold and regular weights, upper/lower case |

Symbols and pictographs |

Recommends 5 components: signal word, symbol/pictograph, hazard, result of ignoring warning, avoiding hazard |

Certain standards may also specify the content and wording of warning signs or labels in some detail. For example, ANSI Z129.1 specifies that chemical warning labels must include

(1)identification of the chemical product or its hazardous component(s),

(2)a signal word,

(3)a statement of hazard(s),

(4)precautionary measures,

(5)instructions in case of contact or exposure,

(6)antidotes,

(7)notes to physicians,

(8)instructions in case of fire and spill or leak and

(9)instructions for container handling and storage.

This standard also specifies a general format for chemical labels that incorporate these items. The standard also provides extensive and specific recommended wordings for particular messages.

Cognitive guidelines

Design specifications, such as those discussed above, can be useful to developers of safety information. However, many products and situations are not directly addressed by standards or regulations. Certain design specifications may not be scientifically proven, and, in extreme cases, conforming with standards and regulations may actually reduce the effectiveness of safety information. To ensure effectiveness, developers of safety information consequently may need to go beyond safety standards. Recognizing this issue, the International Ergonomics Association (IEA) and International Foundation for Industrial Ergonomics and Safety Research (IFIESR) recently supported an effort to develop guidelines for warning signs and labels (Lehto 1992) which reflect published and unpublished studies on effectiveness and have implications regarding the design of nearly all forms of safety information. Six of these guidelines, presented in slightly modified form, are as follows.

1. Match sources of safety information to the level of performance at which critical errors occur for a given population. In specifying what and how safety information is to be provided, this guideline emphasizes the need to focus attention on (1) critical errors that can cause significant damage and (2) the level of worker performance at the time the error is made. This objective often can be attained if sources of safety information are matched to behavioural objectives consistently with the mapping and discussed earlier.

2. Integrate safety information into the task and hazard-related context. Safety information should be provided in a way that makes it likely to be noticed at the time it is most relevant, which almost always is the moment when action needs to be taken. Recent research has confirmed that this principle is true for both the placement of safety messages within instructions and the placement of safety information sources (such as warning signs) in the physical environment. One study showed that people were much more likely to notice and comply with safety precautions when they were included as a step within instructions, rather than separated from instructional text as a separate warning section. It is interesting to observe that many safety standards conversely recommend or require that precautionary and warning information be placed in a separate section.

3. Be selective. Providing excessive amounts of safety information increases the time and effort required to find what is relevant to the emergent need. Sources of safety information should consequently focus on providing relevant information which does not exceed what is needed for the immediate purpose. Training programmes should provide the most detailed information. Instruction manuals, MSDSs and other reference sources should be more detailed than warning signs, labels or signals.

4. Keep the cost of compliance within a reasonable level. A substantial number of studies have indicated that people become less likely to follow safety precautions when doing so is perceived to involve a significant “cost of compliance”. Safety information should therefore be provided in a way that minimizes the difficulty of complying with its message. Occasionally this goal can be attained by providing the information at a time and location when complying is convenient.

5. Make symbols and text as concrete as possible. Research has shown that people are better able to understand concrete, rather than abstract, words and symbols used within safety information. Skill and experience, however, play a major role in determining the value of concreteness. It is not unusual for highly skilled workers to both prefer and better understand abstract terminology.

6. Simplify the syntax and grammar of text and combinations of symbols. Writing text that poor readers, or even adequate readers, can comprehend is not an easy task. Numerous guidelines have been developed in attempts to alleviate such problems. Some basic principles are (1) use words and symbols understood by the target audience, (2) use consistent terminology, (3) use short, simple sentences constructed in the standard subject-verb-object form, (4) avoid negations and complex conditional sentences, (5) use the active rather than passive voice, (6) avoid using complex pictographs to describe actions and (7) avoid combining multiple meanings in a single figure.

Satisfying these guidelines requires consideration of a substantial number of detailed issues as addressed in the next section.

Developing Safety Information

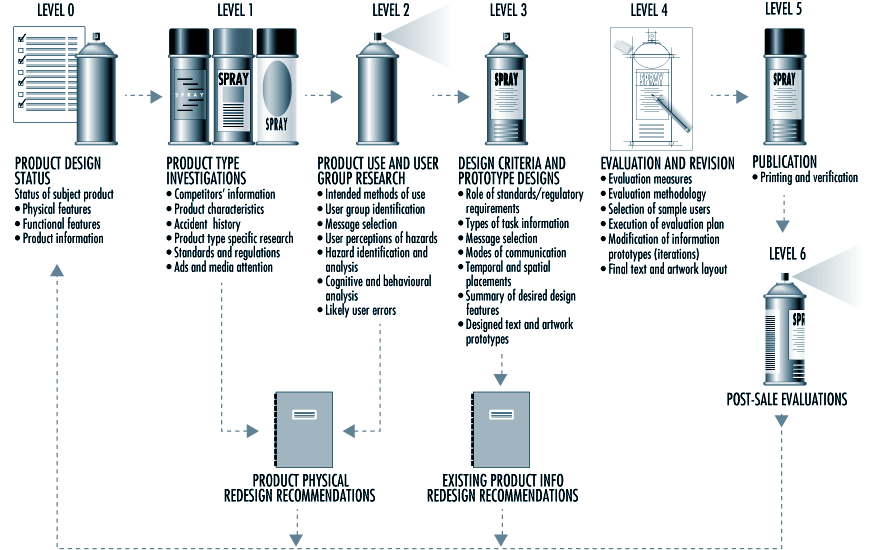

The development of safety information meant to accompany products, such as safety warnings, labels and instructions, often requires extensive investigations and development activities involving considerable resources and time. Ideally, such activities (1) coordinate the development of product information with design of the product itself, (2) analyse product features which affect user expectations and behaviours, (3) identify the hazards associated with use and likely misuse of the product, (4) research user perceptions and expectations regarding product function and hazard characteristics and (5) evaluate product information using methods and criteria consistent with the goals of each component of product information. Activities accomplishing these objectives can be grouped into several levels. While in-house product designers are able to accomplish many of the tasks designated, some of these tasks involve the application of methodologies most familiar to professionals with backgrounds in human factors engineering, safety engineering, document design and the communication sciences. Tasks falling within these levels are summarized

A model for designing and evaluating product information

Level 0: Product design status

Level 0 is both the starting point for initiating a product information project, and the point at which feedback regarding design alternatives will be received and new iterations at the basic model level will be forwarded. At the initiation of a product information project, the researcher begins with a particular design. The design can be in the concept or prototype stage or as currently being sold and used. A major reason for designating a Level 0 is the recognition that the development of product information must be managed. Such projects require formal budgets, resources, planning, and accountability. The largest benefits to be gained from a systematic product information design are achieved when the product is in the pre-production concept or prototype state. However, applying the methodology to existing products and product information is quite appropriate and extremely valuable.

Level 1: Product type investigations

At least seven tasks should be performed at this stage:

1. document characteristics of the existing product (e.g., parts, operation, assembly and packaging),

2. investigate the design features and accompanying information for similar or competitive products,

3. collect data on accidents for both this product and similar or competitive products,

4. identify human factors and safety research addressing this type of product,

5. identify applicable standards and regulations,

6. analyse government and commercial media attention to this type of product (including recall information) and

7. research the litigation history for this and similar products.

Level 2: Product use and user group research

At least seven tasks should be performed at this stage:

1. determine appropriate methods for use of product (including assembly, installation, use and maintenance),

2. identify existing and potential product user groups,

3. research consumer use, misuse, and knowledge of product or similar products,

4. research user perceptions of product hazards,

5. identify hazards associated with intended use(s) and foreseeable misuse(s) of product,

6. analyse cognitive and behavioural demands during product use and

7. identify likely user errors, their consequences and potential remedies.

After completing the analyses in Levels 1 and 2, product design changes should be considered before proceeding further. In the traditional safety engineering sense, this could be called “engineering the hazard out of the product”. Some modifications may be for the health of the consumer, and some for the benefit of the company as it attempts to produce a marketing success.

Level 3: Information design criteria and prototypes

In Level 3 at least nine tasks are performed:

1. determine from the standards and requirements applying to the particular product which if any of those requirements impose design or performance criteria on this part of the information design,

2. determine those types of tasks for which information is to be provided to users (e.g., operation, assembly, maintenance and disposal),

3. for each type of task information, determine messages to be conveyed to user,

4. determine the mode of communication appropriate for each message (e.g., text, symbols, signals or product features),

5. determine temporal and spatial location of individual messages,

6. develop desired features of information based on messages, modes and placements developed in previous steps,

7. develop prototypes of individual components of product information system (e.g., manuals, labels, warnings, tags, advertisements, packaging and signs),

8. verify that there is consistency across the various types of information (e.g., manuals, advertisements, tags and packaging) and

9. verify that products with other brand names or similar existing products from the same company have consistent information.

After having proceeded through Levels 1, 2 and 3, the researcher will have developed the format and content of information expected to be appropriate. At this point, the researcher may want to provide initial recommendations regarding the redesign of any existing product information before moving on to Level 4.

Level 4: Evaluation and revision

In Level 4 at least six tasks are performed:

1. define evaluation parameters for each prototype component of the product information system,

2. develop an evaluation plan for each prototype component of the product information system,

3. select representative users, installers and so on, to participate in evaluation,

4. execute the evaluation plan,

5. modify product information prototypes and/or the design of the product based on the results obtained during evaluation (several iterations are likely to be necessary) and

6. specify the final text and artwork layout.

Level 5: Publication

Level 5, the actual publication of the information, is reviewed, approved and accomplished as specified. The purpose at this level is to confirm that specifications for designs, including designated logical groupings of material, location and quality of illustrations, and special communication features have been precisely followed, and have not been unintentionally modified by the printer. While the publication activity is usually not under the control of the person developing the information designs, we have found it necessary to verify that such designs are precisely followed, the reason being that printers have been known to take great liberties in manipulating design layout.

Level 6: Post-sale evaluations

The last level of the model deals with the post-sale evaluations, a final check to ensure that the information is indeed fulfilling the goals it was designed to achieve. The information designer as well as the manufacturer gains an opportunity for valuable and educational feedback from this process. Examples of post-sale evaluations include

1. feedback from customer satisfaction programmes,

2. potential summarization of data from warranty fulfilments and warranty response cards,

3. gathering of information from accident investigations involving the same or similar products,

4. monitoring of consensus standards and regulatory activities and

5. monitoring of safety recalls and media attention to similar products.

Workers who are the victims of work-related accidents suffer from material consequences, which include expenses and loss of earnings, and from intangible consequences, including pain and suffering, both of which may be of short or long duration. These consequences include:

· doctor’s fees, cost of ambulance or other transport, hospital charges or fees for home nursing, payments made to persons who gave assistance, cost of artificial limbs and so on

· the immediate loss of earnings during absence from work (unless insured or compensated)

· loss of future earnings if the injury is permanently disabling, long term or precludes the victim’s normal advancement in his or her career or occupation

· permanent afflictions resulting from the accident, such as mutilation, lameness, loss of vision, ugly scars or disfigurement, mental changes and so on, which may reduce life expectancy and give rise to physical or psychological suffering, or to further expenses arising from the victim’s need to find a new occupation or interests

· subsequent economic difficulties with the family budget if other members of the family have to either go to work to replace lost income or give up their employment in order to look after the victim. There may also be additional loss of income if the victim was engaged in private work outside normal working hours and is no longer able to perform it.

· anxiety for the rest of the family and detriment to their future, especially in the case of children.

Workers who become victims of accidents frequently receive compensation or allowances both in cash and in kind. Although these do not affect the intangible consequences of the accident (except in exceptional circumstances), they constitute a more or less important part of the material consequences, inasmuch as they affect the income which will take the place of the salary. There is no doubt that part of the overall costs of an accident must, except in very favourable circumstances, be borne directly by the victims.

Considering the national economy as a whole, it must be admitted that the interdependence of all its members is such that the consequences of an accident affecting one individual will have an adverse effect on the general standard of living, and may include the following:

· an increase in the price of manufactured products, since the direct and indirect expenses and losses resulting from an accident may result in an increase in the cost of making the product

· a decrease in the gross national product as a result of the adverse effects of accidents on people, equipment, facilities and materials; these effects will vary according to the availability in each country of workers, capital and material resources

· additional expenses incurred to cover the cost of compensating accident victims and pay increased insurance premiums, and the amount necessary to provide safety measures required to prevent similar occurrences.

One of the functions of society is that it must protect the health and income of its members. It meets these obligations through the creation of social security institutions, health programmes (some governments provide free or low-cost medical care to their constituents), injury compensation insurance and safety systems (including legislation, inspection, assistance, research and so on), the administrative costs of which are a charge on society.

The level of compensation benefits and the amount of resources devoted to accident prevention by governments are limited for two reasons: because they depend (1) on the value placed on human life and suffering, which varies from one country to another and from one era to another; and (2) on the funds available and the priorities allocated for other services provided for the protection of the public.

As a result of all this, a considerable amount of capital is no longer available for productive investment. Nevertheless, the money devoted to preventive action does provide considerable economic benefits, to the extent that there is a reduction in the total number of accidents and their cost. Much of the effort devoted to the prevention of accidents, such as the incorporation of higher safety standards into machinery and equipment and the general education of the population before working age, are equally useful both inside and outside the workplace. This is of increasing importance because the number and cost of accidents occurring at home, on the road and in other non-work-related activities of modern life continues to grow. The total cost of accidents may be said to be the sum of the cost of prevention and the cost of the resultant changes. It would not seem unreasonable to recognize that the cost to society of the changes which could result from the implementation of a preventive measure may exceed the actual cost of the measure many times over. The necessary financial resources are drawn from the economically active section of the population, such as workers, employers and other taxpayers through systems which work either on the basis of contributions to the institutions that provide the benefits, or through taxes collected by the state and other public authorities, or by both systems. At the level of the undertaking the cost of accidents includes expenses and losses, which are made up of the following:

· expenses incurred while setting up the system of work and the related equipment and machinery with a view to ensuring safety in the production process. Estimation of these expenses is difficult because it is not possible to draw a line between the safety of the process itself and that of the workers. Major sums are involved which are entirely expended before production commences and are included in general or special costs to be amortized over a period of years.

· expenses incurred during production, which in turn include: (1) fixed charges related to accident prevention, notably for medical, safety and educational services and for arrangements for the workers’ participation in the safety programme; (2) fixed charges for accident insurance, plus variable charges in schemes where premiums are based on the number of accidents; (3) varying charges for activities related to accident prevention (these depend largely on accident frequency and severity, and include the cost of training and information activities, safety campaigns, safety programmes and research, and workers’ participation in these activities); (4) costs arising from personal injuries (These include the cost of medical care, transport, grants to accident victims and their families, administrative and legal consequences of accidents, salaries paid to injured persons during their absence from work and to other workers during interruptions to work after an accident and during subsequent inquiries and investigations, and so on.); (5) costs arising from material damage and loss which need not be accompanied by personal injury. In fact, the most typical and expensive material damage in certain branches of industry arises in circumstances other than those which result in personal injury; attention should be concentrated upon the few points in common between the techniques of material damage control and those required for the prevention of personal injury.

· losses arising out of a fall in production or from the costs of introducing special counter-measures, both of which may be very expensive.

In addition to affecting the place where the accident occurred, successive losses may occur at other points in the plant or in associated plants; apart from economic losses which result from work stoppages due to accidents or injuries, account must be taken of the losses resulting when the workers stop work or come out on strike during industrial disputes concerning serious, collective or repeated accidents.

The total value of these costs and losses are by no means the same for every undertaking. The most obvious differences depend on the particular hazards associated with each branch of industry or type of occupation and on the extent to which appropriate safety precautions are applied. Rather than trying to place a value on the initial costs incurred while incorporating accident prevention measures into the system at the earliest stages, many authors have tried to work out the consequential costs. Among these may be cited: Heinrich, who proposed that costs be divided into “direct costs” (particularly insurance) and “indirect costs” (expenses incurred by the manufacturer); Simonds, who proposed dividing the costs into insured costs and non-insured costs; Wallach, who proposed a division under the different headings used for analysing production costs, viz. labour, machinery, maintenance and time expenses; and Compes, who defined the costs as either general costs or individual costs. In all of these examples (with the exception of Wallach), two groups of costs are described which, although differently defined, have many points in common.

In view of the difficulty of estimating overall costs, attempts have been made to arrive at a suitable value for this figure by expressing the indirect cost (uninsured or individual costs) as a multiple of the direct cost (insured or general costs). Heinrich was the first to attempt to obtain a value for this figure and proposed that the indirect costs amounted to four times the direct costs—that is, that the total cost amounts to five times the direct cost. This estimation is valid for the group of undertakings studied by Heinrich, but is not valid for other groups and is even less valid when applied to individual factories. In a number of industries in various industrialized countries this value has been found to be of the order of 1 to 7 (4 ± 75%) but individual studies have shown that this figure can be considerably higher (up to 20 times) and may even vary over a period of time for the same undertaking.

There is no doubt that money spent incorporating accident prevention measures into the system during the initial stages of a manufacturing project will be offset by the reduction of losses and expenses that would otherwise have been incurred. This saving is not, however, subject to any particular law or fixed proportion, and will vary from case to case. It may be found that a small expenditure results in very substantial savings, whereas in another case a much greater expenditure results in very little apparent gain. In making calculations of this kind, allowance should always be made for the time factor, which works in two ways: current expenses may be reduced by amortizing the initial cost over several years, and the probability of an accident occurring, however rare it may be, will increase with the passage of time.

In any given industry, where permitted by societal factors, there may be no financial incentive to reduce accidents in view of the fact that their cost is added to the production cost and is thus passed on to the consumer. This is a different matter, however, when considered from the point of view of an individual undertaking. There may be a great incentive for an undertaking to take steps to avoid the serious economic effects of accidents involving key personnel or essential equipment. This is particularly so in the case of small plants which do not have a reserve of qualified staff, or those engaged in certain specialized activities, as well as in large, complex facilities, such as in the process industry, where the costs of replacement could surpass the capacity to raise capital. There may also be cases where a larger undertaking can be more competitive and thus increase its profits by taking steps to reduce accidents. Furthermore, no undertaking can afford to overlook the financial advantages that stem from maintaining good relations with workers and their trade unions.

As a final point, when passing from the abstract concept of an undertaking to the concrete reality of those who occupy senior positions in the business (i.e., the employer or the senior management), there is a personal incentive which is not only financial and which stems from the desire or the need to further their own career and to avoid the penalties, legal and otherwise, which may befall them in the case of certain types of accident. The cost of occupational accidents, therefore, has repercussions on both the national economy and that of each individual member of the population: there is thus an overall and an individual incentive for everybody to play a part in reducing this cost.