Quality Assurance Era

1950s marks the beginning of a new quality era, where the concept of quality evolved from being controlled to being guaranteed. As mentioned, the view of quality at the time was narrowed down to the factory level, and there is no communication or coordination between departments, making the quality control process only happen on the work floor. The process of quality control is remaining in on trying to find defects, which mean it is a reactive process. So by proactively looking at the problem concerning quality, the Quality Assurance era brings a new breed of tooling and approaches into play, with the four key elements: Cost of Quality, Total Quality Control, Reliability Engineering and Zero-defect.

Cost of Quality: Production-focused

Joseph M. Juran first come to Japan in 1954. Little did he know, his contribution to the growth of Japan’s concept of quality is the turning point. His 1951’s Quality Control Handbook, he moved the responsibilities to ensure quality to all departments with the emphasis on the top management being the driving force. This is the first time, the importance of relationship between multiple divisions to maintain good quality is mentioned in a publication. Enterprises are aware of the need to implement a quality control system to reduce the impact on profits. And by asking top manager a question that never been mentioned before: “How much quality is enough?”, he gives them a whole new perspective on the issue. This is the cornerstone of the concept of quality cost.

At that time, the fact almost all companies are only looking at the quality spectrum as a way to satisfying customers demand by provide good products or services meaning that there are so many hindering issues concerning the cost of quality which were not underlined, and those problems usually are being dealt only when visible. So if management would get a hang on the lack of quality beforehand and continuing to improve their quality process, it could translate into competitive advantage, survival in a market or even being a market leader. Juran understands this problem, and by trying to divide the cost of quality into two groups and define them, could give the management team a better analogy on their situations.

According to Juran, Quality Cost can be divided into two type: unavoidable costs and avoidable costs. Unavoidable costs are the type of cost that cannot be impacted. Usually those costs are coming from tasks and processes such as inspection, sampling, sorting. Meanwhile, avoidable costs are the cost that we can get around if the quality of the product and service is good enough. This cost consists of resources that required from the process of scrapping, reworking and the work required to do those tasks. Juran also identified the costs of loss sales can also be included as a part of avoidable cost. He also noted that if these avoidable costs are minimized, it could lead to a sustainable increase in profits, thus calling avoidable costs “gold in the mine” of quality Juran’s proposal is considered a contradiction to the belief of where quality lies, and open a new portal on how to solve the problem related to expenditures to lower cost and increase quality. This approach is deemed antithetical and redesigned later, since at that moment, there are no ways to get around the unavoidable costs. We will go through this further on.

Total Quality Control

Total Quality is the term that was coiled by The New York Times. It definition is to achieve and maintain the highest quality throughout all level of operation within a company by working efficiently and producing high-quality products and services.

Juran’s ideology later is expanded by Armand Feigenbaum, suggested that the standard of quality can be achieved if more emphasis is put into managerial duty and on collaboration between multiple departments, or as Feigenbaum called, “inter-functional teams” (1961). He argued that if a product is controlled starting from the designing process to the point where customer received it, the quality of the product would achieve the perfect status, thus “Quality is everybody’s job”. He proposed to form cross-functional teams from multiple departments to control the product design and manufacture process with the intention to satisfy customers before and after. The problem of Feigenbaum’s proposal is, as pointed out by Garvin (1987), he does not consider the strategic aspect of Quality and only focused on the preproduction aspects of product design’s manufacturability.

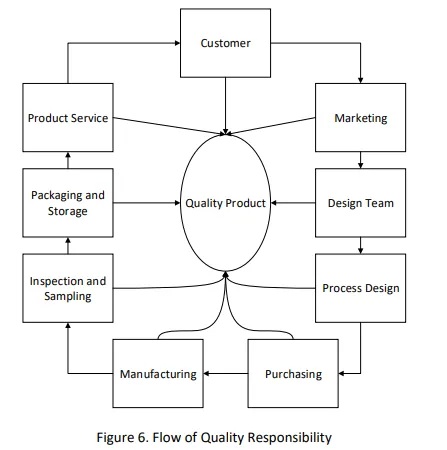

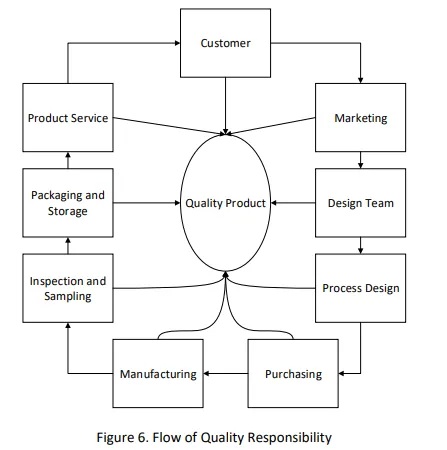

Feigenbaum also identified that when a product is made, it had to move through 3 stages: design control, incoming material control and shop floor control. This mean the whole supply chain system are involved in the process, so every single department are responsible for the outcome of their products. For design control, it is the marketing which collect the requirements from customers, then pass it to design team to make a prototype and set up specifications. Process design will determine what parts and components required to be bought and planning the manufacturing process. Shop floor control include inspection and sampling, packaging and storage.

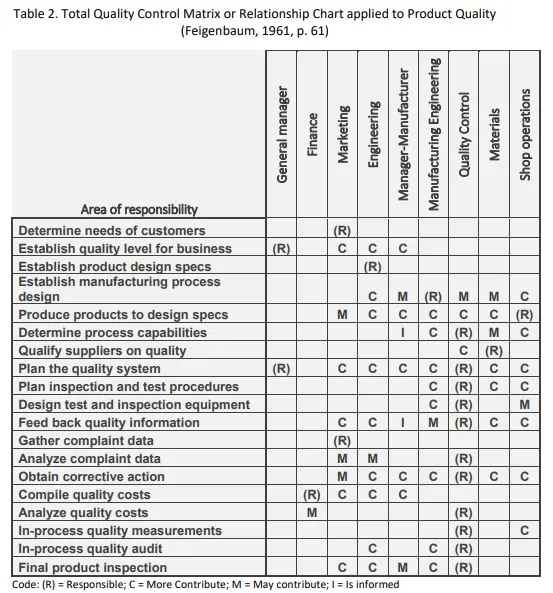

Still, Feigenbaum still heavily favors to put more responsibilities to the Quality Control department as we can see in his Matrix and Relationship Chart below.

Feigenbaum has started to realize the important of finding a quality suppliers to control the quality of the firm, but it is still limited to the view of the Procurement process and the Quality control department. A few years later, during 1960s, a branch of Total Quality Control started to develop in Japan by latching onto Feigenbaum’s concept. The approach was similar to American’s Total Quality Control, and some parts are even more developed than the American one. This approach is often referred to Company-Wide Quality Control. The two concept are still being used as criteria for their own national quality award, the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award for American, and the Deming Prize for Japanese.

Reliability Engineering

Although, Juran and Feigenhaum’s work focused more on the infrastructure of the company and the collaboration and cross-functional works, they thought applying statistical control into production is important. So, by adapting the military maintenance and logistics method in performance checking during the Korean Civil Wars, the US Engineers had adopted the method of Reliability Engineering. It is the study of the dependability of a product or service during its lifetime. By testing the product, engineers could identify the probability of failure, using statistics model to theory craft and predict the performance of the product under different interval of time and conditions. Several techniques are used at the time, some of which is still widely use in maintenance management these days, such as: - Failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA): how systematically a product could fail. - Individual components analysis: whether to remove or fix the components. - Derating: require items to be used under their specifications level. - Redundancy: parallel replacement to important components

Zero Defect

Zero defect is a management method of rallying and motivating workforce to achieve defects-free production and manufacturing. Before this, Quality Control is the study of how to reduce the number of defects, but there are no attempts whatsoever on trying to achieve perfect results. So, in 1961, at Martin Company, a missile company, tryout an ambitious plan of not relying on inspecting but rather on raising their worker’s morale and awareness, to produce perfect missiles, which carried out successfully. The CEO of Martin Company, James F. Halpin, later in his book Zero Defects: A New Dimension in Quality Assurance, he explained that if perfection were never to be expected in the first place, and mistakes are being treated as inevitable, then defects will happen. So, if the mindset can be changed, it is possible to achieve zero defects.

Halpin’s words are heavily based on philosophy and motivation, concentrated on the importance of the workforce. The CEO thinks that the old method of acceptance quality level, which is the direct paradoxical theory to zero defects, are not constraining the measurements good enough, which bring up a lot of debates and arguments and challenged the old way on not putting enough remarks on Quality. Zero Defects later is emphasized by Philip B. Crosby where he asserted that the only performance indication is Zero Defects. In his book “Quality is Free” (1979), he dismissed the thinking that Zero Defects is a motivation based program. Instead, he thought that when Zero Defects are reached, the Cost of Quality will be the Quality of the product itself, thus urged that everybody should have the mindset of “doing the job right the first time”, since people still think that they cannot avoid the inevitable error.

Quality Assurance era has set up a bridge of connection between company divisions on how to achieve the standard goal. People start to recognize how costly it is if Quality is ignored. But the approach to achieve Total Quality is still very reactive and only revolved around Defects. The next era moves away from that approach and focus more on gaining competitive edges through Quality.