Government and Society

Constitutional

framework

Under the 1999 constitution, executive

power is vested in a president who serves as both the head of state and the

chief executive, is directly elected to a four-year term, and nominates the

vice president and members of the cabinet. The constitution provides for a

bicameral National

Assembly, which

consists of the House of Representatives and the Senate. Each state elects 10

members to the House of Representatives for four-year terms; members of the

Senate—three from each state and one from the Federal Capital Territory—also

are elected to four-year terms.

Local government

There

are two tiers of government—state and local—below the federal level. The

functions of the government at the local level were usurped by the state

government until 1988, when the federal government decided to fund local

government organizations directly and allowed them for the first time to

function effectively.

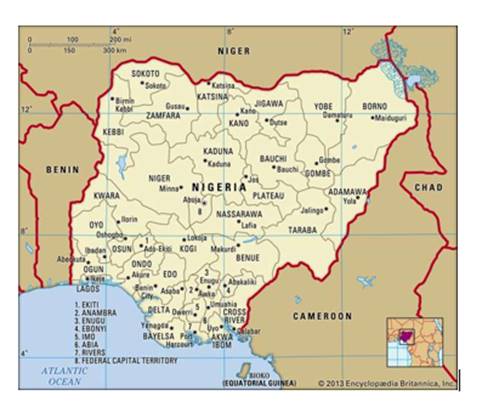

Nigeria

is divided into 36 states and the Federal

Capital Territory, where the country’s capital, Abuja, is

located; the constitution also includes a provision that more states can be

created as needed. At independence the country was divided into three regions:

Northern, Eastern, and Western. The Mid-West region was created out of the

Western region in 1963. In 1967 Col. Yakubu

Gowon, then the military leader, turned the regions into 12 states: 6 in the

north, 3 in the east, and 3 in the west. Gen. Murtala

Mohammed created an additional 7 states in 1976. Gen. Ibrahim Babangida created 11 more states—2 in 1987 and 9 in

1991—for a total of 30. In 1996 Gen. Sani Abacha added 6 more states.

Nigeria administrative boundaries in 1996Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Justice

The

Nigerian legal and judicial system contains

three codes of law: customary law, Nigerian statute law (following English

law), and Sharīʿah (Islamic law).

Customary laws, administered by native, or customary, courts, are usually

presided over by traditional rulers, who generally hear cases about family

problems such as divorce. Kadis (judges) apply Sharīʿah based on the Maliki Islamic code. Since

1999, several states have instituted Sharīʿah

law. Although the states claim that the law applies only to Muslims, the

minority non-Muslim population argues that it is affected by the law as well.

Christian women, for example, must ride on female-only buses, and some states

have banned females from participating in sports.

Nigerian statute law includes much of the British colonial legislation,

most of which has been revised. State legislatures may pass laws on matters

that are not part of the Exclusive Legislative List, which includes

such areas as defense, foreign policy, and

mining—all of which are the province of the federal government. Federal law

prevails whenever federal legislation conflicts with state legislation. In addition

to Nigerian statutes, English law is used in the magistrates’ and all higher

courts. Each state has a High Court, which is presided over by a chief judge.

The Supreme Court, headed by the

chief justice of Nigeria, is the

highest court.

Political process

The

constitution grants all citizens at least 18 years

of age the right to vote. The Action Group (AG) and the Northern

People’s Congress (NPC) were the major Nigerian parties when the country

became independent in 1960. However, their regional rather than national

focus—the AG represented the west, the NPC the north, and the National Council

for Nigeria and the Cameroons the east—ultimately contributed to the outbreak

of civil war by the mid-1960s and more than 20 years of military rule.

Political parties were allowed briefly in 1993 and again starting from 1998,

but only parties with national rather than regional representation were legal,

such as the newly created People’s Democratic Party (PDP), the

Alliance for Democracy, and the All Nigeria People’s Party. Since then,

many other parties have been created, most notably the All Progressives

Congress (APC), the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA), and the Labour

Party.

Women have participated in the government since the colonial period,

especially in the south. Their political strength is rooted in the precolonial traditions among particular ethnic groups, such

as the Igbo, which gave women the power to correct excessive male

behaviour (known as “sitting on a man”). Igbo women, showing their strength,

rioted in 1929 when they believed colonial officials were going to levy taxes

on women. Yoruba market women exercised significant economic power,

controlling the markets in such Yoruba cities as Lagos and Ibadan.

Some ethnic groups, such as the Edo who constituted the

kingdom of Benin, also gave important political power to women; the mother

of the oba (king) played an

important part in the precolonial state. Women such

as Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (the

mother of the musician Fela and human rights activist

and physician Beko) actively participated in the

colonial struggle, and several women have held ministerial positions in the

government. Although Nigerian women may wield influence and political power,

particularly at the familial and local level, this has not always been

reflected at the federal level: in the early 21st century, women made up about

5 percent of the House of Representatives and the

Senate. (For more information on the historical role of women in Nigerian

politics and culture, see Sidebar: Nigerian Women.)

Security

The Nigeria Police Force, established by

the federal constitution, is headed by the inspector general of police, who is

appointed by the president. The general inefficiency of the force is

attributable in part to the low level of education and the low morale of police

recruits, who are poorly housed and very poorly paid, and to the lack of modern

equipment. Corruption is widespread.

The federal military includes army, navy, and air

force contingents. Nigerian troops have participated in missions sponsored

by the Economic

Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) and by

the United Nations (UN).

Nigerian soldiers marching in Abuja, Nigeria, in

October 2010, during 50th anniversary celebrations of Nigerian independence.

Sunday Alamba/AP

Health and welfare

The concentration of people in the

cities has created enormous sanitary problems, particularly improper sewage

disposal, water shortages, and poor drainage. Large heaps of domestic refuse

spill across narrow streets, causing traffic delays, while the dumping of

garbage along streambeds constitutes a major health hazard and has

contributed to the floods that have often plagued Ibadan, Lagos, and other

cities during the rainy season. Lower respiratory infections, diarrheal

diseases, malaria, and HIV/AIDS are among the leading causes of

death. The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control was established in 2011 to

support public health.

Health

conditions are particularly poor in the shantytown suburbs of Greater Lagos and

other large cities, where domestic water supplies are obtained from wells that

are often polluted by seepage from pit latrines.

Rural communities also suffer from inadequate or impure water

supplies. Some villagers have to walk as far as 6 miles (10 km) to the nearest

water point—usually a stream. Because people wash clothes, bathe, and fish

(sometimes using fish poison) in the same streams, the water drawn by people in

villages farther downstream is often polluted. During the rainy season, wayside

pits containing rainwater, often dug close to residential areas, are the main

source of domestic water supplies. Cattle are often watered in the shallower

pools, and this contributes to the high incidence of intestinal diseases

and guinea worm in many rural areas.

Medical

and health services are the responsibility of all levels of government. There

are hospitals in the large cities and towns. Most of the state capitals have

specialized hospitals, and many are home to a university teaching hospital.

There are numerous private hospitals, clinics, and maternity centres. Medical

services are inadequate in many parts of the country, however, because of

shortages of medical personnel, modern equipment, and supplies.

Housing

Overcrowding in the cities has

caused slums to spread and shantytown suburbs to emerge in most of the larger

urban centres. Most houses are built by individuals, and, because banks do not

normally lend money for home construction, most of these individuals must rely

on their savings. A federal housing program provides funds for the construction

of low-cost housing for low- and middle-income workers in the state capitals,

local government headquarters, and other large towns.

House

types vary by geographic location. In the coastal areas the walls and roofs are

made from the raffia palm, which abounds in the region. Rectangular mud houses

with mat roofs are found in the forest belt, although the houses of the more

prosperous have corrugated iron roofs. In the savanna

areas of the central region and in parts of the north, houses are round mud

buildings roofed with sloping grass thatch, but flat mud roofs appear in the

drier areas of the extreme north. Some mud houses are also covered with a layer

of cement. Larger houses are designed around an open courtyard and

traditionally contained barrels or cisterns in which rainwater could be

collected.

·

·

Nigeria: housing in Dareta

Health-care workers near a thatch-roofed mud dwelling in the village of Dareta, Zamfara state, northern

Nigeria.

Nigeria:

architecture

Clay houses decorated with low-relief ornament and vibrant designs,

exhibiting contemporary vernacular architecture in Zaria, Nigeria.

During the colonial period, British officials lived in

segregated housing known as Government Reserve Areas (GRA). After independence

GRA housing became very desirable among the African population.

Education

Great Britain did little to promote education during

the colonial period. Until 1950 most schools were operated by Christian

missionary bodies, which introduced Western-style education into Nigeria

beginning in the mid-19th century. The British colonial government funded a few

schools, although its policy was to give grants to mission schools rather than

to expand its own system. In the northern, predominantly Muslim area,

Western-style education was prohibited because the religious leaders did not

want Christian missionaries interfering with Islam, and Islamic education

was provided in traditional Islamic schools.

Today primary

education, free and compulsory, begins at age six and lasts for six years.

Secondary education consists of two three-year cycles, the first cycle of which

is free and compulsory. Although federal and state governments have the major

responsibility for education, other organizations, such as local governments

and religious groups, may establish and administer primary and secondary

schools. Most secondary schools, trade centres, technical institutes,

teacher-training colleges, and colleges of education and of technology are

controlled by the state governments.

Nigeria

has more than 400 universities and colleges widely dispersed throughout the

country in an attempt to make higher education easily accessible.

Many of the universities are federally controlled, and the language of

instruction is English at all the universities and colleges. At the time of

Nigeria’s independence in 1960, there were only two established postsecondary

institutions, both of which were located in the southwestern

part of the country: University College at Ibadan (founded in 1948, now the University of Ibadan) and Yaba Higher College (founded in 1934, now Yaba College of Technology). Four more government-operated

universities were established in the 1960s: University of Nigeria, Nsukka (1960), in the east; University of Ife (founded

in 1961, now Obafemi Awolowo

University) in the west; University of Northern Nigeria (founded in 1962, now Ahmadu

Bello University) in the north; and University of Lagos (1962) in the south. In the 1970s and

’80s the government attempted to found a university in every state, but, with

the ever-increasing number of states, this practice was abandoned. Numerous

federal and state universities have since been established, especially during

the 21st century. Attempts by individuals and private organizations, including

various Christian churches, to establish universities did not receive the

approval of the federal Ministry of Education until the 1990s. Since then,

dozens of private postsecondary institutions have been established.

Cultural Life

Cultural

milieu

Nigeria’s rich and varied cultural

heritage derives from the mixture of its ethnic groups with Arabic and western

European influences. The country combines traditional culture with

international urban sophistication. Secret societies, such as Ekpo and Ekpe among

the Igbo, were formerly used as instruments of government, while other

institutions were associated with matrimony. According to

the Fulani custom of sharo (test

of young manhood), rival suitors underwent the ordeal of caning as a means of

eliminating those who were less persistent. In Ibibio territory,

girls approaching marriageable age were confined for several years in

bride-fattening rooms before they were given to their husbands. A girl was

well-fed during this confinement, with the intent of making her plump and

therefore more attractive to her future husband; she would also receive

instruction from older women on how to be a good wife. These and other customs

were discouraged by colonial administrators and missionaries. Some of the more

adaptable cultural institutions have been revived since independence; these

include Ekpo and Ekong

societies for young boys in parts of the southeast and the Ogboni

society found in the Yoruba and Edo areas of southern

Nigeria. (For information on the historical role of women in Nigerian society, see Sidebar:

Nigerian Women.)

Nigeria’s vibrant popular culture reflects

great changes in inherited traditions and adaptations of imported ones.

Establishments serving alcoholic beverages are found everywhere except where

Islamic laws prohibit them. Hotels and nightclubs are part of the landscape of

the larger cities. Movie theatres, showing mostly Indian and American films,

are popular among the urban middle- and low-income groups. Radio, television,

and other forms of home entertainment (e.g., recorded music and movies) have

also grown in popularity, though their use is dependent on the availability of

electricity.

Whether

in urban or rural areas, the family is the central institution. Families gather

to celebrate births and weddings. Funerals are also times when the family

gathers. Because so many Nigerians live outside the country, funerals for

non-Muslims are often delayed for a month or more to allow all the family

members to make plans to return home.

A bride and groom posing with their

wedding guests in Nigeria.

Food is an important

part of Nigerian life. Seafood, beef, poultry, and goat are the primary sources

of protein. With so many different cultures and regions, food can

vary greatly. In the southern areas a variety of soups containing a base of

tomatoes, onions, red pepper, and palm oil are prepared with vegetables such as

okra and meat or fish. Soups can be thickened by adding ground egusi (melon)

seeds. Gari (ground

cassava), iyan (yam paste),

or plantains accompany the soup. Rice is eaten throughout the country, and in

the north grains such as millet and wheat are a large part of the

diet. Beans and root vegetables are ubiquitous. Many dishes are flavoured

with onions, palm oil, and chilies.