Federalism: Division of Powers

The Division of Powers

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

v Explain the concept of federalism

v Discuss the constitutional logic of federalism

v Identify the powers and responsibilities of federal, state, and local governments

Modern democracies divide governmental power in two general ways; some, like the United States, use a combination of both structures. The first and more common mechanism shares power among three branches of government—the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. The second, federalism, apportions power between two levels of government: national and subnational. In the United States, the term federal government refers to the government at the national level, while the term states means governments at the subnational level.

Federalism Defined and Contrasted

Federalism is an institutional arrangement that creates two relatively autonomous levels of government, each possessing the capacity to act directly on behalf of the people with the authority granted to it by the national constitution.

Although today’s federal systems vary in design, five structural characteristics are common to the United States and other federal systems around the world, including Germany and Mexico.

First, all federal systems establish two levels of government, with both levels being elected by the people and each level assigned different functions. The national government is responsible for handling matters that affect the country as a whole, for example, defending the nation against foreign threats and promoting national economic prosperity. Subnational, or state governments, are responsible for matters that lie within their regions, which include ensuring the well-being of their people by administering education, health care, public safety, and other public services. By definition, a system like this requires that different levels of government cooperate, because the institutions at each level form an interacting network. In the U.S. federal system, all national matters are handled by the federal government, which is led by the president and members of Congress, all of whom are elected by voters across the country. All matters at the subnational level are the responsibility of the fifty states, each headed by an elected governor and legislature. Thus, there is a separation of functions between the federal and state governments, and voters choose the leader at each level.

The second characteristic common to all federal systems is a written national constitution that cannot be changed without the substantial consent of subnational governments. In the American federal system, the twenty-seven amendments added to the Constitution since its adoption were the result of an arduous process that required approval by two-thirds of both houses of Congress and three-fourths of the states. The main advantage of this supermajority requirement is that no changes to the Constitution can occur unless there is broad support within Congress and among states. The potential drawback is that numerous national amendment initiatives—such as the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which aims to guarantee equal rights regardless of sex—have failed because they cannot garner sufficient consent among members of Congress or, in the case of the ERA, the states.

Third, the constitutions of countries with federal systems formally allocate legislative, judicial, and executive authority to the two levels of government in such a way as to ensure each level some degree of autonomy from the other. Under the U.S. Constitution, the president assumes executive power, Congress exercises legislative powers, and the federal courts (e.g., U.S. district courts, appellate courts, and the Supreme Court) assume judicial powers. In each of the fifty states, a governor assumes executive authority, a state legislature makes laws, and state-level courts (e.g., trial courts, intermediate appellate courts, and supreme courts) possess judicial authority.

While each level of government is somewhat independent of the others, a great deal of interaction occurs among them. In fact, the ability of the federal and state governments to achieve their objectives often depends on the cooperation of the other level of government. For example, the federal government’s efforts to ensure homeland security are bolstered by the involvement of law enforcement agents working at local and state levels. On the other hand, the ability of states to provide their residents with public education and health care is enhanced by the federal government’s financial assistance.

Another common characteristic of federalism around the world is that national courts commonly resolve disputes between levels and departments of government. In the United States, conflicts between states and the federal government are adjudicated by federal courts, with the U.S. Supreme Court being the final arbiter. The resolution of such disputes can preserve the autonomy of one level of government, as illustrated recently when the Supreme Court ruled that states cannot interfere with the federal government’s actions relating to immigration.

In other instances, a Supreme Court ruling can erode that autonomy, as demonstrated in the 1940s when, in United States v. Wrightwood Dairy Co., the Court enabled the federal government to regulate commercial activities that occurred within states, a function previously handled exclusively by the states.

Finally, subnational governments are always represented in the upper house of the national legislature, enabling regional interests to influence national lawmaking.[

In the American federal system, the U.S. Senate functions as a territorial body by representing the fifty states: Each state elects two senators to ensure equal representation regardless of state population differences. Thus, federal laws are shaped in part by state interests, which senators convey to the federal policymaking process.

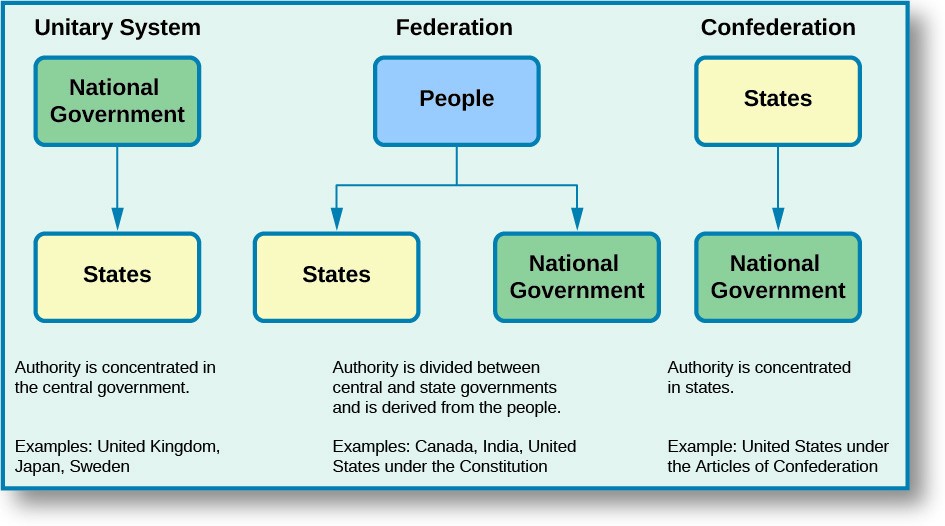

Division of power can also occur via a unitary structure or confederation. In contrast to federalism, a unitary system makes subnational governments dependent on the national government, where significant authority is concentrated. Before the late 1990s, the United Kingdom’s unitary system was centralized to the extent that the national government held the most important levers of power. Since then, power has been gradually decentralized through a process of devolution, leading to the creation of regional governments in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland as well as the delegation of specific responsibilities to them. Other democratic countries with unitary systems, such as France, Japan, and Sweden, have followed a similar path of decentralization.

Figure 1. There are three general systems of government—unitary systems, federations, and confederations—each of which allocates power differently.

In a confederation, authority is decentralized, and the central government’s ability to act depends on the consent of the subnational governments. Under the Articles of Confederation (the first constitution of the United States), states were sovereign and powerful while the national government was subordinate and weak. Because states were reluctant to give up any of their power, the national government lacked authority in the face of challenges such as servicing the war debt, ending commercial disputes among states, negotiating trade agreements with other countries, and addressing popular uprisings that were sweeping the country. As the brief American experience with confederation clearly shows, the main drawback with this system of government is that it maximizes regional self-rule at the expense of effective national governance.

Federalism and the Constitution

The Constitution contains several provisions that direct the functioning of U.S. federalism. Some delineate the scope of national and state power, while others restrict it. The remaining provisions shape relationships among the states and between the states and the federal government.

The enumerated powers of the national legislature are found in Article I, Section 8. These powers define the jurisdictional boundaries within which the federal government has authority. In seeking not to replay the problems that plagued the young country under the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution’s framers granted Congress specific powers that ensured its authority over national and foreign affairs. To provide for the general welfare of the populace, it can tax, borrow money, regulate interstate and foreign commerce, and protect property rights, for example. To provide for the common defense of the people, the federal government can raise and support armies and declare war. Furthermore, national integration and unity are fostered with the government’s powers over the coining of money, naturalization, postal services, and other responsibilities.

The last clause of Article I, Section 8, commonly referred to as the elastic clause or the necessary and proper cause, enables Congress “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying” out its constitutional responsibilities. While the enumerated powers define the policy areas in which the national government has authority, the elastic clause allows it to create the legal means to fulfill those responsibilities. However, the open-ended construction of this clause has enabled the national government to expand its authority beyond what is specified in the Constitution, a development also motivated by the expansive interpretation of the commerce clause, which empowers the federal government to regulate interstate economic transactions.

The powers of the state governments were never listed in the original Constitution. The consensus among the framers was that states would retain any powers not prohibited by the Constitution or delegated to the national government.[6]

However, when it came time to ratify the Constitution, a number of states requested that an amendment be added explicitly identifying the reserved powers of the states. What these Anti-Federalists sought was further assurance that the national government’s capacity to act directly on behalf of the people would be restricted, which the first ten amendments (Bill of Rights) provided. The Tenth Amendment affirms the states’ reserved powers: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Indeed, state constitutions had bills of rights, which the first Congress used as the source for the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

Some of the states’ reserved powers are no longer exclusively within state domain, however. For example, since the 1940s, the federal government has also engaged in administering health, safety, income security, education, and welfare to state residents. The boundary between intrastate and interstate commerce has become indefinable as a result of broad interpretation of the commerce clause. Shared and overlapping powers have become an integral part of contemporary U.S. federalism. These concurrent powers range from taxing, borrowing, and making and enforcing laws to establishing court systems.[7]

Article I, Sections 9 and 10, along with several constitutional amendments, lay out the restrictions on federal and state authority. The most important restriction Section 9 places on the national government prevents measures that cause the deprivation of personal liberty. Specifically, the government cannot suspend the writ of habeas corpus, which enables someone in custody to petition a judge to determine whether that person’s detention is legal; pass a bill of attainder, a legislative action declaring someone guilty without a trial; or enact an ex post facto law, which criminalizes an act retroactively. The Bill of Rights affirms and expands these constitutional restrictions, ensuring that the government cannot encroach on personal freedoms.