What is polarizing legislatures? Probably not what you think.

Four hundred years ago this July, 22 elected officials gathered at the edge of the James River to write some rules affecting the lives of residents of the Virginia Colony. The weather was hot and unpleasant, several members were ill, and one died during the brief session. Nonetheless, the group ratified a charter and passed a number of laws, including the levying of a tax, before adjourning. This was, for all intents and purposes, the first session of the first American state legislature.

I was honored to recently join a group of scholars in putting together a symposium at PS: Political Science & Politics on what weíve learned about state legislatures in the past four centuries. (These articles are ungated for the next month.) The articles include:

∑ Richard Clucas on the enduring relevance of state legislatures

∑ Peverill Squire on their early colonial history

∑ Keith Hamm on the state of research on these chambers

∑ Beth Reingold on the legislative representation of women and racial and ethnic minorities

∑ Gary Moncrief on the institutional development and capacity of legislatures

∑ Shanna Rose on the influence of state legislatures in national politics

I commend each of these to your attention. But I wanted to talk a bit about my own article, which is an assessment of party polarization in state legislatures.

We hear pundits and politicians and reformers make all sort of claims about the causes of partisanship in Congress, from the length of legislative sessions to redistricting to campaign spending to primary election rules and more. And itís very difficult to prove or disprove any of these ideas if youíre only focusing on one legislature. When we turn our attention to the statehouses, though, we get a lot more variation in the institutional rules and political environments affecting legislators, and we can say with greater certainty just what is and what isnít causing polarization.

To be sure, polarization is increasing in our state legislatures, as it is in Congress, but not uniformly. In a handful of states, weíve actually seen depolarization in the past few decades, as Boris Shor and Nolan McCartyís evidence shows us. So why have some states, like California and Colorado, polarized rapidly? Why have Connecticutís and Kentuckyís state Senates depolarized?

GOOD MEDIA COVERAGE MAKES LEGISLATORS WANT TO VOTE WITH THEIR CONSTITUENTS LEST THEY APPEAR TO BE A BAD FIT FOR THEIR DISTRICT. BUT IF NO ONEíS WATCHING THEM, ITíS HARD FOR VOTERS TO CARE ABOUT THIS.

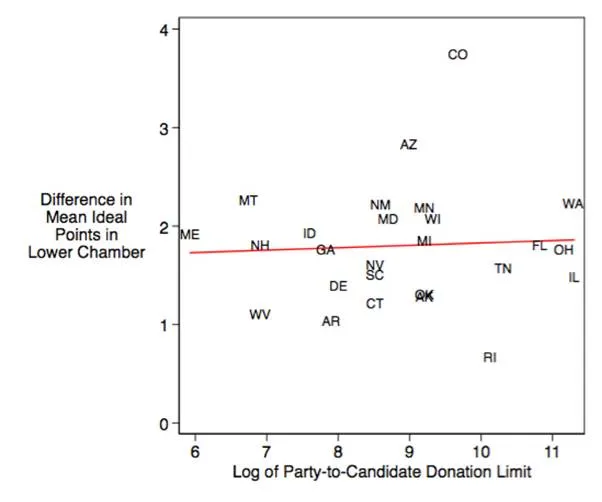

I explore a few explanations, and I find little if any evidence to support various folk theories about polarization. For example, does spending by parties cause greater polarization? This is certainly a common theory among political observers, and itís helped support a large number of state restrictions on party spending in elections on the belief that doing so would free up officeholders from strict partisan behavior. In fact, the simple scatter plot below shows that states with higher donation limits on parties are no more or less polarized than states with lower donation limits. (In their recent book, Ray La Raja and Brian Schaffner actually find the reverse to be true: Limits on party spending cause more polarization.)

Figure: State Party Donation Limits Predicting Polarization in State Legislatures

I go through a few of these folk theories and find that legislative polarization is unrelated to:

∑ Legislative professionalism

∑ Chamber size

∑ Redistricting

∑ The openness of primaries.

So what is causing legislative polarization? Notably, it isnít the sort of thing thatís easy to fix. A review of some research suggests that modern polarization in statehouses is being driven by:

Economic inequality. Weíve known for years that inequality and polarization track each other, but some recent research suggests that the former is causing the latter.

The distribution of public opinion. If legislators have a pretty good sense of public opinion in their districts, they can follow that pretty well to ensure their own reelections. But if they have more complex districts and itís not easy to figure out what most voters want, legislators may just follow what their party wants.

The decline of state political journalism. Coverage of state legislatures has been declining for decades, and the gutting of various local newspapers recently has made this worse. Good coverage makes legislators want to vote with their constituents lest they appear to be a bad fit for their district. But if no oneís watching them, itís hard for voters to care about this.

On top of these other factors, the parties have been sorting into rigid ideological camps nationally and within states for the past half century, and those camps are reinforced by race, gender, class, geography, religion, and more.

These factors donít lend themselves to easy fixes by a long shot. But if weíve decided that polarization really is a problem, it would be good to focus on what is actually associated with it rather than whatís easy to change. And if weíre going to try to fix national problems, it would be good to look at evidence from the states.