Social Movements

Social Movements

Social movements are broad alliances of people connected through a shared interest in either stopping or instigating social change.

Social movements are broad alliances of people who are connected through their shared interest in social change. Social movements can advocate for a particular social change, but they can also organize to oppose a social change that is being advocated by another entity. These movements do not have to be formally organized to be considered social movements. Different alliances can work separately for common causes and still be considered a social movement.

Sociologists draw distinctions between social movements and social movement organizations (SMOs). A social movement organization is a formally organized component of a social movement. Therefore, it may represent only one part of a particular social movement. For instance, PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) advocates for vegan lifestyles along with its other aims. However, PETA is not the only group that advocates for vegan diets and lifestyles; there are numerous other groups actively engaged toward this end. Thus, promoting veganism would be considered the social movement, while PETA would be considered a particular SMO (social movement organization) working within the broader social movement.

Modern social movements became possible through the wide dissemination of literature and the increased mobility of labor, both of which have been caused by the industrialization of societies. Anthony Giddens, a renowned sociologist, has identified four areas in which social movements operate in modern societies:

· democratic movements that work for political rights

· labor movements that work for control of the workplace

· ecological movements that are concerned with the environment

· peace movements that work toward peace

It is interesting to note that social movements can spawn counter movements. For instance, the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s resulted in a number of counter movements that attempted to block the goals of the women’s movement. In large part, these oppositional groups formed because the women’s movement advocated for reform in conservative religions.

Types of Social Movements

Social movements occur when large groups of individuals or organizations work for or against change in social and/or political matters.

Social movements are a specific type of group action in which large informal groups of individuals or organizations work for or against change in specific political or social issues.

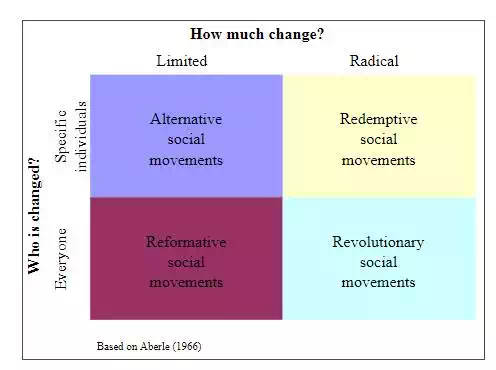

Cultural Anthropologist David F. Aberle described four types of social movements based upon two fundamental questions: (1) who is the movement attempting to change? (2) how much change is being advocated? Social movements can be aimed at change on an individual level, e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous, which is a support group for recovering alcoholics or change on a broader group or even societal level, e.g. anti-globalization). Social movements can also advocate for minor changes such as tougher restrictions on drunk driving (see MADD) or radical changes like prohibition. The diagram below illustrates how a social movement may either be alternative, redemptive, reformative or revolutionary based on who the movement strives to change and how much change the movement desires to bring about.

Aberle’s Four Types of Social Movements: Based on who a movement is trying to change and how much change a movement is advocating, Aberle identified four types of social movements: redemptive, reformative, revolutionary and alternative.

Other categories have been used to distinguish between types of social movements.

· Scope: A movement can be either reform or radical. A reform movement advocates changing some norms or laws while a radical movement is dedicated to changing value systems in some fundamental way. A reform movement might be a trade union seeking to increase workers’ rights while the American Civil Rights movement was a radical movement.

· Type of Change: A movement might seek change that is either innovative or conservative. An innovative movement wants to introduce or change norms and values while a conservative movement seeks to preserve existing norms and values.

· Targets: Group-focused movements focus on influencing groups or society in general; for example, attempting to change the political system from a monarchy to a democracy. An individual-focused movement seeks to affect individuals.

· Methods of Work: Peaceful movements utilize techniques such as nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience. Violent movements resort to violence when seeking social change.

· Range: Global movements, such as Communism in the early 20th century, have transnational objectives. Local movements are focused on local or regional objectives such as preserving an historic building or protecting a natural habitat.

Propaganda and the Mass Media

Mass media can be employed to manipulate populations to further the power elite’s agenda.

The propaganda model is a conceptual model in political economy advanced by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky to explain how propaganda and systemic biases function in mass media. The model seeks to explain how populations are manipulated and how consent for economic, social and political policies is “manufactured” in the public mind due to this propaganda. The theory posits that the way in which news is structured (e.g. through advertising, concentration of media ownership, government sourcing) creates an inherent conflict of interest which acts as propaganda for undemocratic forces.

An example that Herman and Chomsky identified was “anti-communism” during the Cold War. Such anti- ideologies exploit public fear and hatred of groups that pose a potential threat, either real, exaggerated or imagined. Communism once posed the primary threat, and communism and socialism were portrayed by their detractors as endangering freedoms of speech, movement, the press and so forth. They argue that such a portrayal was often used as a means to silence voices critical of elite interests.

The Power Elite is a 1956 book by sociologist C. Wright Mills, in which Mills calls attention to the interwoven interests of the leaders of the military, corporate, and political elements of society and suggests that the ordinary citizen is a relatively powerless subject of manipulation by those entities.

According to Mills, the eponymous “power elite” are those that occupy the dominant positions, in the dominant institutions (military, economic and political) of a dominant country, and their decisions (or lack of decisions) have enormous consequences, not only for the U.S. population but, “the underlying populations of the world.”

These two models—the propaganda and the “power elite” conceptualization—evidence how mass media can be used to reinforce the powerful’s positions of power and interests. For example:

· During the Gulf War (1990), the media’s failure to report on Saddam Hussein’s peace offers guided the public to look more favorably on the U.S. government’s actions.

· During the Iraq invasion (2003), the media’s failure to report on the legality of the war, despite overwhelming public opinion in favor of only invading Iraq with UN authorization, minimized public awareness and outcry over that illegality. According to the liberal watchdog group Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting, there was a disproportionate focus on pro-war sources while total anti-war sources only made up 10% of the media (with only 3% of US sources being anti-war).

· With regard to global warming, the media (in the interest of those who make a tremendous amount of money from fossil fuels) gives near equal balance to people who deny climate change, despite only “about one percent” of climate scientists taking this view. This allows the “debate” to continue, when in reality there is firm scientific consensus, in turn allowing those corporations to continue profiting off human behavior that in reality harms the environment.

The Stages of Social Movements

Social movements typically follow a process by which they emerge, coalesce, and bureaucratize, leading to their success or failure.

Charles Tilly defines social movements as a series of contentious performances, displays and campaigns by which ordinary people make collective claims on others. For Tilly, social movements are a major vehicle for ordinary people’s participation in public politics. Sidney Tarrow defines a social movement as collective challenges [to elites , authorities , other groups or cultural codes] by people with common purposes and solidarity in sustained interactions with elites, opponents and authorities. He specifically distinguishes social movements from political parties and advocacy groups. The term “social movements” was introduced in 1848 by the German Sociologist Lorenz von Stein in his book Socialist and Communist Movements since the Third French Revolution (1848).

Social movements are not eternal. They have a life cycle: they are created, they grow, they achieve successes or failures and, eventually, they dissolve and cease to exist.

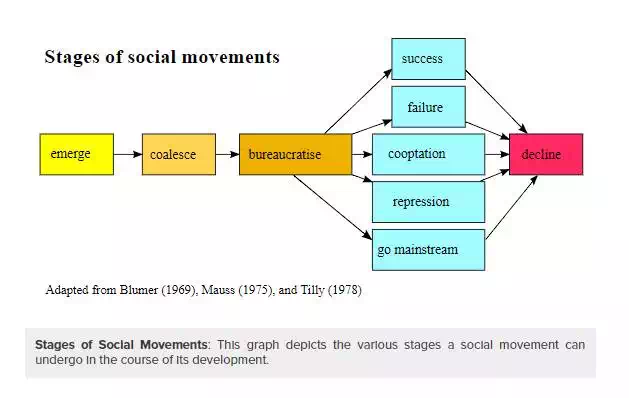

Blumer, Mauss, and Tilly have described the different stages that social movements often pass through (see ). Firstly, movements emerge for a variety of reasons (and there are a number of different sociological theories that address these reasons). They then coalesce and develop a sense of coherence in terms of membership, goals and ideals. In the next stage, movements generally become bureaucratized by establishing their own set of rules and procedures. At this point, social movements can then take any number of paths, ranging from success to failure, the cooptation of leaders, repression by larger groups (e.g., government), or even the establishment of a movement within the mainstream.

Frame analysis, and specifically frame transformation, helps explain why social movements occur in a certain way. The concept dates back to Erving Goffman, and it discuss how new values, new meanings and understandings are required in order to understand and support social movements or changes. In other words, people must transform the way they understand a particular social movement to make it fit with conventional lifestyles and rituals.

Whether or not these paths will result in movement decline varies from movement to movement. In fact, one of the difficulties in studying social movements is that movement success is often ill-defined because the goals of a movement can change. For instance, MoveOn.org, a website founded in the late 1990s, was originally developed to encourage national politicians to move past the Clinton impeachment proceedings. Since that time, the group has developed into a major player in national politics in the U.S. and transformed into a Political Action Committee (PAC). In this instance, the movement may or may not have attained its original goal—encouraging the censure of Clinton and moving on to more pressing issues—but the goals of the movement have changed. This makes the actual stages the movement has passed through difficult to discern.

Relative Deprivation Approach

Social scientists have cited ‘relative deprivation’ as a potential cause of social movements and deviance.

Relative deprivation is the experience of being deprived of something to which one feels to be entitled. It refers to the discontent that people feel when they compare their positions to those around them and realize that they have less of that which they believe themselves to be entitled. Social scientists, particularly political scientists and sociologists, have cited ‘relative deprivation’ (especially temporal relative deprivation) as a potential cause of social movements and deviance. In extreme situations, it can lead to political violence such as rioting, terrorism, civil wars and other instances of social deviance such as crime. Some scholars explain the rise of social movements by citing the grievances of people who feel that they have been deprived of values to which they are entitled. Similarly, individuals engage in deviant behaviors when their means do not match their goals.

Feelings of deprivation are relative, as they come from a comparison to social norms that are not absolute and usually differ from time and place. This differentiates relative deprivation from objective deprivation (also known as absolute deprivation or absolute poverty ), a condition that applies to all underprivileged people. This leads to an important conclusion: while the objective deprivation (poverty) in the world may change over time, relative deprivation will not, as long as social inequality persists and some humans are better off than others. Relative deprivation may be temporal; that is, it can be experienced by people that experience expansion of rights or wealth, followed by stagnation or reversal of those gains. Such phenomena are also known as unfulfilled rising expectations.

Some sociologists—for instance, Karl Polanyi—have argued that relative differences in economic wealth are more important than absolute deprivation, and that this is a more significant determinate of human quality of life. This debate has important consequences for social policy, particularly on whether poverty can be eliminated simply by raising total wealth or whether egalitarian measures are also needed. A specific form of relative deprivation is relative poverty. A measure of relative poverty defines poverty as being below some relative poverty line, such as households who earn less than 20% of the median income. Notice that if everyone’s real income in an economy increases, but the income distribution stays the same, the number of people living in relative poverty will not change.Critics of this theory have pointed out that this theory fails to explain why some people who feel discontent fail to take action and join social movements. Counter-arguments include that some people are prone to conflict-avoidance, are short-term-oriented, or that imminent life difficulties may arise since there is no guarantee that life-improvement will result from social action.

Resource Mobilization Approach

The resource-mobilization approach is a theory that seeks to explain the emergence of social movements.

Resource-Mobilization Theory emphasizes the importance of resources in social movement development and success. Resources are understood here to include: knowledge, money, media, labor, solidarity, legitimacy, and internal and external support from a power elite. The theory argues that social movements develop when individuals with grievances are able to mobilize sufficient resources to take action. The emphasis on resources explains why some discontented/deprived individuals are able to organize while others are not. Resource mobilization theory also divides social movements according to their position among other social movements. This helps sociologists understand them in relation to other social movements; for example, how much influence does one theory or movement have on another?

Some of the assumptions of the theory include:

· there will always be grounds for protest in modern, politically pluralistic societies because there is constant discontent (i.e., grievances or deprivation); this de-emphasizes the importance of these factors as it makes them ubiquitous

· actors are rational and they are able to weigh the costs and benefits from movement participation

· members are recruited through networks; commitment is maintained by building a collective identity and continuing to nurture interpersonal relationships

· movement organization is contingent upon the aggregation of resources

· social movement organizations require resources and continuity of leadership

· social movement entrepreneurs and protest organizations are the catalysts which transform collective discontent into social movements; social movement organizations form the backbone of social movements

· the form of the resources shapes the activities of the movement (e.g., access to a TV station will result in the extensive use TV media)

· movements develop in contingent opportunity structures, which are external factors that may either limit or bolster the movement, that influence their efforts to mobilize. Examples of opportunity structures may include elements, such as the influence of the state, a movement’s access to political institutions, etc. As each movement’s response to the opportunity structures depends on the movement’s organization and resources, there is no clear pattern of movement development nor are specific movement techniques or methods universal.

Critics of this theory argue that there is too much of an emphasis on resources, especially financial resources. Some movements are effective without an influx of money and are more dependent upon the movement of members for time and labor (e.g., the civil rights movement in the US).

Gender and Social Movements

The feminist movement refers to a series of campaigns on issues pertaining to women, such as reproductive rights and women’s suffrage.

The feminist movement refers to a series of campaigns for reforms on issues such as reproductive rights, domestic violence, maternity leave, equal pay, women’s suffrage, sexual harassment and sexual violence. The movement’s priorities vary among nations and communities and range from opposition to female genital mutilation in one country or to the glass ceiling (the barrier that prevents minorities and women from advancing in corporate hierarchies ) in another. First-wave feminism refers to a period of feminist activity during the 19th and early twentieth century in the United Kingdom, Canada, the Netherlands and the United States. It focused on de jure (officially mandated) inequalities, primarily on gaining women’s suffrage (the right to vote).

Second-wave feminism refers to a period of feminist activity beginning in the early 1960s and through the late 1980s. Second Wave Feminism has existed continuously since then, and continues to coexist with what some people call Third Wave Feminism. Second wave feminism saw cultural and political inequalities as inextricably linked. The movement encouraged women to understand aspects of their personal lives as deeply politicized, and reflective of a sexist structure of power. If first-wavers focused on absolute rights such as suffrage, second-wavers were largely concerned with other issues of equality, such as the end to discrimination.

Finally, the third-wave of feminism began in the early 1990s. The movement arose as responses to what young women thought of as perceived failures of the second-wave. It was also a response to the backlash against initiatives and movements created by the second-wave. Third-wave feminism seeks to challenge or avoid what it deems the second wave’s “essentialist ” definitions of femininity, which (according to them) over-emphasized the experiences of upper middle class white women. A post-structuralist interpretation of gender and sexuality is central to much of the third wave’s ideology. Third wave feminists often focus on “micropolitics,” and challenged the second wave’s paradigm as to what is, or is not, good for females.

Global Feminism

Immediately after WWII, a new global dimension was added to the feminist cause through the formation of the United Nations (UN). In 1946 the UN established a Commission on the Status of Women. In 1948 the UN issued its Universal Declaration of Human Rights which protects “the equal rights of men and women”, and addressed both equality and equity issues. Since 1975 the UN has held a series of world conferences on women’s issues, starting with the World Conference of the International Women’s Year in Mexico City, heralding the United Nations Decade for Women (1975–1985). These have brought women together from all over the world and provided considerable opportunities for advancing women’s rights, but also illustrated the deep divisions in attempting to apply principles universally, in successive conferences in Copenhagen (1980) and Nairobi (1985). However by 1985 some convergence was appearing. These divisions among feminists included: First World vs. Third World; the relationship between gender oppression and oppression based on class, race and nationality; defining core common elements of feminism vs. specific political elements; defining feminism, homosexuality, female circumcision, birth and population control; the gulf between researchers and the grass roots; and the extent to which political issues were women’s issues. Emerging from Nairobi was a realization that feminism is not monolithic but “constitutes the political expression of the concerns and interests of women from different regions, classes, nationalities, and ethnic backgrounds. There is and must be a diversity of feminisms, responsive to the different needs and concerns of women, and defined by them for themselves. This diversity builds on a common opposition to gender oppression and hierarchy which, however, is only the first step in articulating and acting upon a political agenda. ” The fourth conference was held in Beijing in 1995. At this conference a the Beijing Platform for Action was signed. This included a commitment to achieve ” gender equality and the empowerment of women”. The most important strategy to achieve this was considered to be “gender mainstreaming ” which incorporates both equity and equality, that is that both women and men should “experience equal conditions for realizing their full human rights, and have the opportunity to contribute and benefit from national, political, economic, social and cultural development. ”

International Women’s Day Rally: International Women’s Day rally in Dhaka, Bangladesh, organized by the National Women Workers Trade Union Centre on 8 March 2005.

New Social Movements

New social movements focus on issues related to human rights, rather than on materialistic concerns, such as economic development.

New Social Movements

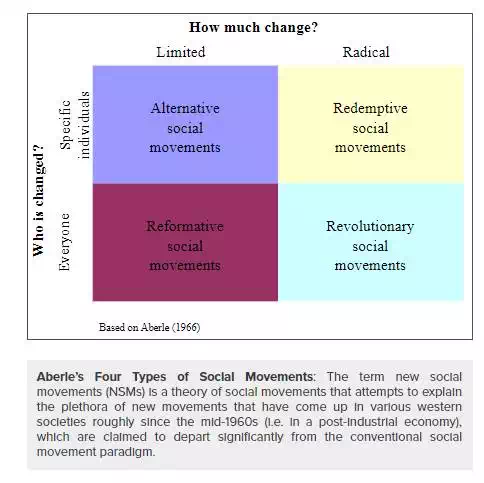

The term new social movements (NSMs) is a theory of social movements that attempts to explain the plethora of new movements that have come up in various western societies roughly since the mid-1960s (i.e. in a post-industrial economy), which are claimed to depart significantly from the conventional social movement paradigm.

There are two central claims of the NSM theory. Firstly, the rise of the post-industrial economy is responsible for a new wave of social movement. Secondly, these movements are significantly different from previous social movements of the industrial economy. The primary difference is in their goals, as the new movements focus not on issues of materialistic qualities such as economic well-being, but on issues related to human rights (such as gay rights or pacifism).

Characteristics

The most noticeable feature of new social movements is that they are primarily social and cultural and only secondarily, if at all, political. Departing from the worker’s movement, which was central to the political aim of gaining access to citizenship and representation for the working class, new social movements concentrate on bringing about social mobilization through cultural innovations, the development of new lifestyles, and the transformation of identities. It is clearly elaborated by Habermas that new social movements are the “new politics ” which is about quality of life, individual self-realization, and human rights; whereas the “old politics” focused on economic, political, and military security. The concept of new politics can be exemplified in gay liberation, the focus of which transcends the political issue of gay rights to address the need for a social and cultural acceptance of homosexuality. Hence, new social movements are understood as “new,” because they are first and foremost social, unlike older movements which mostly have an economic basis.

New social movements also emphasize the role of post-material values in contemporary and post-industrial society, as opposed to conflicts over material resources. According to Melucci, one of the leading new social movement theorists, these movements arise not from relations of production and distribution of resources, but within the sphere of reproduction and the life world. Consequently, the concern has shifted from the production of economic resources as a means of survival or for reproduction to cultural production of social relations, symbols, and identities. In other words, the contemporary social movements reject the materialistic orientation of consumerism in capitalist societies by questioning the modern idea that links the pursuit of happiness and success closely to growth, progress, and increased productivity and by instead promoting alternative values and understandings in relation to the social world. As an example, the environmental movement that has appeared since the late 1960s throughout the world, with its strong points in the United States and Northern Europe, has significantly brought about a “dramatic reversal” in the ways we consider the relationship between economy, society, and nature.

Further, new social movements are located in civil society or the cultural sphere as a major arena for collective action rather than instrumental action in the state, which Claus Offe characterizes as “bypass[ing] the state. ” Moreover, since new social movements are not normally concerned with directly challenging the state, they are regarded as anti-authoritarian and as resisting incorporation at the institutional level. They tend to focus on a single issue, or a limited range of issues connected to a single broad theme, such as peace or the environment. New social movements concentrate on the grassroots level with the aim to represent the interests of marginal or excluded groups. Therefore, new collective actions are locally based, centered on small social groups and loosely held together by personal or informational networks such as radios, newspapers, and posters. This “local- and issue-centered” characteristic implies that new movements do not necessarily require a strong ideology or agreement to meet their objectives.

Additionally, if old social movements, namely the worker’s movement, presupposed a working class base and ideology, the new social movements are presumed to draw from a different social class base, i.e., “the new class. ” This is a complex contemporary class structure that Claus Offe identifies as “threefold” in its composition: the new middle class, elements of the old middle class, and peripheral groups outside the labor market. As stated by Offe, the new middle class has evolved in association with the old one in the new social movements because of its high levels of education and its access to information and resources. The groups of people that are marginal in the labor market, such as students, housewives, and the unemployed participate in the collective actions as a consequence of their higher levels of free time, their position of being at the receiving end of bureaucratic control, and their inability to be fully engaged in society specifically in terms of employment and consumption.