Bioplastics and biodegradable plastics

From cars to food wrap and from planes to pens, you can make anything and everything from plastics—unquestionably the world's most versatile materials. But there's a snag. Plastics are synthetic (artificially created) chemicals that don't belong in our world and don't mix well with nature. Discarded plastics are a big cause of pollution, cluttering rivers, seas, and beaches, killing fish, choking birds, and making our environment a much less attractive place. Public pressure to clean up has produced plastics that seem to be more environmentally friendly. But are they all they're cracked up to be?

The global plastics problem

Plastics are carbon-based polymers (long-chain molecules that repeat their structures over and over) and we make them mostly from petroleum. They're incredibly versatile—by definition: the word plastic, which means flexible, says it all. The trouble is that plastic is just too good. We use it for mostly disposable, low-value items such as food-wrap and product packaging, but there's nothing particularly disposable about most plastics. On average, we use plastic bags for 12 minutes before getting rid of them, yet they can take fully 500 years to break down in the environment (quite how anyone knows this is a mystery, since plastics have been around only about a century).

Getting rid of plastics is extremely difficult. Burning them can give off toxic chemicals such as dioxins, while collecting and recyclingthem responsibly is also difficult, because there are many different kinds and each has to be recycled by a different process. If we used only tiny amounts of plastics that wouldn't be so bad, but we use them in astounding quantities. In Britain alone (one small island in a very big world), people use 8 billion disposable plastic bags each year. If you've ever taken part in a beach clean, you'll know that about 80 percent of the waste that washes up on the shore is plastic, including bottles, bottle tops, and tiny odd fragments known as "mermaids' tears."

We're literally drowning in plastic we cannot get rid of. And we're making most of it from oil—a non-renewable resource that's becoming increasingly expensive. It's been estimated that 200,000 barrels of oil are used each day to make plastic packaging for the United States alone.

Making better plastics

Photo: Plastics can begin to photodegrade quite quickly, but they take a very long time to break down completely. The old grocery store bag on the left has been exposed to the light for a few months and has already started to turn yellow (compared to the new bag on the right).

Ironically, plastics are engineered to last. You may have noticed that some plastics do, gradually, start to go cloudy or yellow after long exposure to daylight (more specifically, in the ultraviolet light that sunlight contains). To stop this happening, plastics manufacturers generally introduce extra stabilizing chemicals to give their products longer life. With society's ever-increasing focus on protecting the environment, there's a new emphasis on designing plastics that will disappear much more quickly.

Broadly speaking, so-called "environmentally friendly" plastics fall into three types:

· Bioplastics made from natural materials such as corn starch

· Biodegradable plastics made from traditional petrochemicals, which are engineered to break down more quickly

· Eco/recycled plastics, which are simply plastics made from recycled plastic materials rather than raw petrochemicals.

Bioplastics

Photo: Some bioplastics can be harmlessly composted. Others leave toxic residues or plastic fragments behind, making them unsuitable for composting if your compost is being used to grow food.

The theory behind bioplastics is simple: if we could make plastics from kinder chemicals to start with, they'd break down more quickly and easily when we got rid of them. The most familiar bioplastics are made from natural materials such as corn starch and sold under such names as EverCorn™ and NatureWorks—with a distinct emphasis on environmental credentials. Some bioplastics look virtually indistinguishable from traditional petrochemical plastics. Polylactide acid (PLA)looks and behaves like polyethylene and polypropylene and is now widely used for food containers. According to NatureWorks, making PLA saves two thirds the energy you need to make traditional plastics. Unlike traditional plastics and biodegradable plastics, bioplastics generally do not produce a net increase in carbon dioxide gas when they break down (because the plants that were used to make them absorbed the same amount of carbon dioxide to begin with). PLA, for example, produces almost 70 percent less greenhouse gases when it degrades in landfills.

Another good thing about bioplastics is that they're generally compostable: they decay into natural materials that blend harmlessly with soil. Some bioplastics can break down in a matter of weeks. The cornstarch molecules they contain slowly absorb water and swell up, causing them to break apart into small fragments that bacteria can digest more readily. Unfortunately, not all bioplastics compost easily or completely and some leave toxic residues or plastic fragments behind. Some will break down only at high temperatures in industrial-scale, municipal composters or digesters, or in biologically active landfills (also called bioreactor landfills), not on ordinary home compost heaps or in conventional landfills. There are various eco-labeling standards around the world that spell out the difference between home and industrial composting and the amount of time in which a plastic must degrade in order to qualify.

Biodegradable plastics

If you're in the habit of reading what supermarkets print on their plastic bags, you may have noticed a lot of environmentally friendly statements appearing over the last few years. Some stores now use what are described as photodegradable, oxydegradable (also called oxodegradable or PAC, Pro-oxidant Additive Containing, plastic), or just biodegradable bags (in practice, whatever they're called, it often means the same thing). As the name suggests, these biodegradable plastics contain additives that cause them to decay more rapidly in the presence of light and oxygen (moisture and heat help too). Unlike bioplastics, biodegradable plastics are made of normal (petrochemical) plastics and don't always break down into harmless substances: sometimes they leave behind a toxic residue and that makes them generally (but not always) unsuitable for composting.

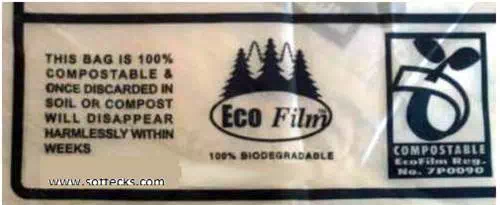

Photo: A typical message on a biodegradable bag. This one, made from Eco Film™,

is compostable too.

Biodegradable bags sound great, but they're not without their problems. In 2014, for example, some members of the European Parliament tried hard to bring about a complete ban on oxydegradable plastics in the EU, with growing doubts over their environmental benefits. Although that proposal was blocked, it lead to more detailed studies of oxydegradable plastics, apparently confirming that they can't be effectively composted or anaerobically digested and don't usually break down in landfills. In the oceans, the water is usually too cold to break down biodegradable plastics, so they either float forever on the surface (just like conventional plastics) or, if they do break down, produce tiny plastic fragments that are harmful to marine life.

Recycled plastics

One neat solution to the problem of plastic disposal is to recycle old plastic materials (like used milk bottles) into new ones (such as items of clothing). A product called ecoplastic is sold as a replacement for wood for use in outdoor garden furniture and fence posts. Made from high-molecular polyethylene, the manufacturers boast that it's long-lasting, attractive, relatively cheap, and nice to look at.

Photo: This "wooden" public bench looks much like any other until you look at the grain really closely. Then you can see the wood is actually recycled plastic. The surface texture is convincing, but the giveaway is the ends of the "planks," which don't look anything like the grain of wood. But there are two problems with recycled plastics. First, plastic that's recycled is generally not used to make the same items the next time around: old recycled plastic bottles don't go to make new plastic bottles, but lower-grade items such as plastic benches and fence posts. Second, you can't automatically assume recycled plastics are better for the environment unless you know they've been made with a net saving of energy and water, a net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, or some other overall benefit to the environment. Keeping waste out of a landfill and turning it into new things is great, but what if it takes a huge amount of energy to collect and recycle the plastic—more even than making brand new plastic products?

Are bioplastics good or bad?

Anything that helps humankind solve the plastics problem has to be a good thing, right? Unfortunately, environmental issues are never quite so simple. Actions that seem to help the planet in obvious ways sometimes have major drawbacks and can do damage in other ways. It's important to see things in the round to understand whether "environmentally friendly" things are really doing more harm than good.

Bioplastics and biodegradable plastics have long been controversial. Manufacturers like to portray them as a magic-bullet solution to the problem of plastics that won't go away. Bioplastics, for example, are touted as saving 30–80 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions you'd get from normal plastics and they can give food longer shelf-life in stores. But here are some of the drawbacks:

· When some biodegradable plastics decompose in landfills, they produce methane gas. This is a very powerful greenhouse gas that adds to the problem of global warming.

· Biodegradable plastics and bioplastics don't always readily decompose. Some need exposure to UV (ultraviolet) light or relatively high temperatures and, in some conditions, can still take many years to break down. Even then, they may leave behind micro-fragments or toxic residues.

· Bioplastics are made from plants such as corn and maize, so land that could be used to grow food for the world is being used to "grow plastic" instead. By 2014, almost a quarter of US grain production was expected to have been turned over to biofuels and bioplastics production; taking more agricultural land out of production could cause a significant rise in food prices that would hit poorest people hardest.

· Growing crops to make bioplastics comes with the usual environmental impacts of intensive agriculture, including greenhouse emissions from the petroleum needed to fuel farm machinery, and water pollution caused by runoff from land where fertilizers are used in industrial quantities. In some cases, these indirect impacts from "growing" bioplastics are greater than if we simply made plastics from petroleum in the first place.

· Some bioplastics, such as PLA, are made from genetically modified corn. Some environmentalists consider GM (genetically modified) crops to be inherently harmful to the environment, though others disagree.

· Bioplastics and biodegradable plastics cannot be easily recycled. To most people, PLA looks very similar to PET (polyethylene terephthalate) but, if the two are mixed up in a recycling bin, the whole collection becomes impossible to recycle. There are fears that increasing use of PLA may undermine existing efforts to recycle plastics.

· Many people think terms like "bioplastic," "biodegradable," and "compostable" mean exactly the same thing. But there's a huge difference between a "biodegradable" plastic (one that might take decades or centuries to break down) and a truly "compostable" material (something that turns almost entirely into benign waste after a matter of months in a composter), while "bioplastic," as we've already seen, can also mean different things. Confusing jargon hampers public understanding, which makes it harder for consumers to grasp the issues and make positive choices when they shop.

How to cut down on plastics

Why is life never simple? If you're keen on helping the planet, complications like this sound completely exasperating. But don't let that put you off. As many environmental campaigners point out, there are some very simple solutions to the plastics problem that everyone can bear in mind to make a real difference. Instead of simply sending your plastics waste for recycling, remember the saying "Reduce, repair, reuse, recycle". Recycling, though valuable, is only slightly better than throwing something away: you still have to use energy and water to recycle things and you probably create toxic waste products as well. It's far better to reduce our need for plastics in the first place than to have to dispose of them afterwards.

Photo: Recycling only works if it's economically viable. You can help create a market for recycled products by actively choosing them over alternatives. This Bic Evolution pencil, for example, is made from 57 percent recycled plastic, which is a mixture of pre-consumer waste (a waste product from another industry) and post-consumer waste (recycled household and office material).

You can make a positive difference by actively cutting down on the plastics you use. For example:

· Get a reusable cotton bag and take that with you ever time you go shopping.

· Buy your fruit and vegetables loose, avoiding the extra plastic on pre-packaged items.

· Use long-lasting items (such as razors and refillable pens) rather than disposable ones. It can work out far cheaper in the long run.

· If you break something, can you repair it simply and carry on using it? Do you really have to buy a new one?

· Can you give unwanted plastic items a new lease of life? Ice cream tubs make great storage containers; vending machine cups can be turned into plant pots; and you can use old plastic supermarket bags for holding your litter.

· When you do have to buy new things, why not buy ones made from recycled materials? By helping to create a market for recycled products, you encourage more manufacturers to recycle.