Storage tank fire protection

Storage tank fire protection and prevention is a specialized science which depends on the interrelationship of tank type, condition and size; product and amount stored in the tank; tank spacing, dyking and drainage; facility fire protection and response capabilities; outside assistance; and company philosophy, industry standards and government regulations. Storage tank fires may be easy or very difficult to control and extinguish, depending primarily on whether the fire is detected and attacked during its initial inception. Storage tank operators should refer to the numerous recommended practices and standards developed by organizations such as the American Petroleum Institute (API) and the US National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), which cover storage tank fire prevention and protection in great detail.

If open-top floating roof storage tanks are out of round or if the seals are worn or not tight against the tank shells, vapours can escape and mix with air, forming flammable mixtures. In such situations, when lightning strikes, fires may occur at the point where the roof seals meet the shell of the tank. If detected early, small seal fires can often be extinguished by a hand-carried dry powder extinguisher or with foam applied from a foam hose or foam system.

If a seal fire cannot be controlled with hand extinguishers or hose streams, or if a large fire is in progress, foam may be applied onto the roof through fixed or semi-fixed systems or by large foam monitors. Precautions are necessary when applying foam onto the roofs of floating roof tanks; if too much weight is placed on the roof, it may tilt or sink, allowing a large surface area of product to be exposed and become involved in the fire. Foam dams are used on floating roof tanks to trap foam in the area between the seals and the tank shell. As the foam settles, water drains out under the foam dams and should be removed through the tank roof drain system to avoid overweighing and sinking the roof.

Depending on government regulations and company policy, storage tanks may be provided with fixed or semi-fixed foam systems which include: piping to the tanks, foam risers and foam chambers on the tanks; subsurface injection piping and nozzles inside the bottom of tanks; and distribution piping and foam dams on the tops of tanks.With fixed systems, foam-water solutions are generated in centrally located foam houses and pumped to the tank through a piping system. Semi-fixed foam systems typically use portable foam tanks, foam generators and pumps which are brought to the tank involved, connected to a water supply and connected to the tank’s foam piping.

Water-foam solutions may also be centrally generated and distributed within the facility through a system of piping and hydrants, and hoses would be used to connect the nearest hydrant to the tank’s semi-fixed foam system. Where tanks are not provided with fixed or semi-fixed foam systems, foam may be applied onto the tops of tanks, using foam monitors, fire hoses and nozzles. Regardless of the method of application, in order to control a fully involved tank fire, a specific amount of foam must be applied using special techniques at a specific concentration and rate of flow for a minimum amount of time depending primarily on the size of the tank, the product involved and the surface area of the fire. If there is not enough foam concentrate available to meet the required application criteria, the possibility of control or extinguishment is minimal.

Only trained and knowledgeable fire-fighters should be allowed to use water to fight liquid petroleum tank fires. Instantaneous eruptions, or boil-overs, can occur when water turns into steam upon direct application onto tank fires involving crude or heavy petroleum products. As water is heavier than most hydrocarbon fuels, it will sink to the bottom of a tank and, if enough is applied, fill the tank and push the burning product up and over the top of the tank.

Water is typically used to control or extinguish spill fires around the outside of tanks so that valves can be operated to control product flow, to cool the sides of involved tanks to prevent boiling liquid–expanding vapour explosions (BLEVEs—see the section “Fire hazards of LHGs” below) and to reduce the effect of heat and flame impingement on adjacent tanks and equipment. Because of the need for specialized training, materials and equipment, rather than allow employees to attempt to extinguish tank fires, many terminals and bulk plants have established a policy to remove as much product as possible from the involved tank, protect adjacent structures from heat and flame and allow the remaining product in the tank to burn under controlled conditions until the fire burns out.

Terminal and bulk plant health and safety

Storage tank foundations, supports and piping should be regularly inspected for corrosion, erosion, settling or other visible damage to prevent loss or degradation of product. Tank pressure/vacuum valves, seals and shields, vents, foam chambers, roof drains, water draw-off valves and overfill detection devices should be inspected, tested and maintained on a regular schedule, including removal of ice in the winter. Where flame arrestors are installed on tank vents or in vapour recovery lines, they have to be inspected and cleaned regularly and kept free of frost in the winter to ensure proper operation. Valves on tank outlets which close automatically in case of fire or drop in pressure should be checked for operability.

Dyke surfaces should drain or slope away from tanks, pumps and piping to remove any spilled or released product to a safe area. Dyke walls should be maintained in good condition, with drain valves kept closed except when draining water and dyke areas excavated as needed to maintain design capacity. Stairways, ramps, ladders, platforms and railings to loading racks, dykes and tanks should be maintained in a safe condition, free of ice, snow and oil. Leaking tanks and piping should be repaired as soon as possible. The use of victaulic or similar couplings on piping within dyked areas which could be exposed to heat should be discouraged to prevent lines from opening during fires.

Safety procedures and safe work practices should be established and implemented, and training or education provided, so that terminal and bulk plant operators, maintenance personnel, tank truck drivers and contractor personnel can work safely. These should include, as a minimum, information concerning the basics of hydrocarbon fire ignition, control and extinguishment; hazards and protection from exposures to toxic substances such as hydrogen sulphide and polynuclear aromatics in crude oil and residual fuels, benzene in gasoline and additives such as tetraethyl lead and methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE); emergency response actions; and normal physical and climatic hazards associated with this activity.

Asbestos or other insulation may be present in the facility as protection for tanks and piping. Appropriate safe-work and personal protective measures should be established and followed for handling, removing and disposing of such materials.

Environmental protection

Terminal operators and employees should be aware of and comply with government regulations and company policies covering environmental protection of ground and surface water, soil and air from pollution by petroleum liquids and vapours, and for handling and removing hazardous waste.

- Water contamination. Many terminals have oil/water separators to handle contaminated water from tank containment areas, run-off from loading racks and parking areas and water drained from tanks and open-top tank roofs. Terminals may be required to meet established water quality standards and obtain permits before discharging water.

- Air pollution. Air pollution prevention includes minimizing releases of vapours from valves and vents. Vapour recovery units collect vapours from loading racks and marine docks, even when tanks are vented prior to entry. These vapours are either processed and returned to storage as liquids or burned.

- Spills on land and water. Government agencies and companies may require that oil storage facilities have spill prevention control and counter-measure plans, and that personnel be trained and aware of the potential hazards, notifications to be made and the actions to take in case of a spill or release. In addition to handling spills within the terminal facility, personnel are often trained and equipped to respond to offsite emergencies, such as a tank truck rollover.

- Sewage and hazardous waste. Terminals may be required to meet regulatory requirements and obtain permits for discharge of sewage and oily waste to public or privately owned treatment works. Various government requirements and company procedures may apply to the onsite storage and handling of hazardous waste such as asbestos insulation, tank cleaning residue and contaminated product. Workers should be trained in this activity and be made aware of the potential hazards from exposures which could occur.

LHG Storage and Handling

Bulk storage tanks

LHGs are stored in large bulk storage tanks at the point of process (gas and oil fields, gas plants and refineries) and at the point of distribution to the consumer (terminals and bulk plants). The two most commonly used methods of bulk storage of LHGs are:

- Under high pressure at ambient temperature. LHG is stored in steel pressure tanks (at 1.6 to 1.8 mPa) or in underground impermeable rock or salt formations.

- Under pressure close to atmospheric at low temperature. LHG is stored in thin-walled, heat-insulated steel storage tanks; in reinforced concrete tanks above and below ground; and in underground cryogenic storage tanks. Pressure is maintained close to atmospheric (0.005 to 0.007 mPa) at a temperature of –160°C for LNG stored in cryogenic underground storage tanks.

LPG bulk storage vessels are either cylindrically (bullet) shaped horizontal tanks (40 to 200 m3) or spheres (up to 8,000 m3). Refrigerated storage is typical for storage in excess of 2,400 m3. Both horizontal tanks, which are fabricated in shops and transported to the storage site, and spheres, which are built onsite, are designed and constructed in accordance with rigid specifications, codes and standards.

The design pressure of storage tanks should not be less than the vapour pressure of the LHG to be stored at the maximum service temperature. Tanks for propane-butane mixtures should be designed for 100% propane pressure. Consideration should be given to additional pressure requirements resulting from the hydrostatic head of the product at maximum fill and the partial pressure of non-condensible gases in the vapour space. Ideally, liquefied hydrocarbon gas storage vessels should be designed for full vacuum. If not, vacuum relief valves must be provided. Design features should also include pressure relief devices, liquid level gauges, pressure and temperature gauges, internal shut-off valves, back flow preventers and excess flow check valves. Emergency fail-safe shut-down valves and high level signals may also be provided.

Horizontal tanks are either installed aboveground, placed on mounds or buried underground, typically downwind from any existing or potential sources of ignition. If the end of a horizontal tank ruptures from over-pressurization, the shell will be propelled in the direction of the other end. Therefore, it is prudent to place an aboveground tank so that its length is parallel to any important structure (and so that neither end points toward any important structure or equipment). Other factors include tank spacing, location, and fire prevention and protection. Codes and regulations specify minimum horizontal distances between pressurized liquefied hydrocarbon gas storage vessels and adjoining properties, tanks and important structures as well as potential sources of ignition, including processes, flares, heaters, power transmission lines and transformers, loading and unloading facilities, internal combustion engines and gas turbines.

Drainage and spill containment are important considerations in designing and maintaining liquid hydrocarbon gas tank storage areas in order to direct spills to a location where they will minimize risk to the facility and surrounding areas. Dyking and impounding may be used where spills present a potential hazard to other facilities or to the public. Storage tanks are not usually dyked, but the ground is graded so that vapours and liquids do not collect underneath or around the storage tanks, in order to keep burning spills from impinging upon storage tanks.

Cylinders

LHGs for use by consumers, either LNG or LPG, are stored in cylinders at temperatures above their boiling points at normal temperature and pressure. All LNG and LPG cylinders are provided with protective collars, safety valves and valve caps. The basic types of consumer cylinders in use are:

- vapour withdrawal (1/2 to 50 kg) cylinders used by consumers, with larger ones usually refillable on an exchange basis with the supplier

- liquid withdrawal cylinders for dispensing into small consumer-owned refillable cylinders

- motor vehicle fuel cylinders, including vehicle cylinders (40 kg) permanently installed as fuel tanks on motor vehicles and filled and used in the horizontal position, and industrial truck cylinders designed to be stored, filled and handled in the upright position, but used in the horizontal position.

Properties of hydrocarbon gases

According to the NFPA, flammable (combustible) gases are those which burn in the normal concentrations of oxygen in air. The burning of flammable gases is similar to flammable hydrocarbon liquid vapours, as a specific ignition temperature is needed to initiate the burning reaction, and each will burn only within a certain defined range of gas-air mixtures. Flammable liquids have a flashpoint, which is the temperature (always below the boiling point) at which they emit sufficient vapours for combustion. There is no apparent flashpoint for flammable gases, since they are normally at temperatures above their boiling points, even when liquefied, and are therefore always at temperatures well in excess of their flashpoints.

The NFPA (1976) defines compressed and liquefied gases as follows:

- “Compressed gases are those which at all normal atmospheric temperatures inside their containers, exist solely in the gaseous state under pressure.”

- “Liquefied gases are those which at normal atmospheric temperatures inside their containers, exist partly in the liquid state and partly in the gaseous state, and are under pressure as long as any liquid remains in the container.”

The major factor which determines the pressure inside the vessel is the temperature of the liquid stored. When exposed to the atmosphere, the liquefied gas very rapidly vaporizes, travelling along the ground or water surface unless dispersed into the air by wind or mechanical air movement. At normal atmospheric temperatures, about one-third of the liquid in the container will vaporize. Flammable gases are further classified as fuel gas and industrial gas. Fuel gases, including natural gas (methane) and LPGs (propane and butane), are burned with air to produce heat in ovens, furnaces, water heaters and boilers. Flammable industrial gases, such as acetylene, are used in processing, welding, cutting and heat-treating operations. The differences in combustion properties of LNG and LPGs are shown in table 1.

Table 1. Typical approximate combustion properties of liquified hydrocarbon gases.

|

Type gas |

Flammable range |

Vapour pressure |

Normal init. boiling |

Weight (pounds/gal) |

BTU per ft3 |

Specific gravity |

|

LNG |

4.5–14 |

1.47 |

–162 |

3.5–4 |

1,050 |

9.2–10 |

|

LPG (propane) |

2.1–9.6 |

132 |

–46 |

4.24 |

2,500 |

1.52 |

|

LPG (butane) |

1.9–8.5 |

17 |

–9 |

4.81 |

3,200 |

2.0 |

Safety hazards of LPG and LNG

The safety hazards applicable to all LHGs are associated with flammability, chemical reactivity, temperature and pressure. The most serious hazard with LHGs is the unplanned release from containers (canisters or tanks) and contact with an ignition source. Release can occur by failure of the container or valves for a variety of reasons, such as overfilling a container or from overpressure venting when the gas expands due to heating.

The liquid phase of LPG has a high coefficient of expansion, with liquid propane expanding 16 times and liquid butane 11 times as much as water with the same rise in temperature. This property must be considered when filling containers, as free space must be left for the vapour phase. The correct quantity to be filled is determined by a number of variables, including the nature of the liquefied gas, temperature at time of filling and expected ambient temperatures, size, type (insulated or uninsulated) and location of container (above or below ground). Codes and regulations establish allowable quantities, known as “filling densities”, which are specific for individual gases or families of similar gases. Filling densities may be expressed by weight, which are absolute values, or by liquid volume, which must always be temperature corrected.

The maximum amount that LPG pressure containers should be filled with liquid is 85% at 40 ºC (less at higher temperatures). Because LNG is stored under low temperatures, LNG containers may be liquid filled from 90% to 95%. All containers are provided with overpressure relief devices which normally discharge at pressures relating to liquid temperatures above normal atmospheric temperatures. As these valves cannot reduce the internal pressure to atmospheric, the liquid will always be at a temperature above its normal boiling point. Pure compressed and liquefied hydrocarbon gases are non-corrosive to steel and most copper alloys. However, corrosion can be a serious problem when sulphur compounds and impurities are present in the gas.

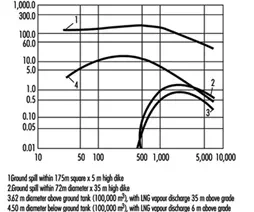

LPGs are 1-1/2 to 2 times heavier than air and, when released in air, tend to quickly disperse along the ground or water surface and collect in low areas. However, as soon as the vapour is diluted by air and forms a flammable mixture, its density is essentially the same as air, and it disperses differently. Wind will significantly reduce the dispersion distance for any size of leak. LNG vapours react differently from LPG. Because natural gas has a low vapour density (0.6), it will mix and disperse rapidly in open air, reducing the chance of forming a flammable mixture with air. Natural gas will collect in enclosed spaces and form vapour clouds which could be ignited. Figure 4 indicates how a liquefied natural gas vapour cloud spreads downwind in different spill situations.

Figure 4. Extension of LNG vapour cloud downwind from different spills (wind speed 8.05 km/h).

Although LHG is colourless, when released in air its vapours will be noticeable due to the condensation and freezing of water vapour contained in the atmosphere which is contacted by the vapour. This may not occur if the vapour is near ambient temperature and its pressure is relatively low. Instruments are available which can detect the presence of leaking LHG and signal an alarm at levels as low as 15 to 20% of the lower flammable limit (LFL). These devices may also stop all operations and activate suppression systems, should the concentrations of gas reach 40 to 50% of the LFL. Some industrial operations provide forced ventilation to keep leaking fuel-air concentrations below the lower flammable limit. Heater and furnace burners may also have devices which automatically stop the flow of gas if the flame is extinguished. LHG leakage from tanks and containers may be minimized by the use of limiting and flow control devices. When decompressed and released, LHG will flow out of containers with a low negative pressure and low temperature. The auto refrigeration temperature of the product at the lower pressure must be considered when selecting materials of construction for containers and valves, to prevent metal embrittlement followed by rupture or failure due to exposure to low temperatures.

LHG can contain water in both its liquid and gaseous phases. Water vapour can saturate gas in a specific amount at a given temperature and pressure. If the temperature or pressure changes, or the water vapour content exceeds the evaporation limits, the water condenses. This can create ice plugs in valves and regulators and form hydrocarbon hydrate crystals in pipelines, devices and other apparatus. These hydrates can be decomposed by heating the gas, lowering the gas pressure or introducing materials, such as methanol, which reduce the water vapour pressure.

There are differences in the characteristics of compressed and liquefied gases which must be considered from safety, health and fire aspects. As an example, the differences in the characteristics of compressed natural gas and LNG are illustrated in table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of characteristics of compressed and liquified gas.

|

Type gas |

Flammable

range |

Heat release rate (BTU/gal) |

Storage condition |

Fire risks |

Health risks |

|

Compressed natural gas |

5.0–15 |

19,760 |

Gas at 2,400 to 4,000 psi |

Flammable gas |

Asphyxiant; overpressure |

|

LNG |

4.5–14 |

82,450 |

Liquid at 40–140 psi |

Flammable gas 625:1 expansion ratio; BLEVE |

Asphyxiant; cryogenic liquid |

Health hazards of LHGs

The primary occupational injury concern in handling LHGs is the potential hazard of frostbite to the skin and eyes from contact with liquid during handling and storage activities including sampling, measuring, filling, receiving and delivery. As with other fuel gases, when improperly burned, compressed and liquefied hydrocarbon gases will emit undesirable levels of carbon monoxide. Under atmospheric pressures and low concentrations, compressed and liquefied hydrocarbon gases are normally non-toxic, but they are asphyxiants—they will displace oxygen (air) if released in enclosed or confined spaces. Compressed and liquefied hydrocarbon gases may be toxic if they contain sulphur compounds, especially hydrogen sulphide. Because LHGs are colourless and odourless, safeguards include adding odourants, such as mercaptans, to consumer fuel gases to aid in leak detection. Safe work practices should be implemented to protect workers from exposure to mercaptans and other additives during storage and injection. Exposure to LPG vapours in concentrations at or above the LFL may cause a general central nervous system depression similar to anaesthesia gases or intoxicants.

Fire hazards of LHGs

Failure of liquefied gas (LNG and LPG) containers constitutes a more severe hazard than failure of compressed gas containers, as they release greater quantities of gas. When heated, liquefied gases react differently from compressed gases, because they are two-phase (liquid-vapour) products. As the temperature rises, the vapour pressure of the liquid is increased, resulting in increased pressure inside the container. The vapour phase first expands, followed by expansion of the liquid, which then compresses the vapour. The design pressure for LHG vessels is therefore assumed to be near that of the gas pressure at maximum possible ambient temperature.

When a liquefied gas container is exposed to fire, a serious condition can occur if the metal in the vapour space is allowed to heat. Unlike the liquid phase, the vapour phase absorbs little heat. This allows the metal to heat rapidly until a critical point is reached at which an instantaneous, catastrophic explosive failure of the container occurs. This phenomenon is known as a BLEVE. The magnitude of a BLEVE depends on the amount of liquid vaporizing when the container fails, the size of the pieces of exploded container, the distance they travel and the areas they impact. Uninsulated LPG containers may be protected against a BLEVE by applying cooling water to those areas of the container which are in the vapour phase (not in contact with LPG).

Other more common fire hazards associated with compressed and liquefied hydrocarbon gases include electrostatic discharge, combustion explosions, large open-air explosions and small leaks from pump seals, containers, valves, pipes, hoses and connections.

- Electrostatic charges may be generated when LHG is shipped in pipelines, when loaded and unloaded, in blending and filtering and during tank cleaning.

- Combustion explosions result when escaping gas or vapour is contained in a confined space or structure and combines with air to create a flammable mixture. When this flammable mixture contacts a source of ignition, it burns instantaneously and rapidly, producing extreme heat. The very hot air expands quickly, causing a considerable rise in pressure. If the space or structure is not strong enough to contain this pressure, a combustion explosion occurs.

- Flammable gas fires result when there is no confinement of the escaping gas or vapours, or ignition occurs when only a small amount of gas has been released.

- Large open-air explosions occur when a massive failure of a container releases a large vapour cloud of gas which is ignited before it disperses.

Controlling sources of ignition in hazardous areas is essential for the safe handling of compressed and liquefied hydrocarbon gases. This may be accomplished by establishing a permit system to authorize and control hot work, smoking, operation of motor vehicles or other internal combustion engines, and the use of open flames in areas where compressed and liquefied hydrocarbon gas is transported, stored and handled. Other safeguards include the use of properly classified electrical equipment and bonding and grounding systems to neutralize and dissipate static electricity. The best means of reducing the fire hazard of leaking compressed or liquefied hydrocarbon gas is to stop the release, or shut off the flow of product, if possible. Although most LHGs will vaporize upon contact with air, lower vapour pressure LPGs, such as butane, and even some higher vapour pressure LPGs, such as propane, will pool if ambient temperatures are low. Water should not be applied to these pools, as it will create turbulence and increase the rate of vaporization. Vaporization from pool spills can be controlled by the careful application of foam. Water, if correctly applied against a leaking valve or small rupture, can freeze upon contact with the cold LHG and block the leak. LHG fires require controlling heat impingement upon storage tanks and containers by the application of cooling water. While compressed and liquefied hydrocarbon gas fires can be extinguished by the use of water spray and dry powder extinguishers, it is often more prudent to allow controlled burning so that a combustible explosive vapour cloud does not form and re-ignite should the gas continue to escape after the fire is extinguished.