Bacteria lead the way to more efficient oil production

Biota, a California startup, is developing a means of improving oil and gas operations by analyzing the bacteria that emerge from the wellhead.

In the rocky depths of the nation’s shale oil fields, thousands of feet below the production frenzy, primordial bacteria subsist on the very hydrocarbons that make up oil and gas and have transformed the U.S. into an energy powerhouse rivaling Saudi Arabia and Russia.

The microbes are among the least-studied life forms on earth, emerging to the surface as anonymous organisms thought to have evolved within the harsh extremes of the subsurface over hundreds of millions of years. Oil and gas producers for decades paid them limited attention — until a cutting-edge startup recognized their potential to help produce oil and gas even more efficiently.

Now, as industry competition intensifies, a growing number of producers have partnered with Biota, a startup developing the means of achieving that goal by analyzing the bacteria that emerge from the wellhead. More than 20 producers in the Permian Basin and elsewhere have shipped rock and fluid samples to the company’s San Diego lab, intrigued by the promise of data that could help them drill more precisely, lower production costs and boost profits.

Think of it as biotechnology meets petroleum engineering. Unique microbial colonies reside within the various layers, cracks and faults in any given oil basin, making it possible to discern the boundaries of deep underground formations by analyzing the DNA of the bacteria within them. In the Permian, for example, bacteria in two overlapping layers — the Bone Spring and the Wolfcamp — are biologically distinct, providing markers that could determine whether a well is drawing from one source or the other during the course of operations.

That’s critical information for drillers trying to make the best use of each well. Right now, if a company drills two wells, one targeting the Bone Spring, the other the Wolfcamp, it is challenged to know for sure if those wells are drawing from their intended targets. Both wells could be sucking oil from, say, the Bone Spring, depleting that source more quickly while missing out on the crude from the Wolfcamp.

Biota CEO Ajay Kshatriya, a chemical engineer who grew up in Katy and spent much of his career in California’s biotech industry, compares oilfield acreage to a six-pack of soda, each can a distinct formation or reservoir. The producer aims to place one straw in each can, but sometimes, two straws wind up in the same can, doubling the company’s cost to produce what could have been done with one. And there’s the chance that some cans will remain unopened, leaving profits underground.

“By understanding the boundaries of those cans,” Kshatriya said, “you know where to put the wells.”

For all of their advanced technology — seismic imaging, computer models and production monitors — energy companies still can’t be certain where oil and gas is coming from once the shale rock is shattered through hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. It’s like throwing a rock at a window; even with perfect planning and aim, the cracks will zig-zag unpredictably in any direction. It becomes even more unpredictable thousands of feet below ground.

That’s where the bacteria, among the earth’s oldest organisms, come in. Over the eons, the bacteria adapted to particular conditions underground, diversifying genetically into different strains depending on heat, pressure and other conditions in the mishmash of prehistoric sediment overlapping in different formations. In other words, the strains of bacteria in the Wolfcamp have a different genetic makeups than those in the Bone Spring.

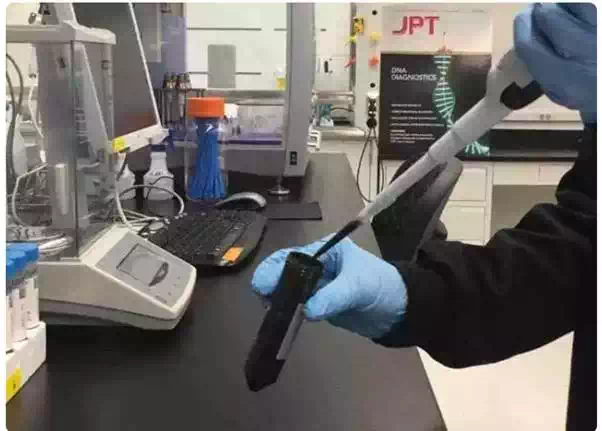

Biota, which has offices in California and Houston, uses DNA sequencing, computer algorithms and a proprietary database to identify the strains of bacteria that come up through oil and gas wells and maps those microbes to their respective formations based on where the samples were taken. Drawing on more than 20,000 samples from some 500 wells in the Permian and nine other basins, Biota has analyzed more than 400 million DNA sequences from the nation’s most prolific production areas, and recently began working with offshore customers in the Gulf of Mexico and Asia.

As the map becomes more extensive and detailed, oil and gas companies would be able to confirm the source of crude — and adjust operations as needed — with information about the bacteria produced from the well. It’s another tool for an industry than can no longer count on $100 a barrel oil to cover cost overruns, especially as investors increase pressure to keep a lid on costs and boost profits.

Marathon Oil and EP Energy of Houston and Anadarko Petroleum of The Woodlands have signed on with Biota, as have Norway’s Equinor and Australia’s BHP Billiton, among others. Recently, Midland’s Concho Resources, Pennsylvania’s EQT Resources and Malaysia’s Petronas joined the customer roster.

John Gibson, chairman of energy technology at Houston energy investment bank Tudor Pickering Holt & Co., has worked for the past year to connect Biota with the bank’s oil and gas clients, extolling the insights expected to come when the company has analyzed enough bacterial DNA to map wide production areas. The bank has not invested in Biota.

“The more we know about the bacteria, the more we know about the reservoir,” Gibson said. “There is enormous potential here.”

For oil and gas companies, the data has the potential to show far more than how a single well performs once it’s fracked. Data from multiple wells could determine how they interact and help producers find the optimal number of wells to develop a reservoir. And it could enable them to monitor production over time — a well that starts off siphoning oil from the Wolfcamp, for example, could, at some point, begin to draw from a different formation.