Where Our Oil Comes From

The United States is one of the largest crude oil producers

U.S. refineries obtain crude oil produced in the United States and in other countries. Different types of companies supply crude oil to the world market.

Where is U.S. crude oil produced?

Crude oil is produced in 32 U.S. states and in U.S. coastal waters. In 2017, about 65% of total U.S. crude oil production came from five states:

· Texas—38%

· North Dakota—11%

· Alaska—5%

· California—5%

· New Mexico—5%

In 2017, about 18% of U.S. crude oil was produced from wells located offshore in the federally administered waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Although total U.S. crude oil production generally declined between 1985 and 2008, annual production increased from 2009 through 2015. Production declined slightly in 2016 and increased in 2017. More cost-effective drilling technology helped to boost production, especially in Texas, North Dakota, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Colorado.

Many countries produce crude oil

About 100 countries produce crude oil. In 2017, 48% of the world's total crude oil production came from five countries:

· Russia—13%

· Saudi Arabia—13%

· United States—12%

· Iraq—6%

· Iran—5%

Different types of oil companies supply crude oil

The world oil market is complex. Governments and private companies play various roles in moving crude oil from producers to consumers. In the United States, companies produce crude oil on private and public land and offshore waters. Most of these companies are independent producers, and they usually operate only in the United States. The other companies, often referred to as major oil companies, may have hundreds or thousands of employees and operate in many countries. Examples of major U.S. oil companies are Chevron and ExxonMobil. Three types of companies supply crude oil to the global oil market. Each type of company has different operational strategies and production-related goals.

International oil companies

International oil companies (IOCs) companies, which include ExxonMobil, BP, and Royal Dutch Shell, are entirely investor owned and are primarily interested in increasing their shareholder value. As a result, IOCs tend to make investment decisions based on economic factors. IOCs typically move quickly to develop and produce the oil resources available to them and sell their output in the global market. Although these producers must follow the laws of the countries in which they produce oil, all of their decisions are ultimately made in the interest of the company and its shareholders, not in the interest of a government.

National oil companies

National oil companies (NOCs) operate as extensions of a government or a government agency, and they include companies such as Saudi Aramco (Saudi Arabia), Pemex (Mexico), the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), and Petroleos de Venezuela S.A. (PdVSA). NOCs financially support government programs and sometimes provide strategic support. NOCs often provide fuels to their domestic consumers at a lower price than the fuels they provide to the international market. They do not always have the incentive, means, or intention to develop their reserves at the same pace as investor-owned international oil companies. Because of the diverse objectives of their supporting governments, NOCs pursue goals that are not necessarily market oriented. The goals of NOCs often include employing citizens, furthering a government's domestic or foreign policies, generating long-term revenue to pay for government programs, and supplying inexpensive domestic energy. All NOCs that belong to members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) fall into this category.

NOCs with strategic and operational autonomy

The NOCs in this category function as corporate entities and do not operate as extensions of their countries' governments. This category includes Petrobras (Brazil) and Statoil (Norway). These companies often balance profit-oriented concerns and the objectives of their countries with the development of their corporate strategies. Although these companies are driven by commercial concerns, they may also take into account their nations' goals when making investment or other strategic decisions.

OPEC members have a large share of world oil supplies

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is a group that includes some of the world's most oil-rich countries (see list of OPEC member countries at right). Together, these countries control about 74% of the world's total proved crude oil reserves, and in 2017 they produced 43% of total world crude oil. Each OPEC country has at least one NOC, but most also allow international oil companies to operate within their borders.

Oil Imports and Exports

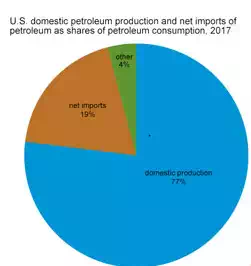

The United States produces a large share of the petroleum it consumes, but it still relies on imports to help meet demand

In 2017, the United States produced1 about 15.4 million barrels of petroleum per day (MMb/d), and it consumed2 about 19.9 MMb/d. Imports from other countries help to supply demand for petroleum.

Petroleum includes more than just crude oil

Petroleum includes more products than just crude oil. Petroleum includes refined petroleum products such as gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, unfinished oils, and other liquids such as fuel ethanol, blending components for gasoline, and other refinery inputs. In 2017, the United States imported about 10.1 MMb/d of petroleum, which included 7.9 MMb/d of crude oil and 2.2 MMb/d of noncrude petroleum liquids and refined petroleum products.

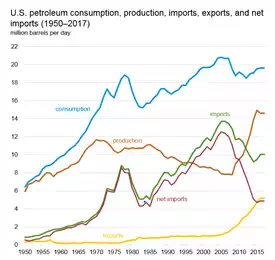

U.S. reliance on petroleum imports has declined in recent years

U.S. petroleum imports peaked in 2005 and generally declined up until 2015. This trend was the result of many factors, including a decline in consumption, increased use of domestic biofuels (ethanol in gasoline and biodiesel in diesel fuel), and increased domestic production of crude oil and hydrocarbon gas liquids. The economic downturn following the financial crisis of 2008, improvements in vehicle fuel economy, and changes in consumer behavior contributed to the decline in U.S. petroleum consumption. Imports and consumption both increased in 2015 through 2017. The net imports (imports minus exports) of petroleum relative to petroleum consumption is one measure of our reliance on imports to help meet petroleum demand. In 2017, net imports of petroleum averaged 3.7 MMb/d, the equivalent of 19% of total U.S. petroleum consumption, which was the lowest percentage since 1967.

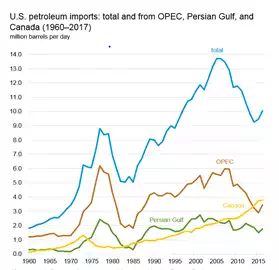

Share of imports from OPEC and Persian Gulf countries has declined, while the share of imports from Canada has increased

U.S. petroleum imports rose sharply in the 1970s, especially from nations that comprise the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). In 1977, when the United States exported relatively small amounts of petroleum, OPEC nations were the source of 70% of total U.S. petroleum imports. Since 1977, the share of total U.S. petroleum imports from OPEC has generally declined. In 2017, OPEC's share of total U.S. petroleum imports was about 33%. OPEC member Saudi Arabia was the largest source of U.S. petroleum imports from OPEC, about 9% of total U.S. petroleum imports. In 2017, about 17% of U.S. petroleum imports came from Persian Gulf countries. Saudi Arabia was the largest source of U.S. imports from Persian Gulf countries. Canada is the largest source of U.S. petroleum imports. Canada's share of U.S. petroleum imports has increased significantly. Canada was the source of 15% of U.S. petroleum imports in 1994 and 40% in 2017. The five largest sources of U.S. petroleum imports by share of total imports in 2017 were

· Canada—40%

· Saudi Arabia—9%

· Mexico—7%

· Venezuela—7%

· Iraq—6%

The United States exports petroleum

Because the United States imports petroleum, it may seem surprising that it also exports petroleum. In 2017, total U.S. petroleum exports averaged about 6.3 MMb/d. Total U.S. petroleum exports included about 1.1 MMb/d of crude oil, about 29% of which went to Canada. Most U.S. petroleum exports are petroleum liquids and refined petroleum products. Because of logistical, regulatory, and quality considerations, exporting some petroleum is the most economical way to meet the market's needs. For example, refiners in the U.S. Gulf Coast region frequently find that it makes economic sense to export some of their gasoline to Mexico rather than shipping it to the East Coast of the United States, because lower cost gasoline imports from Europe may be available to the East Coast.

The five largest destinations of U.S. petroleum exports by share of total exports in 2017 were

· Mexico—17%

· Canada—13%

· China—7%

· Brazil—6%

· Japan—6%

Does the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) know which companies purchase imported crude oil or gasoline?

Although EIA cannot identify which companies sell imported gasoline or gasoline refined from imported oil, it does publish data on the companies that import petroleum into the United States. However, the fact that a given company imported crude oil does not mean that those imports will be used to produce the gasoline sold to motorists as that company's brand of gasoline. Gasoline from different refineries and import terminals is often combined for shipment by pipeline. Different companies owning service stations in the same area may be purchasing gasoline at the same bulk terminal, which may or may not include imported gasoline or gasoline refined from imported oil.

Offshore Oil and Gas:

What is offshore?

Image of a coastline

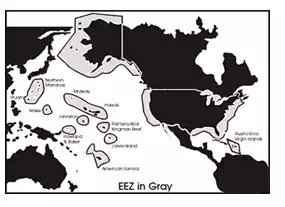

Map showing Exclusive Economic Zone around the United States and Territories

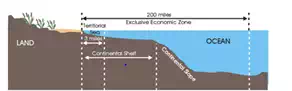

Diagram of shore and ocean overlaid with territorial sea, Exclusive Economic Zone, the Continental Shelf, and Continental Slope

The coastlines of the United States are not the actual borders of the United States. The U.S. border is actually 200 miles away from the coastline. This area around the country is called the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). In 1983, President Ronald Reagan claimed the EEZ in the name of the United States. In 1994, all countries were granted an EEZ of 200 miles from their coastlines under the International Law of the Sea. The ocean floor extends from the coast into the ocean on a continental shelf that gradually descends to a sharp drop, called the continental slope. The width of the U.S. continental shelf varies from 10 miles to 250 miles (16 kilometers to 400 kilometers). The water on the continental shelf is relatively shallow, rarely more than 500 feet to 650 feet (150 meters to 200 meters) deep. The continental shelf drops off at the continental slope, ending in abyssal plains that are 2 miles to 3 miles (3 kilometers to 5 kilometers) below sea level. Many of the plains are flat, while others have jagged mountain ridges, deep canyons, and valleys. The tops of some of these mountain ridges form islands where they extend above the water.

Several federal government agencies manage the natural resources in the EEZ. The U.S. Department of the Interior's Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement manage the development of offshore energy resources by private companies that lease areas for energy development from the federal government. These companies pay royalties to the government on the energy resources they produce from the leased areas in the ocean. Most states control the 3-mile area that extends off of their coasts, but Florida, Texas, and some other states control the waters for as much as 9 miles to 12 miles off of their coasts. Most of the energy the United States gets from the ocean is oil and natural gas from wells drilled on the ocean floor. Other energy sources are under development offshore. America’s first offshore wind energy project, the Block Island Wind Farm off the coast of Rhode Island, became operational in December 2016. Other wind energy projects are under consideration in several other areas off the Atlantic coast. Wave energy, tidal energy, ocean thermal energy conversion, and methane hydrates are other energy sources currently under development or exploration.