Magnetic measurements for an archaeological prospection

The magnetic method started to be used in archaeological prospection with an invention of the proton precession magnetometer which enabled fast and precise measurements with no drift of the instrument. Moreover, further development lead to construction of optically pumped magnetometers, being even more precise and the measurements are fast enough to enable walking-mode measurements. Hence the magnetometry became a standard and most common method in the field of archaeological prospection. Why is the magnetometry so useful in this area and how it can reveal archaeological structures? There are several reasons for this connected to the various types of structures searched for.

The most obvious reason is a search for magnetic iron objects, like remnants of arms or different tools. There are, for example, surveys that found ancient Celtic graves based on magnetic anomalies of swords buried together with fallen warriors. Another easy to find reason could be search for remnants of walls build from magnetic rocks, like basalt. However, much subtle and much more common reason for magnetic anomalies connected with archaeological structures is magnetization of a soil. The soil could be magnetized primarily or secondly.

The primary magnetization comes from disintegration of bedrock and reflects its mineralogy. The magnetite could originate from volcanic bedrock whereas hematite could come from red sandstones. The secondary minerals are results of chemical and biological processes on soil. These processes could produce a maghemite, goethite, hematite and magnetite.

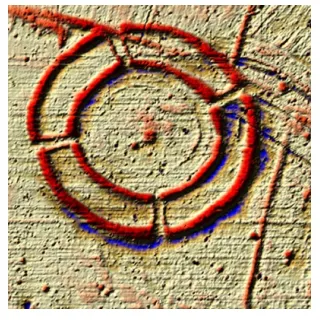

The secondary processes lead to a fact that the topmost soil could be more magnetized than the bedrock. Hence, if there were, e.g. a ditch dug around a castle and the ditch was slowly filled by the topmost soil eroded from the neighbourhood by rains and winds, the filled ditch will have a larger magnetization than the surroundings. Therefore, we can easily map it by its magnetization even if it is not visible on the surface any more (Figs 3.28, 3.29). The same applies on all slowly filled holes, like post holes, dug basements of huts and houses, etc.

The magnetic effect of the soil could be further increased by the thermoremanent magnetization. The fire could increase the temperature of earthen structures above the Curie point and during cooling the atomic dipoles would be aligned into the direction the Earth’s magnetic field and thus increasing its magnetic effect. This is the case of different bulwarks and mounds of ancient settlements being destroyed by fire, e.g. when being captured by enemy armies. The same process also applies to other places affected by fire, like fireplaces, furnaces, etc.