Kicks

A kick is a well control problem in which the pressure found within the drilled rock is higher than the mud hydrostatic pressure acting on the borehole or rock face. When this occurs, the greater formation pressure has a tendency to force formation fluids into the wellbore. This forced fluid flow is called a kick. If the flow is successfully controlled, the kick is considered to have been killed. An uncontrolled kick that increases in severity may result in what is known as a “blowout.”

Factors affecting kick severity

Several factors affect the severity of a kick. One factor, for example, is the “permeability” of rock, which is its ability to allow fluid to move through the rock. Another factor affecting kick severity is “porosity.” Porosity measures the amount of space in the rock containing fluids. A rock with high permeability and high porosity has greater potential for a severe kick than a rock with low permeability and low porosity. For example, sandstone is considered to have greater kick potential than shale, because sandstone has greater permeability and greater porosity than shale.

Yet another factor affecting kick severity is the “pressure differential” involved. Pressure differential is the difference between the formation fluid pressure and the mud hydrostatic pressure. If the formation pressure is much greater than the hydrostatic pressure, a large negative differential pressure exists. If this negative differential pressure is coupled with high permeability and high porosity, a severe kick may occur.

Kick labels

A kick can be labeled in several ways, including one that depends on the type of formation fluid that entered the borehole. Known kick fluids include:

· Gas

· Oil

· Salt water

· Magnesium chloride water

· Hydrogen sulfide (sour) gas

· Carbon dioxide

If gas enters the borehole, the kick is called a "gas kick." Furthermore, if a volume of 20 bbl (3.2 m3) of gas entered the borehole, the kick could be termed a 20-bbl (3.2-m3) gas kick.

Another way of labeling kicks is by identifying the required mud weight increase necessary to control the well and kill a potential blowout. For example, if a kick required a 0.7-lbm/gal (84-kg/m3) mud weight increase to control the well, the kick could be termed a 0.7-lbm/gal (84-kg/m3) kick. It is interesting to note that an average kick requires approximately 0.5 lbm/gal (60 kg/m3), or less, mud weight increase.

Causes of kicks

Kicks occur as a result of formation pressure being greater than mud hydrostatic pressure, which causes fluids to flow from the formation into the wellbore. In almost all drilling operations, the operator attempts to maintain a hydrostatic pressure greater than formation pressure and, thus, prevent kicks; however, on occasion the formation will exceed the mud pressure and a kick will occur. Reasons for this imbalance explain the key causes of kicks:

· Insufficient mud weight.

· Improper hole fill-up during trips.

· Swabbing.

· Cut mud.

· Lost circulation.

Insufficient mud weight

Insufficient mud weight is the predominant cause of kicks. A permeable zone is drilled while using a mud weight that exerts less pressure than the formation pressure within the zone. Because the formation pressure exceeds the wellbore pressure, fluids begin to flow from the formation into the wellbore and the kick occurs.

These abnormal formation pressures are often associated with causes for kicks. Abnormal formation pressures are greater pressures than in normal conditions. In well control situations, formation pressures greater than normal are the biggest concern. Because a normal formation pressure is equal to a full column of native water, abnormally pressured formations exert more pressure than a full water column. If abnormally pressured formations are encountered while drilling with mud weights insufficient to control the zone, a potential kick situation has developed. Whether or not the kick occurs depends on the permeability and porosity of the rock. A number of abnormal pressure indicators can be used to estimate formation pressures so that kicks caused by insufficient mud weight are prevented (some are listed in Table 1).

Table 1- Abnormal Pressure Indicators

An obvious solution to kicks caused by insufficient mud weights seems to be drilling with high mud weights; however, this is not always a viable solution. First, high mud weights may exceed the fracture mud weight of the formation and induce lost circulation. Second, mud weights in excess of the formation pressure may significantly reduce the penetration rates. Also, pipe sticking becomes a serious consideration when excessive mud weights are used. The best solution is to maintain a mud weight slightly greater than formation pressure until the mud weight begins to approach the fracture mud weight and, thus, requires an additional string of casing.

Improper hole fill-up during trips

Improperly filling up of the hole during trips is another prominent cause of kicks. As the drillpipe is pulled out of the hole, the mud level falls because the pipe steel no longer displaces the mud. As the overall mud level decreases, the hole must be periodically filled up with mud to avoid reducing the hydrostatic pressure and, thereby, allowing a kick to occur.

Several methods can be used to fill up the hole, but each must be able to accurately measure the amount of mud required. It is not acceptable—under any condition—to allow a centrifugal pump to continuously fill up the hole from the suction pit because accurate mud-volume measurement with this sort of pump is impossible. The two acceptable methods most commonly used to maintain hole fill-up are the trip-tank method and the pump-stroke measurements method.

The trip-tank method has a calibration device that monitors the volume of mud entering the hole. The tank can be placed above the preventer to allow gravity to force mud into the annulus, or a centrifugal pump may pump mud into the annulus with the overflow returning to the trip tank. The advantages of the trip-tank method include that the hole remains full at all times, and an accurate measurement of the mud entering the hole is possible.

The other method of keeping a full hole—the pump-stroke measurement method—is to periodically fill up the hole with a positive-displacement pump. A flowline device can be installed with the positive-displacement pump to measure the pump strokes required to fill the hole. This device will automatically shut off the pump when the hole is full.

Swabbing

Pulling the drillstring from the borehole creates swab pressures. Swab pressures are negative, and reduce the effective hydrostatic pressure throughout the hole and below the bit. If this pressure reduction lowers the effective hydrostatic pressure below the formation pressure, a potential kick has developed. Variables controlling swab pressures are:

· Pipe pulling speed

· Mud properties

· Hole configuration

· The effect of “balled” equipment

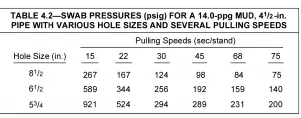

Some swab pressures can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2- Swab Pressures (psig) for a 14-ppg mud 4½ -in. Pipe With Various Hole Sizes and Several Pulling Speeds

Cut mud

Gas-contaminated mud will occasionally cause a kick, although this is rare. The mud density reduction is usually caused by fluids from the core volume being cut and released into the mud system. As the gas is circulated to the surface, it expands and may reduce the overall hydrostatic pressure sufficient enough to allow a kick to occur.

Although the mud weight is cut severely at the surface, the hydrostatic pressure is not reduced significantly because most gas expansion occurs near the surface and not at the hole bottom.

Lost circulation

Occasionally, kicks are caused by lost circulation. A decreased hydrostatic pressure occurs from a shorter mud column. When a kick occurs from lost circulation, the problem may become severe. A large volume of kick fluid may enter the hole before the rising mud level is observed at the surface. It is recommended that the hole be filled with some type of fluid to monitor fluid levels if lost circulation occurs.