Coking

Despite the development of catalytic cracking processes, coking processes have survived as a popular refining process all over the world to refine the heavy end of crudes or heavy oils through carbon rejection as coke. Coking is the most severe thermal process used in the refinery to treat the very bottom-of-the-barrel of crude oil, i.e., vacuum residue.

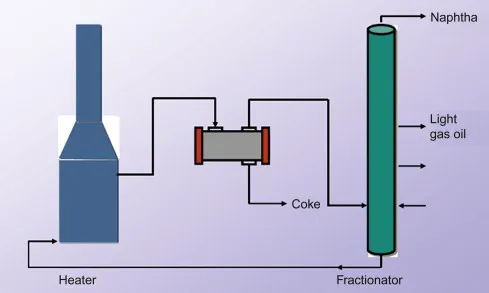

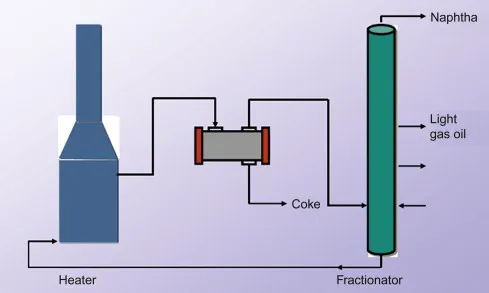

Because of the high severity of thermal cracking during coking, the residue feed is completely converted to gas, light and medium distillates, and coke with no production of residual oil. Three different coking processes are used in the refineries: delayed coking, fluid coking, and flexi-coking (a variation of fluid coking). The common objective of the three coking processes is to maximize the yield of distillate products in a refinery by rejecting large quantities of carbon in the residue as solid coke, known as petroleum coke. Complete rejection of metals with the coke product provides an attractive alternative for upgrading the extra-heavy crude and bitumen, and that is particularly useful for initial processing of tar (or oil) sands for liberating the hydrocarbons from the sand that is left behind with the coke. Finding markets for the coke product as fuel or as filler for manufacturing anodes for the electrolysis of alumina (possible only with petroleum coke from delayed coking) makes the economics of coking more attractive by creating value for the rejected carbon. Sulfur and metal contents of the petroleum coke, as determined by the sulfur and metal contents of the residue feed, are two important factors that affect the commercial value of petroleum coke. Of the two coking processes, delayed coking is the preferred approach in many refineries that process heavy crudes.