Network Plan

Networking computers first and tracking the connections later can quickly become confusing and unmanageable as you try to find which computer communicates with and shares resources with which other computers. In your human network, do you share everything with your friends? In your family network, would you want your parents or guardians to know your every thought? You have your information-sharing plan in your head, and it is important to keep track of it so you don’t make a mistake and share something where it was not intended.

Similar concerns must be considered while designing a computer network. Before you even connect your first computers together, you should have a plan. A network plan, therefore, is a formally created product that shows all the network’s components and the planned connections between them. Such a plan is also used to manage the various types of information. Your plan should show what types of information are stored where, and who is allowed to use each type.

Information Management

Your network plan should help you manage the information gathered, stored, and shared between your users. If you were given an empty three-drawer filing cabinet and told to use it to organize your company’s information, you would have an excellent (although manual) example of a filing system that needs a plan. Having an overall guide that tells you who will be allowed access to the three drawers will help determine what you store in each one. Once you have that part of the plan, you could put the least-used information in the bottom drawer, the more-used in the middle drawer, and the most-used in the top drawer so that it is easier for your users to access their information. Knowing who needs to know what, and its corollary— who does not need to know what—lets you determine whether to lock a particular drawer, too.

Even when we discuss implementing a three-drawer manual filing system, the importance of having a network plan ahead of time becomes evident. If you put the limited-access material in a drawer open to all employees, how do you keep it secure? Additional security measures (like adding a lock to a drawer, or moving the secure information somewhere else) may be required later. A networking plan could tell you that as specific types of sensitive data (like medical, personal, or payroll information) are gathered or grouped, they should be stored higher in the hierarchical structure (ranked from most sensitive to least sensitive), and this can save you time in the end. That plan should specify that the access requirements are stricter for sensitive data and reduce the number of people able to use specific types of information.

The distribution side of the networking plan, as opposed to the accumulation side of the plan discussed above, should spell out that the more an individual has access to the data in storage, the less they should be able to share groups of information entrusted to them. For example, you may not mind sharing your first name, but you would probably object to an instructor openly distributing all information in your school records to anyone requesting it.

Information’s Importance

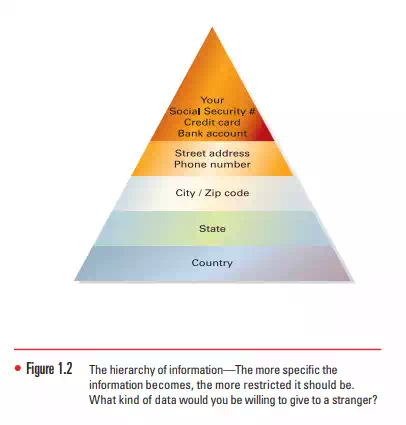

If you think about the manual filing system we discussed using a filing cabinet, an important computing concept is easy to recognize. Some information is more important or more sensitive than the rest. It is usually obvious in real filing cabinet systems, because the top drawer is usually where the most sensitive information is stored, and it is locked. Few people in an organization have access to that information. For example, credit card or Social Security numbers are information that should be given the highest level of security—access to that information is given only to a limited number of people in a company. On the other hand, some information, such as Web pages, newsletters, and product information, is created for everyone to see, even outside a company. Figure 1.2 shows how this kind of information is organized into a hierarchy of information, where the most detailed information is found at the top and the more general, less secure information is located at the bottom. How much information would you be willing to provide about yourself to a perfect stranger? Country of birth? Sure. State of residence? Why not? But you might have second thoughts about advertising your street address or phone number to a stranger.

The collection and proper manipulation of many seemingly unimportant pieces of information, and the effective tracking of them, makes information management on networks so important, just as when you are maintaining a manual filing system. A single piece of information in a data field, such as your first name, can seem unimportant. However, by combining your first name with other pieces of related information, like your last name, address, age, gender, and phone number (stored in other data fields), the pieces can be put together to create a data record, which can accurately describe something (or someone) that is important—like you. Finally, combining similar records (such as records describing all your classmates) creates a file that, because it contains sensitive information from more than one source, is more sensitive than a single record. Information sharing, therefore, has serious security issues to be considered, and network access to data must be evaluated carefully so that only those who need it can access it.