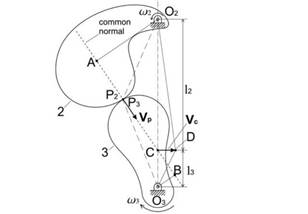

The transformation of motion from one shaft to another shaft requires three bodies: a frame (the position of each shaft is fixed in the frame) and two gears. Consider a general case when two disks with arbitrary profiles shown in figure 1, represent gears 2 and 3. Also assume that disk 2 rotates with the constant angular velocity ω2. The motion is transferred through the direct contact at point P (note that P2 and P3 are the same point P, but the first point is associated with disk 2 whereas the second point is associated with disk 3). We need to find out whether or not the angular velocity ω3 will remain constant and if not, what is required to make it remain constant. The answer is given byKennedy’s theorem.

Kennedy’s theorem identifies the fundamental property of three rigid bodies in motion.

The three instantaneous centers shared by three rigid bodies in relative motion to one another all lie on the same straight line.

First, recall about that the instantaneous center of velocity, it is defined as the instantaneous location of a pair of coincident points of two different rigid bodies for which the absolute velocities of two points are equal. If one considers body 2 and the frame (represented by point O2) in figure 1, then the instantaneous center of these two bodies is point O2, which belongs to the frame and to disk 2. The absolute velocities of both bodies at point O2 are zero.

Figure 1: Kennedy’s theorem illustration

The same is valid for disk 3 and the frame represented by point O3. For the three bodies in motion there are three instantaneous centers: for all combinations of pairs. Thus, there is an instantaneous center between the two disks.

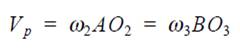

Since point P is a common point for two disks in figure 1, for each disk the velocity component at this point directed along the common normal is the same and equal to Vp. One can move this velocity vector along the common normal until it intersects the line connecting the two instantaneous centers O2 and O3 at point C. According to Kennedy’s theorem, this point (P) is the instantaneous center of velocity for the two disks. Indeed, the velocity Vp, the only instantaneous common velocity for the two disks (disk 2, disk 3) will be equal to

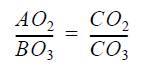

Triangles AO2C and BO3C are similar, it follows that

From the above relationship, the ratio of angular velocities is equal to

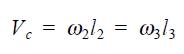

Where lengths l2 and l3 denote O2C and O3C, respectively (see the above figure 1).

Velocity Vc in figure 1 is a common velocity for the two disks since

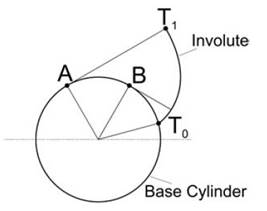

Figure 2: Illustration of the involute profile generation

Velocity Vc is also the absolute velocity of each body at this point because there cannot be another velocity component along the line O2O3 (since the distance between the frame points O2 and O3 is not changing and bodies 2 and 3 are assumed to be rigid).

Note that the relative velocity of two disks at point C is zero, whereas relative velocity at point P is not zero.

The above equation 3 gives the transformation of angular velocities from disk 2 to disk 3. It can be seen from the above relation, in order to remain kinematic ratio (ω2/ω3) constant, legthss l2 and l3 must not change. It is clear from figure 1, however, that for arbitrary profile shapes the common normal changes its direction during the motion, and thus point C moves along line O2O3. Thus, the problem of meeting the constant ratio requirement is to find such disk profiles that the kinematic ratio remains constant. It will be shown in the following that if the disk profile is described by theinvolute function, the common normal does not change its direction.