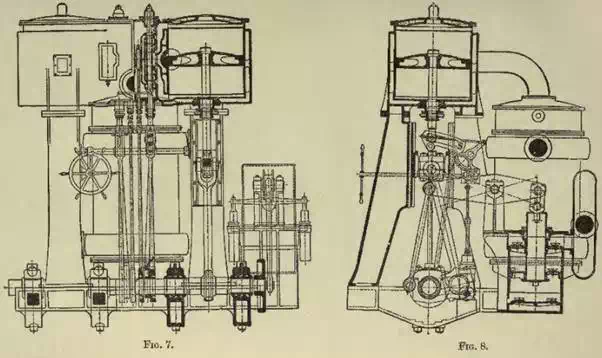

Vertical (compound) engines.

The vertical type of engine, with cylinders at the top and crank-shaft below,

was adopted for merchant ships long before it was introduced into the Royal

Navy, because it was a necessity in most warships that all the machinery should

be kept below the water-line, and horizontal engines alone satisfied this

condition. Figs. 7 and 8 show a vertical engine of the type fitted in the

mercantile marine.

Vertical engines possess many practical

advantages over horizontal engines, especially in connection with the

working of the cylinders and pistons, and general accessibility of the engine.

When, therefore, the twin-screw system was adopted for armour-clad ships,

vertical compound engines were fitted, with a middle line water-tight bulkhead

separating the two sets. By dividing the power into two parts, each set

of engines, even in a ship of great power, would be of moderate dimensions, and

although the whole of the machinery might not in all cases be entirely below

the water-line, the parts above would be protected, not only by armour plating,

but by a body of coal in addition, the coal-bunkers being continued on each

side of the engine room.

This extension of the use of vertical engines has continued and been applied to

all classes of vessel, and special means for protecting the cylinders have

often been fitted. At the present time new engines for the Navy are being made

vertical for all classes of vessel.

Three-cylinder compound engines

As the power of compound engines increased, the dimensions of the low-pressure

cylinders became so great that it was found desirable to fit two low-pressure

cylinders instead of one, in consequence of the difficulties experienced in

obtaining sound castings of large size, and to keep the size of the

reciprocating parts as small as possible. This led to what is known as the

three-cylinder compound engine, which is simply a modification of the ordinary

two-cylinder compound engine. Figs. 9 and 10 show a vertical compound engine of

the three-cylinder type.