History And Progress.

THE earliest steam engines were simply

reciprocating engines, and for many purposes such engines are still used even

at the present day. Until, however, a suitable method of turning reciprocating into

rotative motion had been discovered and utilised not any progress was made in

adapting the steam-engine to the propulsion of vessels. The adoption of the

crank effected this desirable object, enabled the power of the engine to

be transmitted to the propeller smoothly and without shock, and was an

indispensable step in the progress of steam navigation.

The marine steam-engine may justly be considered as a production of the present

century. In the latter part of the eighteenth century several attempts were

made to adapt the steam-engine for the propulsion of boats, but none of them

were quite successful.

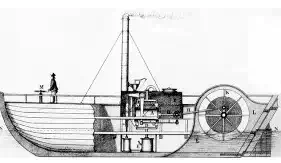

The first practical steamboat was built on the Clyde, in 1801, by William

Symington, for Lord Dundas. She was called the "Charlotte Dundas,"

and was worked for some time with success as a tug on the Forth and Clyde

Canal, but was withdrawn from this service in consequence of an

apprehension that the banks of the canal would suffer from the wash of the

propeller. This boat was fitted with a single paddle-wheel placed near the

stern, driven by a horizontal direct-acting engine, with connecting-rod and

crank, and the general arrangement of her machinery would be considered

creditable even at the present day.

|

|

|

|

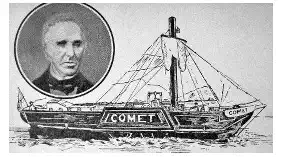

he first recorded instance of steam navigation proving commercially successful was in America, where, in 1807, Robert Fulton built a steam vessel called the 'Clermont,' propelled by paddles driven by a Boulton & Watt engine. In 1812 Henry Bell built a vessel called the 'Comet,' which was successfully worked on the Clyde as a passenger steamer between Glasgow and Greenock. The 'Comet' was propelled by two pairs of paddles, each paddle having four floats or blades, somewhat resembling a pair of canoe paddles, crossed at right angles. The paddles were driven by an engine of somewhat peculiar design, which, however, approximated to the side-lever engine of a later day. This small boat was the first passenger steamer in Europe.

From this date the success of steam navigation may be said to have been

secured, and the advancement that has been made since has not consisted so much

in the discovery of new principles as in the extension of old ones, and the

introduction and development of improved mechanism and workmanship, with

consequent economy of fuel. The result has been a progressive increase in the

size, power, and speed of steamships and in the extent of their voyages;

so that at the present day we have ships displacing 19,500 tons, and capable of

being driven at a speed of 22 knots by engines developing more than 30,000

indicated horse-power, while even larger vessels are under construction.