Optimal Operations of Generators on a Bus Bar

Optimal Operations of Generators on a Bus Bar – The major component of generator operating cost is the fuel input/hour, while maintenance contributes only to a small extent. The fuel cost is meaningful in case of thermal and nuclear stations, but for hydro stations where the energy storage is ‘apparently free’, the operating cost as such is not meaningful. A suitable meaning will be attached to the cost of hydro stored energy in Section 7.7 of this chapter. Presently we shall concentrate on fuel fired stations.

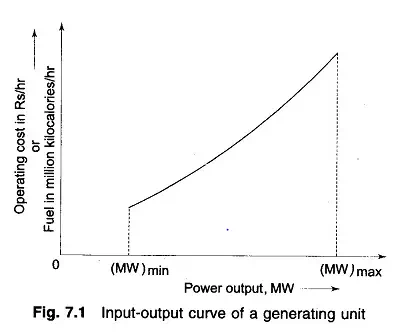

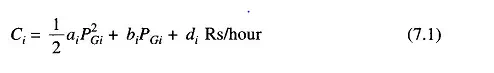

The input-output curve of a unit* can be expressed in a million kilocalories per hour or directly in terms of rupees per hour versus output in megawatts. The cost curve can be determined experimentally. A typical curve is shown in Fig. 7.1 where (MW)min is the minimum loading limit below which it is uneconomical (or may be technically infeasible) to operate the unit and (MW)max is the maximum output limit The input-output curve has discontinuities at steam valve openings which have not been indicated in the figure. By fitting a suitable degree polynomial, an analytical expression for operating cost can be written as where the suffix i stands for the unit number. It generally suffices to fit a second degree polynomial, i.e.

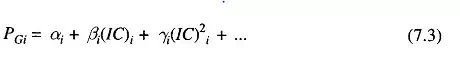

The slope of the cost curve, i.e. dCi/dPGi is called the incremental fuel cost (IC), and is expressed in units of rupees per megawatt hour (Rs/MWh). A typical plot of incremental fuel cost versus power output is shown in Fig. 7.2. If the cost curve is approximated as a quadratic as in Eq. (7.1), we have

i.e. a linear relationship. For better accuracy incremental fuel cost may be expressed by a number of short line segments (piecewise linearization). Alternatively, we can fit a polynomial of suitable degree to represent IC curve in the inverse form

Optimal Operation

Let us assume that it is known a priori which generators are to run to meet a particular load demand on the station. Obviously

![]()

where PGi, max is the rated real power capacity of the ith generator and PD is the total power demand on the station. Further, the load on each generator is to be constrained within lower and upper limits, i.e.

![]()

Considerations of spinning reserve, to be explained later in this section, require that

by a proper margin, i.e. Eq. (7.6) must be a strict inequality.

Since the operating cost is insensitive to reactive loading of a generator, the manner in which the reactive load of the station is shared among various online generators does not affect the operating economy*. The question that has now to be answered is: ‘What is the optimal manner in which the load demand PD must be shared by the generators on the bus?’ This is answered by minimizing the operating cost

under the equality constraint of meeting the load demand, i.e.

where k = the number of generators on the bus.

Further, the loading of each generator is constrained by the inequality constraint of Eq. (7.5).

Since Ci(PGi) is non-linear and Ci is independent of PGj(j≠i), this is a separable non-linear programming problem.

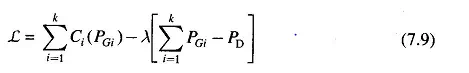

If it is assumed at present, that the inequality constraint of Eq. (7.4) is not effective, the problem can be solved by the method of Lagrange multipliers. Define the Lagrangian as

where λ is the Lagrange multiplier.

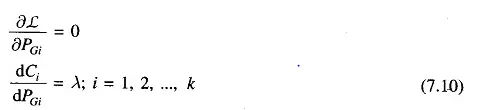

Minimization is achieved by the condition

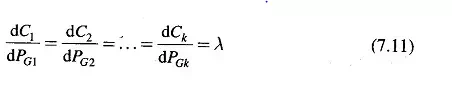

where dCi/dPGi is the incremental cost of the ith generator (units: Rs/MWh), a function of generator loading PGi. Equation (7.10) can be written as

i.e. the optimal loading of generators corresponds to the equal incremental cost point of all the generators. Equation (7.11), called the coordination equations numbering k are solved simultaneously with the load demand equation (7.8) to yield a solution for the Lagrange multiplier λ and the optimal loading of k generators. This is illustrated by means of Example 7.1 at the end of this section.

Computer solution for optimal loading of generators can be obtained iteratively as follows:

1. Choose a trial value of λ, i.e. IC = (IC)°.

2. Solve for PGi (i=1, 2, …, k) from Eq. (7.3).

3. If |ΣiPGi-PD|< ε (a specified value), the optimal solution is reached. Otherwise,

4. Increment (IC) by Δ(IC), if [ΣPGi-PD]<0 or decrement (IC) by Δ(IC)

if [ΣPGi-PD]>0 and repeat from step 2. This step is possible because PGi is monotonically increasing function of (IC).

Consider now the effect of the inequality constraint (7.5). As (IC) is increased or decreased in the iterative process, if a particular generator loading PGj reaches the limit PGj,max or PGj, min, its loading from now on is held fixed at this value and the balance load is then shared between the remaining generators on equal incremental cost basis. The fact that this operation is optimal can be shown by the Kuhn-Tucker theory.