Diaphragm Construction

The operating mechanism of a diaphragm valve is not exposed to the media within the pipeline. Sticky or viscous fluids cannot get into the bonnet to interfere with the operating mechanism. Many fluids that would clog, corrode, or gum up the working parts of most other types of valves will pass through a diaphragm valve without causing problems. Conversely, lubricants used for the operating mechanism cannot be allowed to contaminate the fluid being handled. There are no packing glands to maintain and no possibility of stem leakage. There is a wide choice of available diaphragm materials. Diaphragm life depends upon the nature of the material handled, temperature, pressure, and frequency of operation.

Some elastomeric diaphragm materials may be unique in their excellent resistance to certain chemicals at high temperatures. However, the mechanical properties of any elastomeric material will be lowered at the higher temperature with possible destruction of the diaphragm at high pressure. Consequently, the manufacturer should be consulted when they are used in elevated temperature applications.

All elastomeric materials operate best below 150°F. Some will function at higher temperatures. Viton, for example, is noted for its excellent chemical resistance and stability at high temperatures. However, when fabricated into a diaphragm, Viton is subject to lowered tensile strength just as any other elastomeric material would be at elevated temperatures. Fabric bonding strength is also lowered at elevated temperatures, and in the case of Viton, temperatures may be reached where the bond strength could become critical.

Fluid concentrations is also a consideration for diaphragm selection. Many of the diaphragm materials exhibit satisfactory corrosion resistance to certain corrodents up to a specific concentration and/or temperature. The elastomer may also have a maximum temperature limitation based on mechanical properties which could be in excess of the allowable operating temperature depending upon its corrosion resistance. This should be checked from a corrosion table.

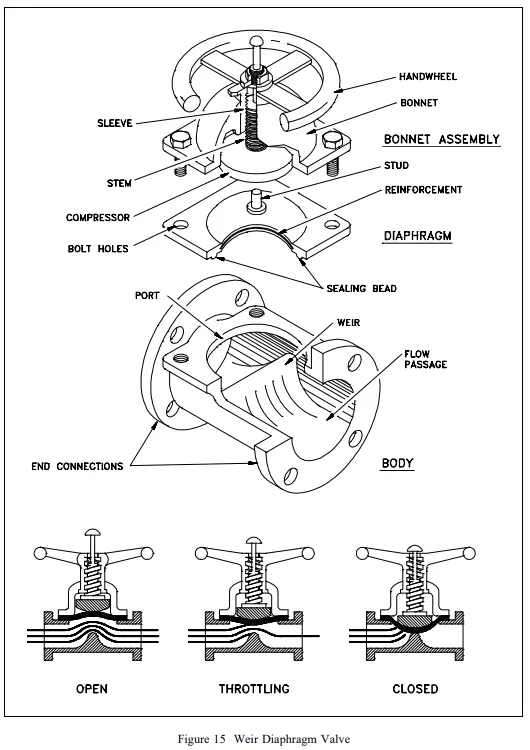

Diaphragm Valve Stem Assemblies

Diaphragm valves have stems that do not rotate. The valves are available with indicating and non-indicating stems. The indicating stem valve is identical to the non-indicating stem valve except that a longer stem is provided to extend up through the handwheel. For the nonindicating stem design, the handwheel rotates a stem bushing that engages the stem threads and moves the stem up and down. As the stem moves, so does the compressor that is pinned to the stem. The diaphragm, in turn, is secured to the compressor.

Diaphragm Valve Bonnet Assemblies

Some diaphragm valves use a quick-opening bonnet and lever operator. This bonnet is interchangeable with the standard bonnet on conventional weir-type bodies. A 90° turn of the lever moves the diaphragm from full open to full closed. Diaphragm valves may also be equipped with chain wheel operators, extended stems, bevel gear operators, air operators, and hydraulic operators.

Many diaphragm valves are used in vacuum service. Standard bonnet construction can be employed in vacuum service through 4 inches in size. On valves 4 inches and larger, a sealed, evacuated, bonnet should be employed. This is recommended to guard against premature diaphragm failure.

Sealed bonnets are supplied with a seal bushing on the non-indicating types and a seal bushing plus O-ring on the indicating types. Construction of the bonnet assembly of a diaphragm valve is illustrated in Figure 15. This design is recommended for valves that are handling dangerous liquids and gases. In the event of a diaphragm failure, the hazardous materials will not be released to the atmosphere. If the materials being handled are extremely hazardous, it is recommended that a means be provided to permit a safe disposal of the corrodents from the bonnet.