US Supreme Court split on the partisan politics of district drawing

At the end of June, the U.S.

Supreme Court waded into the fight over political partisanship in American

politics. In a 5-4 decision, the Court held in Rucho v. Common Cause that federal courts cannot strike down district maps because

they are designed to help or hurt a particular political party. Notably, the

Court itself was split along partisan lines, with Chief Justice Roberts penning

the majority opinion, joined by the other four conservatives; and, Justice

Kagan writing a blistering dissent, concurred in by the other three liberals.

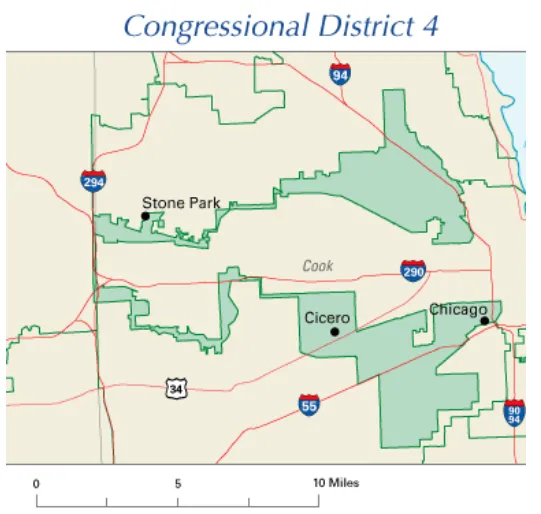

The case concerned two extreme examples of gerrymandering – one to favor the Republicans in North Carolina and the other to favor the Democrats in Maryland. In both cases, state leaders had relied on new technology and electoral experts to openly construct districts to enhance their own party’s power. The plaintiffs alleged that this gerrymandering violated their First Amendment right to free speech, the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Article I §2 of the Constitution. The lower courts in both cases had ruled in favor of the plaintiffs.

The majority held that partisan gerrymandering presented a nonjusticiable political question. “What the appellees and dissent seek is an unprecedented expansion of judicial power,” Roberts wrote. “That intervention would be unlimited in scope and duration – it would recur over and over again around the country with each new round of districting, for state as well as federal representatives.” Not all partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional and the problem, according to the majority, is that there is no “clear, manageable and politically neutral test” for the courts to apply to determine when it has gone too far. Furthermore, Roberts argued that the Constitution’s framers were well aware of the practice of partisan gerrymandering and never suggested that the courts should intervene. Therefore, the majority concluded, the matter is best left to the states to regulate.

In dissent, Kagan accused the majority of an unprecedented abdication of their responsibility to remedy a constitutional violation, emphasizing the significance of the issue to American democracy. “The partisan gerrymanders in these cases deprived citizens of the most fundamental of their constitutional rights,” wrote Kagan. “In doing so, the partisan gerrymanders here debased and dishonored our democracy.” Kagan rebutted the majority’s reasoning on two key points. First, although America’s history of gerrymandering dates back to the founding, the modern practice is significantly different. New technology now allows for a level of precision and accuracy that makes gerrymandering a far greater threat to democracy than ever before, as evidenced in the cases of North Carolina and Maryland. Second, the lower courts have been converging on a standard for adjudicating these cases rooted in the laws of the states themselves, which disproves the majority’s assertion that there is no justiciable standard for courts to apply.

While the Supreme Court has never struck down a partisan gerrymander in previous cases brought before it, the Court has found racial gerrymandering to violate the Constitution and has struck down maps for deviating too far from the “one person, one vote” principal. As federal courts have struggled in recent years with the question of whether judicial intervention in the drawing of district maps can be extended to cases of partisan gerrymandering, Justice Kennedy had repeatedly left the door open to federal courts holding some districting plans unconstitutional. With Justice Kavanaugh now in Kennedy’s seat, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority has been able to make significant strides in advancing its legal agenda in this and other cases. Increasingly, the Court has become a flashpoint in partisan politics with many of the Democratic presidential candidates advocating packing the court – an idea that has been dormant since FDR’s attempt nearly a century ago. If Justice Kagan is right that the legislative branches at both the state and federal levels will be unable to remedy extreme gerrymandering, the partisan politics unleashed by the Rucho decision could ultimately infect the judiciary itself.