Magna Carta: The Origin of Modern Human Rights

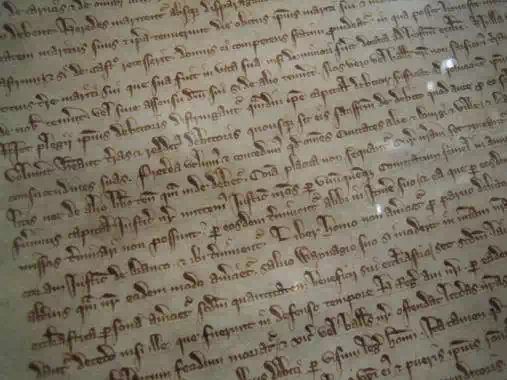

Magna Carta was accepted by King John of England in 1215 and granted certain rights to English noblemen.

Although the rights it gave, and the number of people to whom it gave them, were few, Magna Carta became a symbol for subjecting powerful rulers to law and fundamental rights. It holds an historic legacy as “the Great Charter of the Liberties” and its influence still endures today.

Magna Carta has been described as a “major constitutional document” and “the banner, the symbol, of our liberties”. But, most of the provisions of the original Magna Carta concerned the property of English nobles, who forced King John to seal (agree to) the document at Runnymede in 1215.

Most of the original provisions are no longer in force, because they are not really relevant to today’s world. One interesting provision, although not still law, is responsible for the beloved pint, as it provided for ale to be served in a standard measure, called the ‘London quarter’ (2 pints).

The Words of Magna Carta – “Pure Gold”

Certain provisions of the Magna Carta which remain valid contain some of the most important rules in the history of English law. Sir Edward Coke, a 17th century English lawyer and politician, described these provisions as “pure gold”. Lord Bingham, a judge of the UK’s highest court, proclaimed that the words still “have the power to make the blood race”.

Clause 39 of the Magna Carta states:

No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.

Magna Carta’s Clause 40 states:

To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.

(Slightly amended, these two clauses make up Article 29 of a consolidated version of Magna Carta, which was issued in 1225.)

Together, these provisions form the origins of what became the right to freedom from arbitrary detention and the right to a fair trial. Although originally intended only for a small class of people (the English nobility), these important provisions paved the way for our modern human rights laws, under which the State must respect and protect the rights and liberties of people within their jurisdiction.

Magna Carta and Human Rights Today

Magna Carta recognised three great constitutional ideas, which we still see today. First, fundamental rights can only be taken away or interfered with by due process and in accordance with the law. Second, government rests upon the consent of the governed, which is reinforced by our right to free and fair elections. Third, government, as well as the governed, is bound by the law, so the Human Rights Act 1998 makes it clear that public authorities can’t infringe our rights.

Advances in basic rights protection are rarely achieved without criticism or attempts to undermine them. After Magna Carta was sealed, Pope Innocent III declared it “illegal, unjust, harmful to royal rights and shameful to the English people”. Still, Magna Carta remains important today. The UK’s highest court in January 2017 declared that it contained the ‘most long-standing and fundamental’ rights.

In the intervening 800 odd years, the ideas behind Magna Carta have been exported throughout the world. The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was hailed by Eleanor Roosevelt, chair of the drafting committee, as “the international Magna Carta of all men everywhere”.

The rights contained in the UDHR had great influence on the Human Rights Convention, which takes effect in UK law through the Human Rights Act 1998. The links between these laws and the values which underlie Magna Carta are clear; modern human rights laws show our commitment to the ancient ideas that power must be subjected to the rule of law and must not be allowed to violate fundamental freedoms.