The 3 business models that matters for connected hardware start-ups

Hardware has changed.

It used to be that a “hardware business” sold widgets made in China at a 30% gross margin. These widgets were protected with patents, manufactured by the millions, and replaced by new and better widgets 18 months later. Inevitably, a bigger company with deeper pockets, stronger manufacturing relationships, and better execution would come along with a slightly better widget at a lower price and make more money. First-movers often wound up losing market share and margins due to aggressive competition. They’d end up with a commoditized product line and a company headed for low margins and even failure. Let’s take a look at Jawbone.

Jawbone has been around for awhile (16 years). They’ve brought to market two major products that have become wildly popular categories worth billions of dollars (bluetooth headsets and portable bluetooth speakers). They’ve attracted top talent (like Yves Behar and Sameer Samat). They’ve raised money from some of the best investors in the world (Sequoia Capital, Andreessen-Horowitz, Kleiner Perkins, and Khosla Ventures). If you pattern-match to successful companies in the startup ecosystem, they look like a pretty sure bet.

So why are they struggling while younger “hardware” companies are IPO’ing with record-setting results?

A plethora of bluetooth speakers that have entered the market after the Jambox. Image complied from various sources

ommoditization. They have a dis-harmonious product line with good distribution but a weak-to-moderate brand. Few consumers recognize Jawbone as the “World’s Greatest X” because speakers, headsets, and fitness trackers don’t tell a cohesive story like Beats does around music or Fitbit does around fitness. Jawbone feels like a distribution company desperately trying to find the Next Big Thing.

What makes today’s hardware successes like GoPro, Arista, Fitbit, Nest, Dropcam, Zayo, and Oculus different?

The modern hardware business is a trojan horse for software.

Every company listed above is really a software company masquerading as a hardware company. The majority of their focus is on the digital aspects of their product and business. Hardware is the enabler. Many have recurring revenue and nearly all have more software engineers than hardware engineers.

As software works into the product equation, companies become less susceptible to commoditization. Software services are harder to copy. They can increase switching cost and provide more opportunities to interact with consumers and build brand. We group new hardware business models in three distinct categories:

1. Hardware-as-a-Service

The most commonly cited business model for connected hardware startups relies on the sale or lease of a device that only works when a recurring fee is paid. Almost always this fee is a software license or service fee, sometimes paid on a time basis (annual, monthly) and sometimes on a metering basis (per byte or user). Hardware as a service companies optimize for high lifetime value through recurring fees rather than a hefty gross margin on the initial sale.

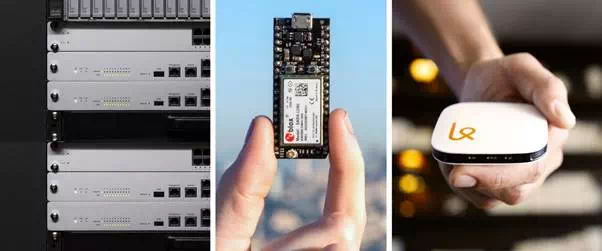

Some companies that are built around hardware-as-a-service:

· Meraki (acquired by Cisco) sells beautiful IT infrastructure coupled with a web-based management platform. Think of their product as your IT guy in a box. While customers put down a good bit of cash for the hardware the vast majority of the LTV (lifetime value) is paid in annual software contracts.

· Particle helps hardware companies integrate WiFi and 3G into their products. Customers can buy affordable development kits to help them get off the ground and then easily transition to full-scale-production versions that use the same code. Particle’s business model leverages recurring software/data licenses just like an MVNO (mobile virtual network operator).

· Karma enables internet connectivity for any device anywhere. End-users only pay for the data their devices consume and are even allowed to share data with other people around them. Karma’s business model optimizes for consumption of data and charges users a slight premium versus the 4G data charges they incur.

· DipJar is a tip jar and donation box for credit cards. Each store owner or charity pays a fixed monthly fee per jar. In addition, DipJar charges a small transaction fee with each tip or donation. Their business model optimizes for tipping and donations rather than making money on the sale/lease of the jars themselves.

2. Hardware-enabled Services

Hardware-enabled service products are almost identical to hardware-as-a-service products but the service is optional. While this may sound like a small tweak, it fundamentally changes the economics of the business. Every hardware product that uses this business model must make a significant margin on the sale of each unit. To date, this model is largely found in consumer products where freemium behavior is already common.

Some companies that are built around hardware-enabled service:

· Dropcam (acquired by Nest) sells a dead-simple security camera system and has a nice margin at $199 MSRP. However Dropcam charges for cloud video storage starting at $10/month.

· Canary sells a modern security system that learns about your home and provides you with alerts straight to your phone. The $249 product isn’t light on the wallet but it’s a far better experience than systems sold by ADT or Honeywell. Canary also has a range of service plans to record, store, and bookmark captured footage that are as expensive as $30/month.

· Meural builds a beautiful digital art frame. The $499 price point is designed to support a growing business but they also monetize the incredibly high-resolution art users can display on their frame.

· Fitbit is well-known for its fitness products. Don’t be fooled by the low price, Fitbit makes a healthy margin on every product, even at $79. But there are also millions of active users on Fitbit’s premium software platform that are paying $50/year for additional features.

3. Consumables

An increasing number of startups are starting to experiment with a business model popularized by Keurig/Green Mountain. It’s one of the most challenging models for hardware companies, but one that’s extremely defensible. This model relies on a one-time hardware sale of the “dispenser” and continual sales of the “consumable” that users are excited to purchase but require the dispenser to consume. Not only does this model usually require a web/mobile software product (hard) and a hardware product (harder), it demands a super efficient and fast custom distribution system built from scratch (hardest).

· Petnet sells a WiFi-connected automatic pet feeder that can ship pet food straight to your door exactly when you need it. The incredibly low price of the feeder ($99) is offset by the direct-to-your-door food service which the vast majority of users sign up for once their food runs out. Petnet acts as the retailer of the food, making a margin on each sale.

· Kuvée is disrupting the wine buying and drinking experience. Like Keurig or Nespresso, each Kuvée user owns a Smart Bottle “dispenser” device which can pour single servings from the company’s 750ml wine cartridges. Cartridges can be ordered directly from the bottle and are shipped to the user’s door next day. Nearly all of Kuvée’s profit will come from the sale of wine.

· Amazon Kindle This permutation of the Keurig model relies on digital content (books) rather than consumables, but in practice it’s nearly identical. Amazon loses money on every Kindle sale and instead monetizes digital book content.

· Rest Devices sells a connected baby monitor platform enabled by custom-made onesies. Parents can choose additional onesies as their little one gets bigger and/or if they prefer to accessorize with different styles. While Rest makes money on both the initial sale and the onesies, the company expects to see a larger portion of their LTV come from the clothing.