Training and Entrepreneurship Skills for Growth

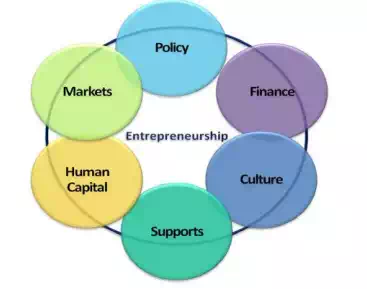

Many countries and international bodies (such as the EU) have attempted to promote growth-orientated entrepreneurship either through direct measures or indirectly through policy instruments (European Commission, 2002). It is therefore understandable that policy actors are most eager to benchmark and compare the national government policies for entrepreneurship. They wish to find examples of best practice in entrepreneurship policy design and identify recommendations for national governments. These goals also stand high in the agenda of the European Commission (Bodas Freitas and von Tunzelmann, 2008). Addressing these crucial issues becomes more complicated as recent studies have suggested that policy measures, instruments or design do not perhaps determine the success of policies, but it is a matter of finding a proper ‘fit’ between the policies and the entrepreneurial environment in which the policies are applied (e.g. Desrochers and Sautet, 2008). While addressing the development of an entrepreneur’s management skills is critically important to enable people to grow their business (if that is what they wish to achieve), enterprise support agencies and policy-makers must also consider how they can improve public policy, enable access to markets, provide hard and soft supports, create a supportive culture, and offer greater access to finance, if they are to engender a positive entrepreneurship ecosystem through which enterprises can flourish (as shown below in Figure 5). Training for the development of entrepreneurship skills for growth-orientated businesses would feature under Human Capital and Supports in the general entrepreneurship ecosystem.

Figure 5 – General Entrepreneurship Ecosystem

Detailed analysis by Inno-Grips (2011) of growth policies and programmes across many countries led the researchers to offer the following ten policy recommendations:

1. Policies supporting high growth of SMEs are worthwhile - it appears to be worthwhile to support high growth of enterprises in order to leverage the positive impact of these enterprises.

2. Seeking sustainable (high) growth - as high growth can also lead to high failure, the policy objective should be to generate sustainable growth.

3. Policies for general SMEs and for high-growth SMEs may coexist – since both types of policy generate positive returns for society, it suggests that policies for general SMEs and for high-growth SMEs should co-exist.

4. Broader approach to support high-growth – policies should not exclusively focus on specific aspects (e.g. finance).

5. No need to focus on specific industries - high-growth enterprises can be found in any industry and business ecosystems.

6. Creating the right framework conditions - policy makers should first of all set framework conditions right in order to prepare a fertile ground for winners to pick themselves.

7. Specific roles of the European Commission – the Commission’s main role could be to drive the further expansion and improvement of the Single Market (e.g. for venture capital) rather than launching specific measures for high-growth SMEs.

8. Enhance coaching opportunities - an infrastructure to encourage the replication of existing successful coaching networks throughout EU Member States could be set up.

9. Improve access to growth finance - improving the access to growth finance should be a priority for policy makers seeking to support high-growth SMEs.

10. Improve internationalisation opportunities - internationalisation of SMEs should thus be facilitated.

Since high growth frequently requires entry into larger markets, as national markets may be too small, the internationalisation of SMEs must be facilitated by the regional economic bodies (such as the EU) and by national governments. For example, this may include further work towards single markets in Europe as well as enhancing the European Commission’s Enterprise Europe Network. Items 1-5 are on a general level and thus apply to policy making on continental, national or even regional level; item 6 about legal framework conditions applies mainly to national policy but may partly be influenced by Directives, Recommendations and Communications by international organisations such as the EU; items 7-10 take a European perspective and require co-operation between European-level policy making with Member States. Overall, the report suggested that “policies should prepare a fertile breeding ground for SMEs to grow (e.g. by removing incentives to stay small), rather than trying to ‘pick winners’ and foster them”.

While the Inno-Grips (2011) report was able to identify a number examples of what the authors considered to be good practice regarding training for growth-orientated firms, the report concluded that there was a lack of evaluation studies that could substantiate the measures taken to support high-growth SMEs as being particularly effective or ineffective. Furthermore, the report found that policy makers face several challenges in drawing conclusions from existing research related to generating tailored support for high-growth SMEs which are as follows:

· Lack of empirical evidence

· Need for specific design

· Possible government failure

· Justification dilemma

· Resource allocation dilemma with general SME policy

· Quality limitations

· Speed limitations

· High growth co-occurs with high failure