Entrepreneurship Skills Required to Overcome Barriers to Growth

It is still a topic of much debate whether entrepreneurs are born or made. While it is generally acknowledged that there are natural ‘born’ entrepreneurs, there are also researchers who believe that entrepreneurship is a skill that can be learned. Drucker (1985) argued that entrepreneurship is a practice and that “most of what you hear about entrepreneurship is all wrong. It’s not magic; it’s not mysterious; and it has nothing to do with genes. It’s a discipline and, like any discipline, it can be learned.” If one agrees with Drucker’s concept of entrepreneurship, then it follows that education and training can play a key role in its development. In a traditional understanding, entrepreneurship was strongly associated with the creation of a business and therefore it was argued that the skills required to achieve this outcome could be developed through training. More recently entrepreneurship is being viewed as a way of thinking and behaving that is relevant to all parts of society and the economy, and such an understanding of entrepreneurship now requires a different approach to training. The educational methodology needed in today’s world is one which helps to develop an individual’s mindset, behaviour, skills and capabilities and can be applied to create value in a range of contexts and environments from the public sector, charities, universities and social enterprises to corporate organisations and new venture start-ups. Lichtenstein and Lyons (2001) argued that it is important for service providers to recognise that entrepreneurs come to entrepreneurship with different levels of skills and therefore each entrepreneur requires a different ‘game plan’ for developing his or her skills. Furthermore, they suggested that skill development is a qualitative, not quantitative, change which demands some level of transformation on the part of the entrepreneur.

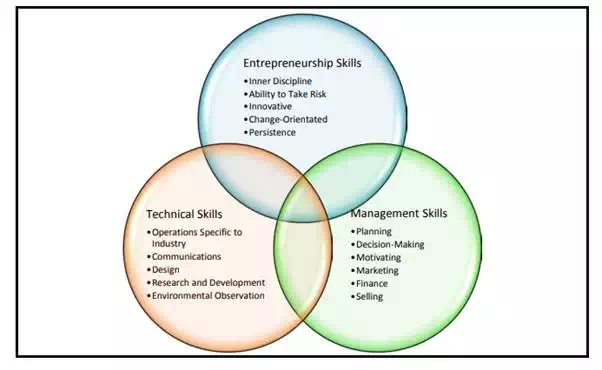

When considering all of the literature that has been published regarding the skill-sets required to be an entrepreneur, Figure 3 captures much of the essence of what many researchers have presented as key requirements. These skill-sets can be broken down into three groups: Entrepreneurship Skills, Technical Skills and Management Skills. The level of education and training required to develop each of these skills will be highly dependent upon the levels of human capital that individuals might already possess before embarking upon their entrepreneurial journey. Indeed it has been argued that developing these skill-sets will engender enterprising persons who should be equipped to fulfil their potential and create their own futures, whether or not as entrepreneurs (NESTA, 2008).

Figure 3 – Entrepreneurship Skill-Sets (Taken from Review of Literature)

Kutzhanova et al (2009) examined an Entrepreneurial Development System located in the Appalachian region of USA and identified four main dimensions of skill:

· Technical Skills - which are those skills necessary to produce the business’s product or service;

· Managerial Skills, which are essential to the day-to-day management and administration of the company;

· Entrepreneurial Skills - which involve recognizing economic opportunities and acting effectively on them;

· Personal Maturity Skills - which include self-awareness, accountability, emotional skills, and creative skills.

In examining the key skills required of entrepreneurs, O’Hara (2011) identified a number of key elements which he believed featured prominently in entrepreneurship:

· The ability to identify and exploit a business opportunity;

· The human creative effort of developing a business or building something of value;

· A willingness to undertake risk;

· Competence to organise the necessary resources to respond to the opportunity.

However, Kelley et al (2010) propounded that within any society it is important to support all people with ‘entrepreneurial mindsets’, not just the entrepreneurs, as they each have the potential to inspire others to start a business. Kelley argued that any educational training should enable people not just to develop skills to start a business but rather to be capable of behaving entrepreneurially in whatever role they take in life. This approach is quite broad but it captures the critical philosophy of modern entrepreneurship education and training programmes required if countries are to generate an increasing pool of people who are willing to behave entrepreneurially. But how one develops these skills and values, particularly with relevance to growth-orientated business activities, remains a question to which many researchers are still seeking an answer.

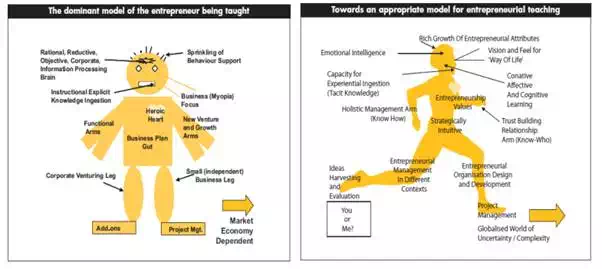

Figure 4 – Different Models for Teaching Entrepreneurship (Gibb, 2010)

According to Gibb (2010), the manner in which entrepreneurship is taught needs to be significantly altered as the traditional model of entrepreneurship is no longer applicable to the modern business environment. Gibb portrayed the dominant model of entrepreneurship as being static and focused heavily on the writing of a Business Plan and the various functional activities of an enterprise. His alternative ‘appropriate’ model portrays the entrepreneur as dynamic with a range of behavioural attributes that need to be developed. According to Gibb, this model embraces a number of key characteristics as follows:

· Instilling empathy with entrepreneurial values and associated ‘ways of thinking, doing, feeling, seeing, communicating, organising and learning things’.

· Development of the capacity for strategic thinking and scenario planning and the practice of making intuitive decisions based upon judgement with limited information.

· Creating a vision of, and empathy with, the way of life of the entrepreneurial person. This implies a strong emphasis upon the employment of educational pedagogies stimulating a sense of ownership, control, independence, responsibility, autonomy of action and commitment to see things through while living, day by day, with uncertainty and complexity.

· Stimulating the practice of a wide range of entrepreneurial behaviours such as opportunity seeking and grasping, networking, taking initiatives, persuading others and taking intuitive decisions. This demands a comprehensive range of pedagogical tools. • Focusing upon the conative (value in use) and affective (enjoyable and stimulating) aspects of learning as well as the cognitive as the relevance to application is of key importance (as is instilling motivation).

· Maximising the opportunity for experiential learning and engagement in the ‘community of practice’. Of particular importance will be creating space for learning by doing and re-doing. Projects will need to be designed to stimulate entrepreneurial behaviours and assessed accordingly.

· Creating the capacity for relationship learning, network management, building ‘know-who’ and managing on the basis of trust-based personal relationships. The Business Plan becomes an important component of relationship management leading to understanding that different stakeholders need ‘plans’ with different emphasis (a venture capitalist or angel is looking for different things than a banker or a potential partner).

· Developing understanding of, and building knowledge around, the processes of organisation development - from start, through survival to growth and internationalisation. This will demand a focus upon the dynamics of change, the nature of problems and opportunities that arise and how to anticipate and deal with them.

· Focusing upon a holistic approach to the management of organisations and the integration of knowledge.

· Creating the capacity to design entrepreneurial organisations of all kinds in different contexts and understand how to operate them successfully.

· Focusing strongly upon processes of opportunity seeking, evaluation and opportunity grasping in different contexts including business.

· Widening the context beyond the market. Creating opportunities for participants (students) to explore what the above means for their own personal and career development.