Synthesis and recommendations

Introduction

As stated previously, the aim of the ESoF study was to analyse the economic, political and cultural factors which hinder or foster the development of entrepreneurial skills and to develop strategies and tools that help to overcome barriers and support the development of entrepreneurial skills.

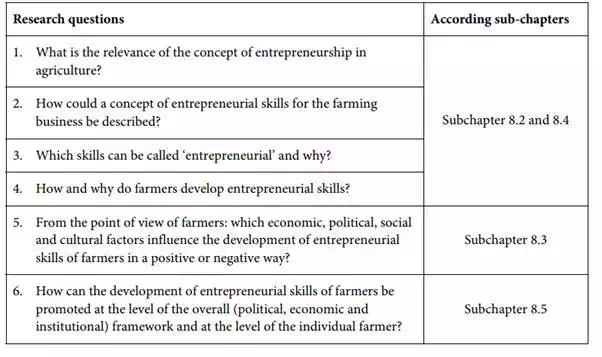

As the last chapter of this final report, this chapter interprets and synthesises all the work done in ESoF. This chapter summarises first the findings concerning the concept of entrepreneurial skills of farmers and continues by exploring the importance of this concept in a broader context, taking into account chapter 6 about Eastern European countries and chapter 7 about the policy context. The last section of the chapter describes recommendations regarding how to foster the development of entrepreneurial skills among farmers. The research questions described in chapter 1 are considered in this chapter as presented in Table 12:

Table 12: Research questions and according sub-chapters

A key concept of entrepreneurial skills for the farming business

In each of the chapters of this report, the ongoing political and economic changes in CAP and on the world markets have been emphasised as a crucial context for the ESoF project. This has been the background and starting point for all the project’s tasks.

In this respect, entrepreneurship is considered to be a means of meeting this challenge. In other words, entrepreneurship is seen in our study as a means of coping with the changes in the environment and thus contributing to the survival and success of farming businesses in the present as well as in the future.

In the entrepreneurship debate, perceptions of the concept of entrepreneurship as ‘establishing new businesses’ on the one hand or else seeing it from the point of view of growth orientation and cost reduction on the other are dominant. Interestingly, Porter (1980) equates both possibilities with competitive strategies, if the first is seen as a strategy of differentiation (see chapter 4). In fact, both strategies can also be found in the expert interviews in the pilot stage (see chapter 3). When asked explicitly about changes in the environment, experts in the pilot stage interviews listed them, but also emphasised what developments are consequently happening on the farms. They mentioned three strategies that are pursued by farms in order to cope with the new challenges in the environment:

· cost reduction and enlargement

· adding value to agricultural products

· non-food diversification.

In other words, the two competitive strategies outlined by Porter (1980) – low cost and differentiation – are also applied by farmers. Consequently, for the main stage interviews we chose farms that represent all three strategies and found that, in every case, farmers mentioned having entrepreneurial skills. Our conclusion was that all three strategies can represent entrepreneurial strategies (see chapter 4). However, in all three strategies, some farmers also presented themselves as being less skilled. This means that the strategy division per se is not the most important aspect, so that our initial hypothesis – that entrerpreneurial skills might be detemined by the strategic orientation of the farm business on farm (cf. chapter 1) – must be rejected. The more important point is that a strategy is pursued (consciously) at all. Pursuing a strategy consciously can already be seen as a way of coping with competition and thus as an expression of entrepreneurial behaviour .

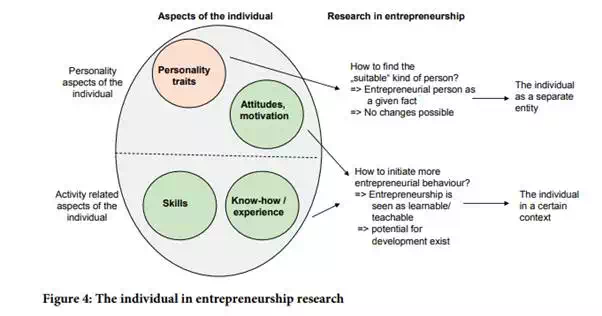

If entrepreneurial behaviour is required of farmers, the question arises as to how such behaviour is initiated. In the literature, two common perspectives exist which discuss how entrepreneurial behaviour is determined. One emphasises the personality of the entrepreneur and aims at understanding which personality traits determine entrepreneurial behaviour and success. Concepts such as need for achievement or locus of control form the focus here (Schiebel, 2002). From the personality traits angle, the person is seen as a separate, independent entity.

The other perspective considers the ‘activity’ side of the individual, which can be introduced, e.g., with the skill concept. Skills can be described as the best or proper way of carrying out tasks related to the farming business As such, skills emerge through the interaction of the individual (and his knowledge about the tasks) with the environment (application of knowledge in a certain context). Thus, the skill concept is a relational concept, connecting the individual with a certain context. The procedural nature of skills also implies convertibility and thus potential for development. This approach therefore constitutes a huge advantage in contrast to the personality traits approach, because personality traits are seen as stable dispositions (Gatewood et al., 1995).

The advantage of focusing on this aspect for the farming business is evident: given that it is becoming more complex to succeed in farming in the changing environment ,there is consequently a greater need for skills which support the actor in coping with the increased complexity. Fostering entrepreneurial skills can therefore be seen as one way of supporting farmers to succeed, since they constitute the activity-related aspects of entrepreneurship and, as such, are capable of being influenced.

The two ways of interpreting the individual are demonstrated in Figure 4.

These two points of view emerged both in the scientific literature and in the interviews throughout the project. Although we asked experts in the pilot stage which skills a farmer needs today in order to succeed in business, they also emphasised the role of inherent aspects such as personality traits and attitudes. The farmers interviewed in the main stage stressed in particular the relationship between inherent aspects and skills and confirmed the experts’ view that inherent aspects are important. However, when asked how they had developed their own skills and what could be done to foster the development of entrepreneurial skills among farmers, their arguments switched to the activity-related aspects. Finally, experts in the synthesis stage elaborated recommendations that pointed clearly to the activity-related aspects as well. Although they confirmed the importance of inherent aspects, the possibility of improving skills was also emphasised clearly within their recommendations.

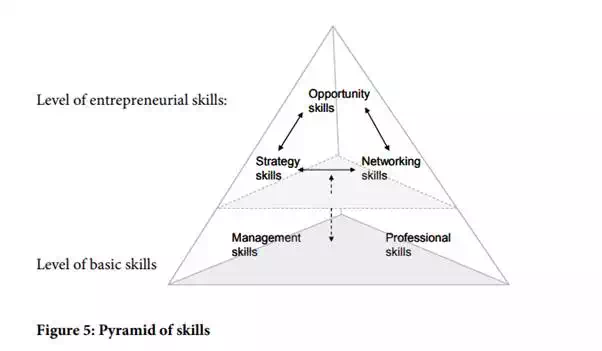

To foster the development of entrepreneurial skills it is important to understand which skills can be called entrepreneurial and why. When we asked experts in the pilot stage which skills a farmer needs today to succeed in business, they mentioned a long list, which was categorised by de Wolf & Schoorlemmer into 5 categories:

· Professional skills

· Management skills

· Opportunity skills

· Strategic skills

· Co-operation / networking skills

De Wolf & Schoorlemmer conclude that the last three categories can be called proper entrepreneurial skills, because they have to do with creating and developing a profitable business. Vesala (2008) develops this concept further by arguing that these three skills can be seen as meta-level skills, being more complex than professional (e.g. production skills) or management skills. According to Vesala, such complex higher level skills are called entrepreneurial not because they exclude something, but, on the contrary, because they necessarily encompass other skills. Therefore, entrepreneurial skills are actually skill sets. The category of networking skills, for example, contains communication skills, teamworking skills and cooperation skills (de Wolf & Schoorlemmer, 2007). In addition, networking and strategy skills serve the purpose of recognising and realising business opportunities. Thus, entrepreneurial skills are intertwined with and depend on each other.

The relationship between basic and entrepreneurial skills is shown in Figure 5.

Not only did the experts interviewed in the pilot stage list these skills, their importance was also made explicit by the farmers interviewed in the main stage. Furthermore, farmers were able to connect entrepreneurial skills with their daily experience; they recognise the skills as relevant to their business.

In other words, they work with these skills and most of them demonstrated having the skills, at least to a certain extent. However, there were also clear statements that there is still potential for improvement and that this would be useful, although some statements suggested that nothing should be done to foster actively the development of entrepreneurial skills.

One important conclusion concerning the development of these skills is that it is a learning process, as stated above. Furthermore, learning was associated in particular with experiential learning, with learning by doing and trial-and-error, not so much with the learning through formal education. A common perception in farmers’ statements was that learning entrepreneurial skills happens through a change of perspectives.

This means that learning happens when farmers are confronted with new ideas or different ways of doing things, which broadens their own perspectives. There are many different factors which support or hinder the change of perspectives: internal factors relating to the farmers (personality traits) and external factors such as new policy incentives, new market requirements or education, and – a third category linking the internal and external factors – networks and contacts. Networks and contacts (especially beyond the farming community) are crucial for finding necessary information and being confronted with different perspectives.

It was also emphasised that farmers themselves play an active role and take responsibility for their own learning. If we also take into consideration the fact that entrepreneurial skills are complex higher level skills, it follows that the acquisition of entrepreneurial skills cannot be taught in the same way as professional skills or management skills. The only way to initiate the learning of entrepreneurial skills among farmers is to strengthen the motivation of farmers themselves (enhance the learning process) and to optimise the learning environment by creating suitable opportunities to learn. This is confirmed by recommendations elaborated in the experts workshops and EU seminar of the synthesis stage, which contained suggestions for creating an optimal learning environment as well as incentives for farmers to take advantage of this environment, such as an exchange of experiences between farmers, discussions with customers outside the farming community, or travelling abroad.