How farmers are framed: beliefs and perceptions

In the debates about the regulation of food the role of the individual farmer is an issue (as ESOF demonstrates) that has led to wide ranging questioning about the entrepreneurial skills and/or qualities and/or values that EU farmers should possess or develop in order to meet new societal demands in terms of safety and environmental sustainability in food production as well as in economic and rural development terms. Various discursive definitions of the farmer’s role can be found in these debates, which offer parts of discursive repertoires (Potter, 1996) that societal actors can draw upon in their ‘framing’ (Goffman, 1974) of the agricultural entrepreneur. Examples are the farmer as rational agent, the farmer as victim, and the farmer as a social movement actor, to name but a few (see e.g. Tovey, 1997; Lockie, 2006).

Reference to ‘the entrepreneurial skills of farmers’ often occupy a prominent place in discussions of today’s European political strategies on food. However, on the basis of the analysis presented here we suggest that the discussion on entrepreneurial skills should be linked to a broader discussion of the framing of the role of the farmer in different settings and the changing roles attributed to contemporary European agriculture production. The picture of the framing and positioning of the farmer that the ESOF project produces seems to suggest that there is a need to talk about a plurality of issues and interests, and a plurality of farmers’ roles in a changing European context.

The different discursive ‘framings’ of the farmer are elements in negotiations among social actors over responsibility for particular agricultural and rural development policies. During such negotiations farmers are constructed in ways that create discursive repertoires other actors can use to position themselves and their own responsibilities. Thus the various constructions of farmers influence other actors’ institutional and organisational practices, making some solutions to agricultural production and rural issues more appropriate than others. This makes it important to clarify which kinds of construction of the farmers are in play; to understand, that is, which constructions are being used strategically in public discussion of the distribution of responsibility for defining agricultural and rural development problems and solutions.

Here, as an illustration, the role played by the Tuscan region and its innovative agricultural model and rural development plan in ‘framing’ the new role (qualities, values, skills) of agricultural entrepreneurs who will be protagonist of such a model is useful to note. Consensus over the main discursive framing is evident: the role of the entrepreneur as ‘the innovator within the Tuscan tradition9 ‘ appears to be largely agreed and almost ‘taken for granted’ in all of the interviews that were conducted for both the pilot and main phases of the project in Tuscany. Interestingly, the main discursive framing is very much linked to the priorities in the Regional Rural Development Plan, while the opinion that the new entrepreneurs should be increasingly independent from the financial support of the CAP and should be able to create or find their own niche markets emerge in many interviews.

This analysis indicates that there is a distinctive relationship between discursive constructions and organisational institutionalisations in the food sector. We have tried to describe the way in which this specific framing of the farmer/entrepreneur is related to the main political milieu and institutional setting, and, the shifting balances of discourses related to public and private responsibility for food issues.

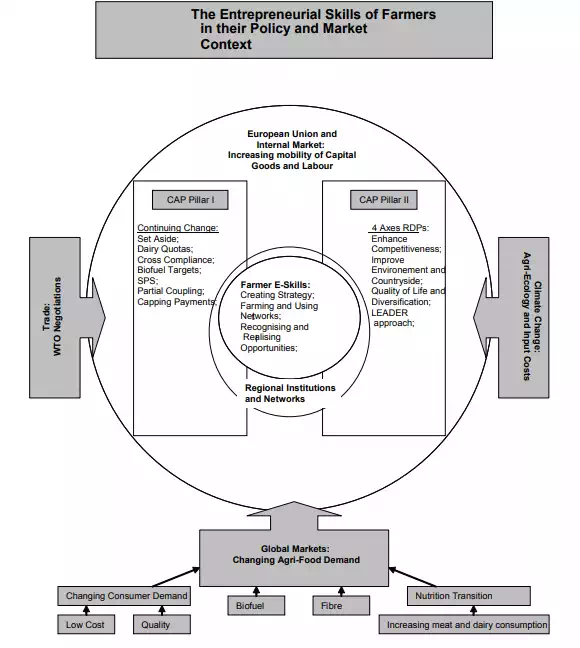

This chapter has attempted to relate the entrepreneurial skills of farmers to their policy and market context that extends from the Local and Regional to the European and Global environments. A complex set of influences impinge on the farmer and affect the farmer’s entrepreneurial skills and their development. Figure 1 illustrates some of the multiple levels and processes that are relevant to the farmer, and expresses the emphasis made in this chapter and throughout much of the ESOF project on how the entrepreneurial skills of farmers are realised within relational arenas. Inherent in these arenas are various framings of farmers and a major conclusion, therefore, is that farmers’ entrepreneurial skills can be both enhanced and be more effectively optimised if there are conducive framings of the farmer, and that these are supported by an effective regional institutional structure.

The study of farmers’ entrepreneurial skills has become significant following CAP reforms that may be traced to the early 1990’s, and which were given coherent form in Agenda 2000 and subsequent reform phases. The implication of these changes in policy has been that farmers become more autonomous as economic agents and should, therefore, develop new skills to enable them to manage and develop their businesses. Agriculture is being repositioned by CAP reforms, and the development of Pillar II provisions through the Rural Development Regulation has provided the opportunity for farmers to broaden their own business visions and to develop their entrepreneurial skills.

The ESOF project has examined the behaviour of farmers in six regions and countries across Europe, and whilst the full range of entrepreneurial skills have been found in each area, uneven development may be related to the social, cultural and institutional context within which farmers operate. Whilst entrepreneurial skills are learned as new perspectives are gained following the reforms of the policy frameworks that surround agriculture and rural development, these are mediated by local approaches to agriculture and rural development that is illustrated by the variety of Rural Development Plans and Programmes.

This variety suggests that more local approaches to agriculture and rural development are emerging while the overarching framework of the CAP (in the form of Pillar I) continues to be subject to change.

Agricultural and rural development policy in Europe is, however, evolving at a time when the global economic and physical environments are generating substantial and unpredictable new challenges. New and growing demand for food and non-food agricultural products will, on the one hand provide welcome new markets for farmers, while climate change (acting in part as a driver for new markets), to take one factor, will place increased stress on European farmers. The potential for increased volatility at both European and Global levels puts greater emphasis on the regional dimension, which may be seen to provide a protective (if porous) buffer that allows farmers the space and the opportunities to develop as entrepreneurial actors.

In the context of the ESOF project the questions that arise from this kind of discussion are related to the relevance of a Multifunctional and an integrated Rural Development approach within the kinds of futures suggested above. Are they to be overtaken by a new form of productivism that is to be less influenced by state policy and less related to other rural economic sectors? In more specific terms what will be the consequence for entrepreneurial skill development that is predicated on diversified businesses given global uncertainties and insecurities, how can the demands of multifunctionality coexist with the demands for land from biofuels, new markets and climate change, and how do regional institutional structures in different parts of Europe respond in ways that may sustain a local and diverse agriculture?

Figure 3: The Entrepreneurial Skills of Farmers in their Policy and Market Contex