Entrepreneurship Skills for Growth-Orientated Businesses

Introduction

Given the current economic challenges facing many countries across the globe, the notion of engendering greater entrepreneurial activity has become a prominent goal for many national governments. The relevance of entrepreneurship to economic development has been highlighted by many researchers (e.g. Davidsson et al, 2006) and it is now well-recognised that education and training opportunities play a key role in cultivating future entrepreneurs and in developing the abilities of existing entrepreneurs to grow their business to greater levels of success (Henry et al, 2003). According to the European Commission (2008), the aim of entrepreneurship education and training should be to ‘develop entrepreneurial capacities and mindsets’ that benefit economies by fostering creativity, innovation and self-employment. Indeed the role of SMEs in terms of growth, competitiveness, innovation, and employment is now substantially embedded in the activity of the European Commission with the publication in June 2008 of the ‘Small Business Act for Europe’ and the ‘Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan’ in January 2013. The concept of an entrepreneurial Europe, which promotes the creation and development of innovative businesses, has led many of the EU Member States to strengthen their SME policies since academics, politicians, and policy makers increasingly acknowledge the substantial contribution that entrepreneurship can make to an economy (Bruyat and Julien, 2001).

More globally, governments across the world are increasingly recognising the positive impact that the creation of new businesses can have on employment levels, as well as the competitive advantages that small firms can bring to the marketplace (Scase, 2000). Moreover, while entrepreneurship provides benefits in terms of social and economic growth, it also offers benefits in terms of individual fulfilment, with entrepreneurship now breaking through the barriers of class, age, gender, sexual orientation, and race. However, because the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth is quite complex, many different approaches to encouraging entrepreneurship have been applied by a wide variety of agencies, with enterprise policies varying from country to country. Additionally, some commentators (e.g. Storey, 1994) believe that it is just a minimal group of enterprises germinating rapidly who provide the real increase in jobs and therefore it is these firms which policy makers should be converging upon. But identifying how small businesses can be transformed into growth-orientated firms remains elusive and despite the magnitude of research on growth firms, researchers remain uncertain regarding why some firms grow and others do not when originating from similar circumstances. This paper seeks to identify what entrepreneurship skills are required to develop a growth-orientated business and how these skills might be enhanced.

Barriers to Growth

Part of the difficulty in achieving consensus regarding how to transform small businesses into growth-orientated firms originates from the inability to find a settled definition regarding ‘what is a growth-orientated firm?’ Having reviewed numerous research studies relating to high-growth firms, Hoy et al (1992) recorded that a wide variety of growth measures were used ranging from increased market share or enhanced venture capital funding, to growth in revenue, return on investment, or the number of customers of a firm. Within these studies, employment was generally the most accepted method of measuring growth. This occurs because the data is easily gathered, determined and categorised, and because this system is already frequently utilised to ordain firm size. Additionally, employment figures will be unaffected by inflationary adjustments and can be applied equally in cross-cultural studies, although difficulties may arise in determining how one measures part-time or seasonal employees. It is also worth noting that while a firm may increase its level of employment, it does not necessarily follow that it has expanded its market or financial success. However, it is now broadly agreed that if a firm is to achieve sustained expansion, it must satisfy a number of requirements for growth - it must increase its sales, it must have access to additional resources, it must expand its management team, and it must extend its knowledge base. But each set of requirements establishes a different set of obstacles for the entrepreneur.

Beyond this finding, the broader review of the literature identified that the key barriers to firm growth can be broken into two broad categories: Internal and External. These are detailed in Table 1 below with the most frequent barriers identified given under each category.

TABLE 1 – Barriers to Growth (taken from Review of Literature)

Table 1 highlights that a decision by a firm to grow its business is initially influenced a range of External Barriers (or influencing factors). Concerns about matters such as the availability of skilled labour, lack of competition, favourable government policy and economic climate, supportive legislation and easy access to markets all contribute to an entrepreneur / management team deciding to grow the business. However, a 2009 report by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation found that more than half of the companies on the 2009 Fortune 500 list were launched during a recession or bear market, along with nearly half of the firms on the 2008 Inc list of America's fastestgrowing companies. Examples of companies founded during a recession over the past century include: HP, Burger King, Fed Ex, CNN, Microsoft and MTV. This finding highlights that in contrast to popular opinion, a negative economic environment does not necessarily mean that one cannot achieve high growth with one’s business, although it does reduce the opportunity for growth.

In exploring the principal barriers to firm growth through a detailed review of the literature, there was broad agreement that the primary issues involved in growth are (1) motivation, (2) resources and (3) market opportunities. Indeed much of the literature highlights the central role of the business owner in determining future growth and that their attitude to growth may even influence the chances of firm survival. A study by Orser (1997) found that of the firms studied in her research, those firms whose owners had stated five years previously that they wanted to grow the business were now more successful, while the majority of firms owned by entrepreneurs who did not prioritise growth had either not grown or had failed.

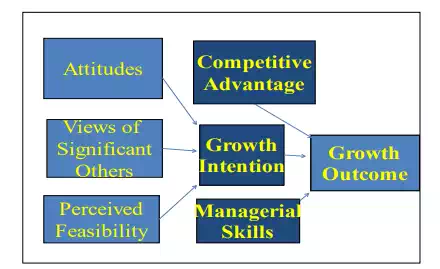

Figure 1 – Growth Intentions

Orser found that the growth intentions of an entrepreneur were influenced by their own attitudes, by the views of other people (such as their spouse, business partner, accountant or banker), and by the perceived feasibility of success. The attitudes of the entrepreneur were influenced by positive factors such as financial implications, contribution to the community and recognition of the community but they were negatively influenced by factors such as work-family balance, additional stress, and potential loss of control. The combination of these influences contributed to the accumulation on an entrepreneur’s growth intentions, which combined with competitive advantage and managerial skills determined the growth outcome of the firm.

Much of the literature reviewed agreed that the most significant barrier to growth was based upon psychological or motivational factors. If there is not a strong commitment by the entrepreneur / management team to grow the business, then it is unlikely to happen of its own accord. However, even if the commitment to growth is demonstrated, then issues such as management capability, funding, shortage of orders, sales / marketing capacity and poor product / service offering has also been featured in the literature as being the primary barriers to firm growth.

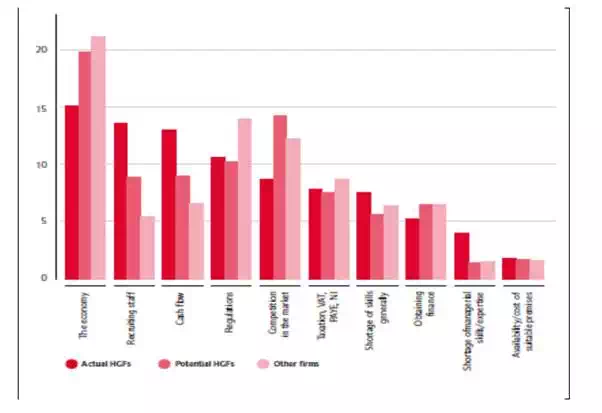

A study in the UK by NESTA (2011) is very informative in terms of how high-growth firms view barriers and challenges to growth differently to other firms (see Figure 2). Perhaps the most interesting finding from the study is that high-growth firms do not see the economy or competition in the market as a barrier to growth in the same way as other firms. Instead they see the ability to recruit staff and skills shortage, plus ensuring a positive cash flow, as being the critical issues in achieving firm growth. This suggests that high-growth firms are less concerned about what they cannot control but instead concentrate on those areas within the realm of their own activities.

Figure 2 – Most Important Obstacle to Firm Growth (NESTA, 2011)

In addition to the above results, there were a number of other findings from the literature review which also offered interesting insight, even if they occurred less frequently. Siegel et al (1993) found that growth firms were leaner with fewer managers, had slimmer payrolls, and used their assets more productively than non-growth firms. Evans (1987) evaluated the relationship between firm growth, size, and age for 100 manufacturing enterprises, and determined that firm growth, the variability of firm growth, and the probability that a firm will fail decreases as the firm ages. Evans also judged that firm growth decreases at a diminishing rate with firm size. Storey et al (1988) discovered that young firms were more likely to achieve greater profitability and grow faster than would old firms. These results help build a profile of growth firms and suggested that agencies should focus their energies on attracting younger firms who are lean and hungry for success.

The review of the literature also considered the reasons for firm failure since such a feature might offer some additional cues regarding the challenges that entrepreneurs face when building a business. The most frequently mentioned reasons for failure included: (1) the founder’s inability or unwillingness to change, (2) lack of management skills, experience and know-how, (3) not keeping complete and accurate records, (4) having little focus in activities (attempting to be all things to all people), (4) under-pricing, (5) underestimating competition, (6) ‘Mousetrap Myopia’ (the notion that the world beat a path to your door for having the best mousetrap), (7) poor marketing activities, (8) weak financial control, (9) lack of strategic planning, and (10) inadequate liquidity. Many of these causes of firm failure could also be identified as barriers to firm growth and therefore might be considered in any training needs analysis that is developed regarding engendering firm growth.

TABLE 2 - Factors Influencing Growth in Small Firms (Storey, 1994)

As previously stated, the review of the literature regarding barriers suggests that for highgrowth firms, the state of the environment is not the most important concern. Instead, the evidence would suggest that high-growth firms would view the primary weaknesses as being internal and within their own control to change. Storey (1994) sought to classify the key internal factors that influence firm growth under identifiable categories and suggested that instead of examining descriptive models, researchers should utilise prescriptive paradigms combining the following components: entrepreneur, firm, and strategy. As can be seen in Table 2, Storey identified the key elements to each component and argued that all components needed to combine appropriately for the firm to achieve growth. Less rapidly growing, no-growth or failing firms may have some appropriate characteristics in the entrepreneur, firm or strategy areas, but it is only where all three coalesce effectively that a high-growth firm will be found. Each component offers indicators of where weaknesses might exist in the alchemy required to create a high-growth firm.

It is clearly evident from a review of current entrepreneurship literature that entrepreneurship involves more than business start-up, and that it also includes the development of skills to grow a business, together with the personal competencies to make it a success. Gibb (1987) noted that while the entrepreneurial role can be both culturally and experimentally acquired, it is consistently being influenced by education and training. It has also been argued that the traditional approach to entrepreneurship (with its emphasis on business start-up) needs to change and that the relevance of entrepreneurship education and training must be expanded. Indeed it is now widely recognised that there is a requirement to move from traditional ‘instruction’ towards an experiential learning methodology, utilising an action oriented, mentoring and group-work approach to ensure greater learning effectiveness. Within this approach, critical thinking and problem solving are recognised as key skills, while it is also appreciated that skill development regarding risk-taking, innovation, creativity and collaboration needs to be valued more. A more hands-on approach is also required for the development of project management and budgetary skills. Therefore, increasingly it is being recognised that teaching entrepreneurship skills should be interactive and might include case studies, games, projects, simulations, real-life actions, internships and other hands-on activities. But using active learning methods requires highly skilled trainers and trust in involving participants more in the learning process, fostering innovation and creativity and learning from success and failure needs to be encouraged. It must also be recognised that the entrepreneurial skill development process occurs over a period of time and requires the active involvement of entrepreneurs (Kutzhanova et al, 2009).