Rural development plans: institutional contexts for entrepreneurial farmers

The Rural Development Plans that have been produced in each country, designed to respond to local economic, social and environmental conditions and needs, differ from each other in many respects (Dwyer et al, 2007), not least because the RDP are financed through joint funding arrangements between the EU and Member States5 . Pillar II differs fundamentally from Pillar I in this regard: whereas direct agricultural (coupled) aid does not need to be co-financed by Member States, all RDR interventions must (Shucksmith et al, 2005).

The spending on, and effect of, RDP measures in each Member State is also dependent on the complementary national funding and implementation capacity at national, regional and local levels. In their analysis of RDPs produced for the 2000-2006 funding period Dwyer et al (2007) note the variation in the structures and implementation of RDPs in Member States. Sweden, Austria and France, for example, applied single national plans; regional programmes were applicable in Germany, the UK and Italy; whilst Spain ran a complex mix of national and regional programmes (see also EC 2003b). In addition the use of the RDR varied widely between Member States and Dwyer et al conclude that Member States continued under the RDR the kind of rural development policies that had been previously applied on a national basis and based on local priorities that precede the establishment of the RDR. As Lowe et al also note there have always been national and regional variations on the main CAP reform, e.g. France had its policy centred on an ‘agrarian agenda’: promoting an

‘…agricultural form of multifunctionality..’

whilst the UK pursued a ‘..countryside agenda..’ focussed on the

‘…provision of broader environmental public goods for a society that places particular value upon them’ (Lowe et al, 2002).

The relationship between how agriculture is perceived and its place within wider economic development affects the context within which farmer entrepreneurial skills may be developed, and the variation in the ways that Member States have developed and organise their RDP indicate these connections. As an illustration the Tuscan and English RDP are briefly compared in the following section, suggesting that the development of farmer’s entrepreneurial skills can be greatly affected by regional or national understanding of agriculture, rural development and the local institutional context.

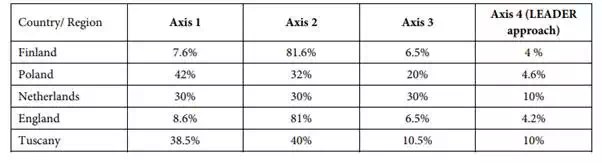

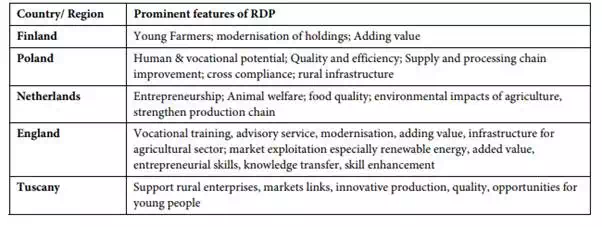

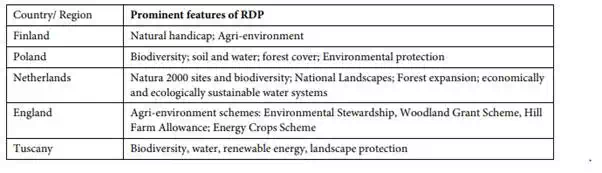

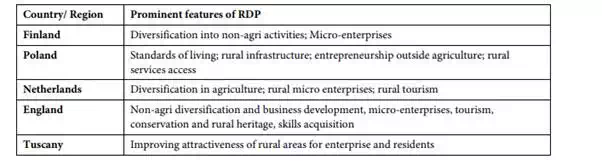

The distribution of funds across the three substantive Axes sets up the institutional context against which farmers may develop their businesses. A comparison of summaries of RDPs that have been submitted for the funding period from 2007-2013 provides a similarly varied picture of the intentions and priorities of current Member States. Table 8 below illustrates how the distributions of funds across the four RDP Axes vary for the five EU territories included in the ESOF project. Table 9 to Table 11 indicate the main areas that each RDP highlight for inclusion under each Axis, areas that have been drawn from a common list of measures defined by the RDR. The percentage sums in Table 8 indicate the share of the Rural Development budget that is allocated to each of the four Axes from the total budget applicable in each country or region including both Member State and EU (EAFRD) contributions.

Whilst it might be argued that activities supported by funding from each of the Axes may have effects on more than one substantive area, and whilst the influence of the historical approach to rural development in each country or region (Dwyer et al, 2007) may limit the scope for policy innovation in response to the new RDR (with the possible exception of Poland whose priorities are more concentrated on enhancing the human capacities of the agricultural and forestry sectors), Table 8 graphically illustrates the differences in national and regional priorities for rural development. Both Finland and England appear to have similar priorities, each placing the overwhelming majority of their resources under Axis 2 (improvement of the environment and countryside) whilst much lower proportions are allocated to funds that support the ‘competitiveness of the agricultural and forestry sectors’ (Axis 1) and that ‘enhance the quality of life in the countryside and diversification of the rural economy’ (Axis 3).

Table 8: Share (%) of total public expenditure (including EU contribution) in each country/region devoted to each axis

Table 9: Axis 1: Enhancement of the competitiveness of the agriculture and forestry sectors

Table 10: Axis 2: Improvement of the environment and countryside

Table 11: Axis 3: Quality of life in the countryside and diversification of rural economy

The other three regions and countries have decided on much more equitable distributions, and devote a larger share of their rural and agricultural development resources to those activities and programmes that may be expected to have more direct impacts on the skill levels of farmers and their opportunities for developing either new agricultural activities (Axis 1), value added activity or diversified businesses (Axes 1 and 3).

Greater funding for Axis 3 also suggests a greater commitment to developing the rural economy that does not necessarily directly depend on agricultural production. The impression given by the raw data from Table 8 is supported by the indication in Table 9Table 11which provide the main priorities of RDPs as highlighted by each Member State. These tables show a greater degree of heterogeneity in the detail of Member State priorities than the division of Table 8 into two contrasting approaches seem to suggest, although a full and rigorous analysis of the differences in priorities between states and between regions would require an analysis of the actual programmes undertaken in the 2007-2013 funding period.

What might also be taken into account in a more detailed analysis and comparison between RDPs is the structure and scale of agriculture and forestry, and the structure and degree of rural development in each country and region. The need for support for activities and capacities that are included under the different Axes is likely to be different in each country and region, while the impact and effectiveness of the percentage allocation of the local RDP budget to specific spending areas will vary according to the local context and conditions. Whilst taking these general caveats into consideration, it may still be instructive to make a further, if brief, comparison of two of the areas covered in the ESOF project that appear to have strongly contrasting approaches to the distribution of state support for agricultural and rural development, namely England and Tuscany.

The RDP6 for England (RDPE) has a budget of €3.9 billion for the period 2007-2013, more than doubling that of the period from 2000-2006 (DEFRA, 2007). As indicated in Table 8 above 80% is spent on measures under Axis 2 of the RDPE, and for England7 this covers expenditure on environmental stewardship schemes, woodland grant systems, hill land or areas of natural handicap assistance and specific schemes that include non-food production such as the energy crop scheme.

The emphasis of the English RDP on Axis 2 is justified by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) on the basis of three main considerations (DEFRA, 2007). The first is that the agriculture and food sectors in the UK is considered to be performing well, and to the extent that state support is required that these needs are catered for by existing schemes. The sector as a whole is, therefore, believed to be less in need of support through Axis 1 or Axis 3 initiatives, suggesting that there may be a bias in the policy approach toward the larger (and) conventional producers (in ESOF terms) rather than toward those farmers who are consciously searching for ways of improving their income through value added or non-food diversification projects. Secondly DEFRA notes that the needs of the rural economy in England are sufficiently addressed by government initiatives that do not differentiate between rural and urban economies. The third consideration, therefore, is that the emphasis of the RDPE is put on those policy areas that may not be sufficiently supported by more general government assistance viz. good environmental land management, on which both the agriculture and forestry sectors and wider rural economies depend for their sustainability.

DEFRA, in response to criticism that Axis 2 payments may be skewed toward enhanced farm incomes, contend that the economic impact of these payments will have both direct and indirect employment benefits deriving from the expenditure on agri-environment and forestry schemes. However, the focus of the RDP and institutional support appears to be on addressing some multifunctional impacts of agriculture without making an explicit attempt to enhance the multifunctionality of agriculture in rural development terms. This view of the approach in England is noted also in findings from the EU’s FP6 Multiagri project where Marsden and Sonnino question the commitment of DEFRA to the support of a multifunctional agriculture that is integrated to rural development (Marsden and Sonnino, 2005).

For Tuscany the RDP allocates €914m Euro with roughly equal division of resources between Axes 1 and 2 while Axis 3 receives a tenth of the total funding. For Axis 1 (€403m) the focus is on modernisation of agricultural businesses, whilst Axis 2 (€337m) focus is in conserving biodiversity, safeguarding water resources and reducing water contamination in order to promote energy conservation and development of renewable energy sources. Analysis of the expenditure distribution for the first RDP in Tuscany covering the period up to 2006 suggests that emphasis was on measures aimed at improving the environment and the rural territory, but also on measures such as the commercialisation of quality products that stress the particular link between products and the territory (OECD, 2005). This approach has been crystallised into the so-called ‘Tuscan Model’, which is the basis for the new RDP and which highlights an emphasis on small and medium sized farms, an emphasis on quality products, diversification in production and of the role of women in this activity, whilst regarding the physical landscape as an element to be integrated into a total agri-food offer by which food production and tourism may mutually benefit (see discussion on the Tuscan Model in, for example Morgan et al, 2006).

Emanating from the Tuscan example is the belief that supporting and developing farmer’s entrepreneurial skills implies sympathetic local development policies, which should be informed by perceptions of how a region will position itself and develop. The research carried out by ESOF on the Tuscan region suggests that an agreement obtains between stakeholder opinion (pilot stage), the business development pathways that the farmers take (as illustrated in the main stage), and the policy framework that is indicated through the Tuscan RDP. This has been shown not to be manifest in the same way in other case study areas, and these differences reinforce the treatment of entrepreneurial skills as embedded in local cultural and institutional context and oriented by locally developed policy frameworks.