Farmer behaviour and the uneven distributions of farmers’ entrepreneurial skills

The ESOF project responds to the perception that the trajectory of CAP reform, the increasing integration of agricultural and rural development policy, and the changing nature of the marketplace will require the farmer to be more independent of state support and guidance and to exercise greater relative autonomy than the CAP has hitherto demanded. Such expectations increase the importance of the farmers’ business skills and increase the focus on the capability of the farmer to act in an entrepreneurial fashion. A programme of entrepreneurial skill development, informed by the understanding of these skills and the context in which they are expressed that emanates from the ESOF project, might be expected to increase the relative autonomy of farmers and help them to cope with changes in agricultural and rural development policies; to be less dependent on state support; and to be more capable of responding to the uncertain futures that awaits the agri-food sector.

Whilst entrepreneurship was recognised as a multi-faceted concept, and understood in a number of different ways (McElwee, 2005), an exploration from the perspective of entrepreneurial skills is based on an understanding that entrepreneurial skill and behaviour are things that may be learnt. From this perspective, entrepreneurial skills are not seen as limited to those who have what might be termed an inherent capacity, or who have advantageous environmental or physical conditions. According to the results of the ESOF project, any farmer may be shown to possess entrepreneurial skills regardless of their particular situation and the type of farming in which they are engaged, although the level of skills may vary and the skills may be manifested in different ways (Vesala and Pyysiäinen, 2008). And the project also finds that farmers were capable of recognising and relating the three skills identified by the research project to their own knowledge, experience and activities in each of the six regions. Variations in the degree of skilfulness could be ascertained among farmers in each country, together with different awareness of skill levels and accuracy in the farmers’ self-presentations.

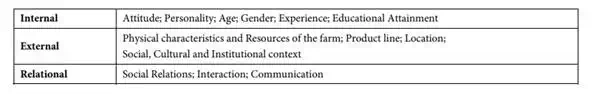

In all the country and regional reports and for each of the three types, farmers accepted the relevance and importance of entrepreneurial skills to their own businesses, a response that may be interpreted as a favourable attitude toward these skills. However, many farmers also noted their own deficiencies, whether in possessing or in being able to deploy one or more of these skills. Explanations by the farmers for the uneven distribution of entrepreneurial skills were based on factors that were internal, external and relational as summarised in Table 7.

Table 7: Explanatory factors affecting uneven distribution of Entrepreneurial skills

Internal factors include personal features of the farmer such as attitude and personality, age, and gender as well as experiential characteristics (e.g. work history outside farming or away from the family farm), educational attainment and training. External factors on the other hand are related to the context in which the farmer works, including the physical characteristics and resources of the farm, the specific type of production undertaken (which may allow a greater or lesser degree of flexibility and opportunity for innovation), and the physical and geographical location of the farm. External factors include the social and cultural context of the farmer, the degree of their embeddedness in this milieu, and the institutional context, with attendant opportunity for support and development of farm and off-farm enterprises. With respect to the latter factor, farmers relate to the politico-economic environment that the institutional environment produces in differing ways with similar specific processes or measures impacting farmers in different ways. Differences also arise between regions and countries because of different local institutional arrangements and their influence on the farmer, as illustrated by variety in Rural Development Plans and approaches, a feature that is discussed further below.

Relational factors affecting the farmers’ ability to develop entrepreneurial skills refer to social interaction and communication, particularly relevant for ‘Networking’ skills and the skills of ‘Recognising and Realising Opportunities’, but also indicative of the ways by which the physical, social or institutional context of the farm and the farmers interact to create the environment for entrepreneurial activity. Relational factors, therefore, bridge Internal and External factors.

Developing entrepreneurial skills among farmers

Farmers’ understanding of entrepreneurial skills, as conveyed through their interview responses, also include comment and implications related to the way that these skills are developed. What is strongly employed in discussion of Internal, External or Relational factors is the idea of entrepreneurial behaviour as a set of skills that may be learnt. Whilst structural features and conditions, such as personal characteristics or policy environments, are quoted as relevant and important preconditions that affect the opportunities that farmers have to engage in learning events, the learning processes themselves are recognised as important, and confirm the view that entrepreneurial behaviour is not dependent on inherent characteristics of either the individual or of the context.

This view of entrepreneurial behaviour as a set of skills that may be learnt has implications for the way that they may be developed and encouraged. A common finding from the project in this respect is that entrepreneurial-skill learning processes across all farmer types in all countries or regions are related to the effect of new or contrasting perspectives provided either by the farmer or by changes in market, institutional or social contexts. Hence, diverse work experiences, personal histories gained outside the farming sector, educational attainment, and diversity in contact type and in networks may contribute to providing new perspectives, as can change in social and cultural conditions and contexts, new visions of the marketplace and of marketing opportunities and, particularly relevant for the focus of this chapter, new farmer-related policy incentives. These influences encourage changes in mindset and habits of thought and, hence, encourage farmers to explore their capabilities and their business identities through an entrepreneurial approach that include awareness of strategy, the value of networking and use of contacts, and the confidence and motivation to realise business opportunities.

A major implication of the view of learning by change of perspectives is that the farmer should be considered as an active subject in the learning process. External actors create and offer opportunities and stimuli for learning, but clearly cannot guarantee nor enforce learning success. Development of entrepreneurial skills is dependent on the individual, a finding that matches with the widespread notion that associates entrepreneurship with individualism (McElwee, 2005), but is in association with entrepreneurial skills that embed the farmer within relationships with other actors. Individual learning and skill development is, therefore, contingent on particular sets of conditions, attributes and motivations and may be recognised in the specific pathways individual farmers take that illustrate their entrepreneurial skills.

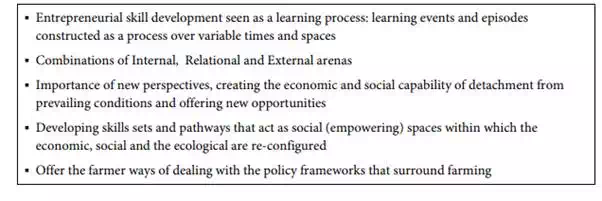

An interpretation of ESOF findings, and some of the implications related to entrepreneurial skill development from ESOF, is presented in Box 2. These features may form the basis for developing farmers’ understanding of how to improve their own entrepreneurial skills in addition to offering an opportunity to integrate an entrepreneurial skill based perspective with agricultural and rural development reform.

Box 2: Features of Entrepreneurial Skills Development