Special situation of Eastern European Countries

General introduction to land ownership during socialism

A few years after World War II, very unfavourable changes in the ownership structure of agricultural land took place in those European countries that found themselves in the area of influence of the former USSR. Following the Soviet model, state-owned farms and collective farms were established on land confiscated from its previous owners. The process of collectivisation brought about chaos and disorder as well as a very large reduction in the commercial production of food per unit area. This was due to the fact that, in the new situation regarding ownership, the quality of land cultivation worsened and the means of production were allocated centrally. The supply system was not always appropriate to the needs that arose from the nature of the production carried out, so that the means of production were often wasted.

Moreover, the large size of the newly established state-run farms, often covering more than 10 thousand hectares, created great difficulties in effective management, which was made worse by the lack of qualified managers and a generally low level of worker competence. The activities of sowing or planting on such farms were planned by a superior authority. The planning was often carried out without recognising at all the feasibility of growing crops in a given area in view of, for example, the unfavourable soil and climatic conditions existing there. Also, no consideration was given in the plans to the proper requirements regarding manpower and farm machinery. Moreover, when implementing proposals for growing a particular crop, harvest dates, transport requirements and storage facilities needed for the produce were very often not taken into consideration. More often than not, the state farms were simply unmanageable and were burdened with a large deficit. However, for purely ideological reasons, in contrast to privately-owned farms, e.g. in Poland, they were supported financially every year from the central budget.

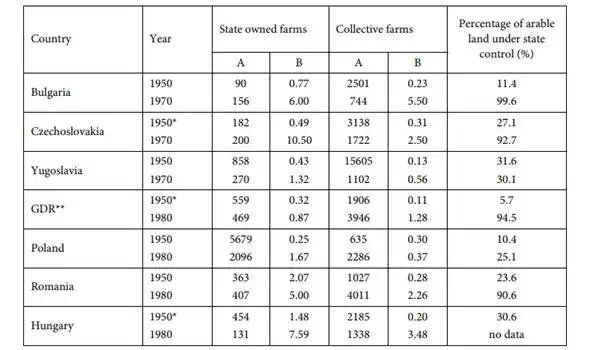

It should be emphasised that in countries such as Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania a vast majority of agricultural land came into the possession of state controlled farms because of strong political pressure from the top. The percentage of those farms in the latter stages of the changeover, which happened towards the end of the 1960s and 1970s, depending on the country, ranged from about 91% to 99% of the total arable land. In Ukraine, state ownership of the land was almost 100%. The same situation existed in Moldova and Belorussia. Poland was the only country in which this figure never exceeded 25.1%. In the former Yugoslavia it was 30%. However, in the latter two countries there were a large number of small farms (Table 5).

Table 5: State controlled agriculture in selected countries of Central Europe, 1950-1980

In the majority of cases, collective farms and state farms were inefficient in the production of agricultural produce. Even those that seemed to carry out production at a higher, economically fully accountable level turned out to be unprofitable. Poor utilisation of the available resources resulted in a constant shortage of food products in the former Eastern Block countries. Even the regions of fertile soils, from which food had been exported before World War II, became importers of food as a consequence of the implementation of the principles of a planned socialist economy in agriculture.

Transition of agriculture to the free market economy

This state of affairs persisted until the beginning of the transformations that began in Eastern and Central Europe towards the end of the 1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s. The political changes that have altered the image of the European continent are associated with the collapse of the communist system and the introduction of the market economy.

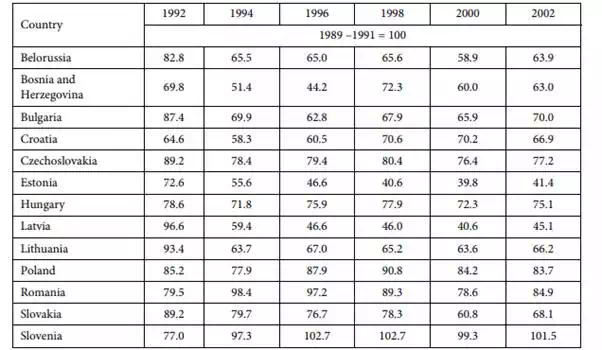

In the case of agriculture, the changes proved to be more difficult than in the other sectors of the economy. Agricultural production carried out under the conditions of drastically reduced subsidies, the necessity to purchase the means of production at market prices, and the struggle to maintain a presence in a competitive market full of imported goods suddenly decreased in almost all of the affected countries. In extreme cases, the drop in agricultural production was more than 50% compared with the situation before the changes. A relatively small impact was noted in Slovenia, a small country in terms of arable land area. Agricultural production in Slovenia in the fifth year after the break-up of Yugoslavia was already higher than it had been during the period when the region was part of the Federation. This may be due to the fact that almost 100% of arable land in Slovenia is currently privately owned (Table 6).

Table 6: Changes in the total agricultural production in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe in 1992-2002

Privatisation and re-privatisation processes are well under way in most countries of the former Eastern Bloc, and the area of agricultural land that is not yet privately owned or leased is constantly shrinking. In 2007, state controlled arable land in Poland constituted less than 5%. It should be emphasised that in the initial stages of the changes in land ownership, particularly in 1989-1993, many difficulties were caused by the lack of experience in those kinds of operations.

In 1989-1991, the rational reasons (in the opinion of the Polish government) for restructuring and privatising state-run agriculture were responsible for spontaneous bankruptcies of state farms, colossal debts, a deterioration in economic performance, a complete production stop at times, an increase in the area of the land lying fallow, and many difficulties with an efficient, long-term development of agricultural real estate that for decades had been adapted to large area farming.

In most of the countries, many legislative, economic, organisational and social barriers emerged during the transformation, indicating total unpreparedness for the processes of restructuring and privatisation, which later had measurable negative economic, social and spatial consequences. Of these, the most important in Poland were: the capital barrier, resulting in a lack of demand for land, a still poorly developed credit system, no consideration for the regional variations in the supply of post state-owned farmland in relation to existing demand, a lack of tradition and interest in running family-owned farms, no reprivatisation act, difficulties in changing ownership rights (no documentation of land or property rights), and long periods of time needed to develop restructuring programmes. Similar problems occurred in the other countries of the region.

Following the privatisation or leasing of large farms there has been - not only in Poland - a significant extensification of agricultural production. The share of labour and capital-intensive crop production, oriented towards growing grain crops, particularly wheat and, more recently, maize and rape as well, has increased. There has also been a decline in animal production, especially in breeding cattle, as well as in milk production. The successors of state farms, in trying more effectively to adapt their activities to market conditions, have been driven by the market-imposed need for production cost effectiveness and maximisation of profits. Grain monoculture and cultivation based on prolonged mineral fertilisation only can, however, contribute to a decrease in soil fertility and a deterioration in farming conditions in the future. Such activities are mainly due to a lack of capital for investments for both long-term and current production (W. Guzewicz et al., 2002)

Apart from the problems with land previously managed as state-owned or collective farms, there have been great difficulties in the development of privately-owned farms. In most cases, privately-owned farms are too small in terms of the marketable yields they produce. The profits they are capable of generating are insufficient to allow people to live solely off the land, let alone create possibilities for investment. In 2005, as many as 69.4% of the farms in Poland were classified in the range of 0-2 ESU (European Size Units), and only 18.8% of the farms were above the level of 4 ESU. Taking into consideration only those farms which exceeded 1 ESU, the average economic size of a farm in Poland was 7.2 ESU. In the EU, the average for 2003 was 21.4 ESU, in Lithuania 3.8 ESU, 7.8 ESU in Greece, and up to 95.7 ESU in the Netherlands.