Results

One general observation in the main stage of ESoF was that the concept of entrepreneurial skills as it was used in this study appears relevant in the farm context. The importance of these skills was consistently accepted in qualitative interviews and also confirmed in the additional survey. Considering the distribution of the responses, both in the interviews and the survey questionnaire, the construct seems methodologically valid.

In this section we first sum up the overall results of the analysis of the self-presentations, related to research questions 1-3. Then we sum up the overall results of the analysis of the explanations for the development of the skills (questions 4-5), and finally comment on the results from a comparative perspective (questions 6-7).

Concerning the first research question, about how the farmers presented themselves in regard to entrepreneurial skills, a quite consistent pattern in the self-presentations was observed in all countries: in most cases the farmers presented themselves at least as a moderately skilful farmer. The farmers were typically able to connect these skills to their own farming activities and experiences in one way or another. Cases where the farmers were not able to connect these skills to their own activities remained exceptions in all countries.

A related pattern was also detected in all countries: in each country, there existed variation in the degree of skilfulness that was presented in the comments. There were, on the one hand, farmers who showed no hesitation in assessing themselves as being good in using these skills, and on the other hand farmers who hesitated in whether they really would assess themselves as being good in these respects. Another, related characteristic was the observation that, on closer inspection, the convincingness of the farmers’ presentations did not always coincide with their own skill assessments; some assessed themselves as being good but did not provide much convincing evidence to support their claims, whereas others assessed themselves as only moderately skilful but were nevertheless able to present rich and diverse examples of the manifestations of the skills in their business activities. Considerable differences in the convincingness of the skill presentations were observed. Hence, only a more detailed examination of the self-presentations allowed the researchers to detect the variation in the skill presentations appropriately.

This variation in self-assessments detected in the qualitative analysis corresponds roughly to the distribution of self-assessments observed in the additional quantitative study which was conducted in Finland. In the latter data, statistically significant but relatively small differences between conventional farmers and those with business diversification were observed, indicating better skills in the latter group.

On the basis of qualitative analysis, such a difference between subgroups cannot be argued for. After examining the distribution of the variation in skilfulness across the three strategic orientations (conventional, value added and non-food diversification), we can also address the third research question in part by concluding that the variation in skilfulness does not coincide with the division into three subgroups of farmers, made according to the strategic orientation. In other words, in each subgroup one can find skilful as well as less skilful self-presentations.

However, with regard to the second research question, about how these skills manifest in the self-presentations of the farmers, we could observe that the three strategic orientations do make a difference. To put this consistent finding simply: in all countries there were clear differences between the subgroups in how the skills manifest. Also the group-specific patterns in the manifestations of the three skills were quite consistent in all countries, although there were exceptions and the division of strategic orientations into three subgroups was not always clear-cut. The manifestations typical to the groups can be summarised as follows:

In conventional production, the manifestations of the strategy skill included two basic alternatives, either scale enlargement or a cost reduction strategy. In some cases these could be presented as existing in the activities as a combination. The importance of long-term decisions was also typical to the manifestations of the strategy skill in this group. In the manifestations of networking and contact utilisation skills, the contacts within the farmer community were emphasised; contacts and networks beyond other farmers and conventional actors in the agri-food sector were scarce. The manifestations of the opportunity recognition and realisation skills were typically connected to the production arena; market arena activities were typically included only indirectly in the manifestations, if at all.

In the subgroup of value adding business, the manifestations of the strategy skill included the adding of value to products as a core idea. This typically implied that short-term adjustments in production, product structure and market and customer relationships were emphasised. Also product development was commonly included as an element in the manifestations of the strategy skill. In the manifestations of networking and contact utilisation skills, contacts and networks beyond the farmer community were typically included. Emphasis was on the potential opportunities which were generated through access to networks and utilisation of contacts. The manifestations of the opportunity recognition and realisation skills were typically connected and integrated to the market arena as well as to production. Generally, the very idea of a value adding strategy seems to be grounded to some extent in the realisation of opportunities by means of market arena activities (marketing, realising a niche-product, promoting sales etc.).

In the subgroup of non-food diversification, the basic element in the manifestations of the strategy skill was the combining of primary production with some other non-food business activity, often in order to search for synergy between the activities. Also short-term adjustments in the steering of the business and product development efforts manifested often in the strategy skill presentations, but not necessarily. Customer segmentation, in turn, was an essential feature in the manifestations of this group. On the one hand, it manifested in the demonstrations of strategy and opportunity skills, e.g. as an incentive to start providing a certain service or product for a certain customer segment, and on the other hand it manifested in the demonstrations of networking and contact utilisation skills, as a factor that often drove the farmers to engage in networking and contact utilisation beyond the farming community (e.g. other entrepreneurs, customers outside the farming community, advisors and service providers, experts and suppliers). The manifestations of the recognised and realised opportunities were typically connected or integrated with the market arena as well as with production; market arena activities were often – but not necessarily – involved and the recognised and realised opportunities often touched upon both primary production and non-food business activities (e.g. allocation of workforce between the activities, recognising multiple uses for farm resources and machinery).

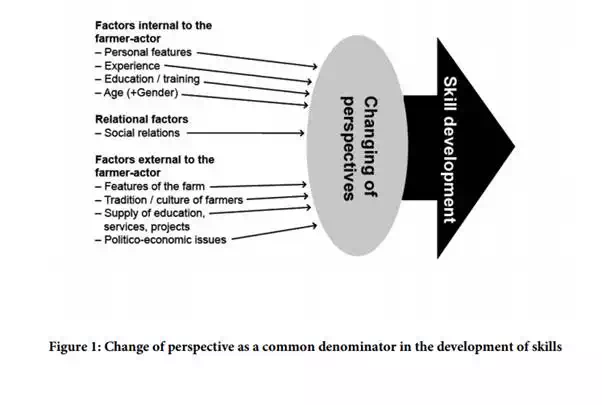

The fourth research question in this work package was: How do the farmers explain the development of entrepreneurial skills among farmers? Concerning such attributions (explanations of cause) on a general level, the attributions of skill development resembled each other across countries in two respects.: First, in all countries, a variety of attributions of skill development were made. The diversity of attributions could be captured with the help of a categorisation in which the attributions are divided into three general categories: internal (e.g. experience, age), relational (e.g. interaction with colleagues) and external attributions (e.g. features of the farm, targeting of subsidies) of the development of skills. Second, in all countries the suggested explanations involved contradictory evaluations, i.e. one and the same factor (e.g. market liberalisation) could be presented as an enhancing factor by one interviewee and as a hindering factor by another. In this sense, in addition to common categories of attributed factors, no simple and overarching explanation pattern could be observed in any of the countries.

However, it was possible to identify a common denominator that characterises the variety of explanations in each country as well as the explanations across countries as a whole. This denominator concerns the nature of the process of skill development. If the variety of internal, relational and external attributions is viewed from the perspective of the nature of the implicated skill development process, we recognise that the idea of learning is commonly rooted in the core of all types of accounts. When the interviewees presented justifications for their view that particular factors affect the development of skills, they did it by constructing the process as a learning event, regardless of the type of cause that was presented as crucial for the process to take place. This is an important observation, since the idea of skill development as a learning process was not suggested to the interviewees by the interview questions; instead, the interviewees themselves consistently chose to view the development of skills as something that takes place through learning.

The interpretation of skill development as a learning process revealed a further common denominator concerning the mechanism of skill development: across the various types of attributions (internal, relational, external), a learning event is constructed as a process in which the farmer is exposed to new perspectives. The importance of new perspectives came across in a variety of forms: the idea was implicated in explanations that emphasised the importance of a proactive attitude; diverse work experiences; work history outside farming; thorough farming know-how; education and training; diverse networks and contacts; stimulating farm context, culture and surroundings; motivating market visions and policy incentives. Virtually all explanations could be associated with the idea of being exposed to fresh perspectives, changes in habits of thinking or alternative ways of doing things. Facilitating factors functioned to introduce the farmer to novel perspectives and distance her from the habitual ones, whereas the hindering factors tended to prevent the farmer from reaching fresh distance to her activities and accessing novel perspectives. This concluding synthesis of the change of perspective as the common denominator and mediating mechanism in the learning of the entrepreneurial skills is depicted in Figure 1.

A common feature to the factors in the above-mentioned internal, relational and external explanations was that they may all manifest as factors that either enhance or hinder the development of skills. Hindering, for example, could be conceived as the absence of some enhancing factor, and vice versa. As already mentioned, interviewees also presented alternative interpretations regarding the importance and effect of particular factors on the development of entrepreneurial skills.

The sixth research question concerned the relation between farmers’ vie Work package points and those of outside experts or stakeholders. Experiences from the workshops with local experts, reported in the country reports (Vesala & Pyysiäinen 2008), seem not to bring out any serious doubts concerning the validity of our general conclusions as such. Many of the experts pointed out the nature of the data, of this being a qualitative case study, and cautioned against simple generalisations; however, the results as such were considered credible and understandable. Words such as training, education, advisory services, networking, exchange of ideas and so on are repeated in the recommendations provided by the workshops, underlining the crucial role of the learning process.

Some of the experts pointed out that there are also other skills involved in the farm business, in addition to the entrepreneurial skills studied here. For example, various managerial skills were mentioned. Related to this, one of the comments by the advisory board members is worth noting. This comment was about the minor role of management issues that are connected with the growth of the business and managing a larger enterprise unit, e.g. with several paid workers. Indeed, skills of realising opportunities and utilising contacts could also manifest in this area in the farm context, and do so increasingly in the future, but this aspect of entrepreneurial skills was not emphasised in the selfpresentations and explanations provided by the farmers interviewed in this study. One could speculate on the reasons for this by referring to the nature of the sample, or even to the possibility that the interviewed farmers in general were not inclined to view labour force, personnel and organisation management tasks in terms of entrepreneurial skills.

The seventh research question concerned the similarities and differences of the results between the six countries. The nature of the study as a qualitative comparative case analysis implies that, understandably, there are differences and variations between country reports. As already stated, the conclusions presented in this chapter aim to capture patterns that are common to all reports and to link them together. Thus, country or case-specific features have not been the focus of comparison. This is not to say that such features may not exist or be relevant. In the country chapters the reader will find some discussions concerning them (see Vesala & Pyysiäinen 2008). However, some examples deserve comment here. In the Dutch report one of the special features is that the analysis of the self presentations is organised so that the three strategic orientation groups have each been divided into subgroups according to further strategy-based divisions. Thus, among conventional farmers the Dutch researchers also distinguish farmers who are actively engaged in marketing and customer relationship management. On the one hand, this example shows that the dividing line between conventional farmers and value adding farmers is not so clear-cut. On the other hand, it seems to demonstrate that the manifestations of the skills are not by necessity confined to the production arena even among the conventional farmers, although such a pattern is dominant at the level of cross-nation comparison. One could further add that this exception (which by no means calls the pattern itself into question) is understandable in the light of the Dutch national situation, in which entrepreneurship has been actively promoted on farms, and horticulture, for example, has been a forerunner in this area.