Physics of Musical Instruments

Resonance

The goal of Unit 11 of The Physics Classroom Tutorial is to

develop an understanding of the nature, properties, behavior, and

mathematics of sound and to apply this understanding to the analysis of music

and musical instruments. Thus far in this unit, applications of sound wave

principles have been made towards a discussion of beats, musical intervals, concert hall acoustics, the distinctions

between noise and music, and sound production by musical instruments. In Lesson

5, the focus will be upon the application of mathematical relationships and

standing wave concepts to musical instruments. Three general categories of

instruments will be investigated: instruments with vibrating strings (which would

include guitar strings, violin strings, and piano strings), open-end air column

instruments (which would include the brass instruments such as the trombone and

woodwinds such as the flute and the recorder), and closed-end air

column instruments (which would include some organ pipe and the

bottles of a pop bottle

orchestra). A fourth category - vibrating mechanical systems (which

includes all the percussion instruments) - will not be discussed. These

instrument categories may be unusual to some; they are based upon the

commonalities among their standing wave patterns and the mathematical

relationships between the frequencies that the instruments produce.

Resonance

As was mentioned in Lesson 4, musical instruments are set into vibrational motion at their natural frequency when a

person hits, strikes, strums, plucks or somehow disturbs the object. Each

natural frequency of the object is associated with one of the many standing wave

patterns by which that object could vibrate. The natural frequencies of a musical

instrument are sometimes referred to as the harmonicsof the instrument. An instrument can be

forced into vibrating at one of its harmonics (with one of its standing wave

patterns) if another interconnected object pushes it with one of those

frequencies. This is known as resonance - when one object vibrating at the same natural

frequency of a second object forces that second object into vibrational motion.

The word resonance comes from Latin and means to

"resound" - to sound out together with a loud sound. Resonance is a

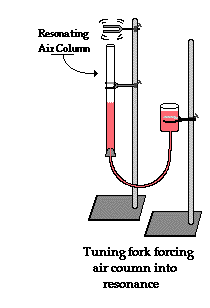

common cause of sound production in musical instruments. One of our best models

of resonance in a musical instrument is a resonance tube (a  hollow cylindrical tube) partially filled with water and forced into

vibration by a tuning fork. The tuning fork is the object that forced the air

inside of the resonance tube into resonance. As the tines of the tuning fork

vibrate at their own natural frequency, they created sound waves that impinge

upon the opening of the resonance tube. These impinging sound waves produced by

the tuning fork force air inside of the resonance tube to vibrate at the same

frequency. Yet, in the absence of resonance, the sound of these vibrations is

not loud enough to discern. Resonance only occurs when the first object is

vibrating at the natural frequency of the second object. So if the frequency at

which the tuning fork vibrates is not identical to one of the natural

frequencies of the air column inside the resonance tube, resonance will not

occur and the two objects will not sound out together with a loud sound. But

the location of the water level can be altered by raising and lowering a

reservoir of water, thus decreasing or increasing the length of the air column. As we have learned

earlier, an increase in the length of a vibrational

system (here, the air in the tube) increases the wavelength and decreases the

natural frequency of that system. Conversely, a decrease in the length of a

vibrational system decreases the wavelength and increases the natural

frequency. So by raising and lowering the water level, the natural frequency of

the air in the tube could be matched to the frequency at which the tuning fork

vibrates. When the match is achieved, the tuning fork forces the air column

inside of the resonance tube to vibrate at its own natural frequency and

resonance is achieved. The result of resonance is always a big vibration - that

is, a loud sound.

hollow cylindrical tube) partially filled with water and forced into

vibration by a tuning fork. The tuning fork is the object that forced the air

inside of the resonance tube into resonance. As the tines of the tuning fork

vibrate at their own natural frequency, they created sound waves that impinge

upon the opening of the resonance tube. These impinging sound waves produced by

the tuning fork force air inside of the resonance tube to vibrate at the same

frequency. Yet, in the absence of resonance, the sound of these vibrations is

not loud enough to discern. Resonance only occurs when the first object is

vibrating at the natural frequency of the second object. So if the frequency at

which the tuning fork vibrates is not identical to one of the natural

frequencies of the air column inside the resonance tube, resonance will not

occur and the two objects will not sound out together with a loud sound. But

the location of the water level can be altered by raising and lowering a

reservoir of water, thus decreasing or increasing the length of the air column. As we have learned

earlier, an increase in the length of a vibrational

system (here, the air in the tube) increases the wavelength and decreases the

natural frequency of that system. Conversely, a decrease in the length of a

vibrational system decreases the wavelength and increases the natural

frequency. So by raising and lowering the water level, the natural frequency of

the air in the tube could be matched to the frequency at which the tuning fork

vibrates. When the match is achieved, the tuning fork forces the air column

inside of the resonance tube to vibrate at its own natural frequency and

resonance is achieved. The result of resonance is always a big vibration - that

is, a loud sound.

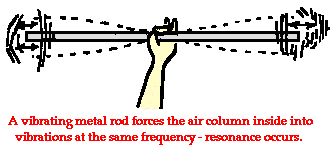

Another common physics demonstration that serves as an

excellent model of resonance is the famous "singing rod" demonstration. A long

hollow aluminum rod is held at its center. Being a trained musician, teacher reaches in a

rosin bag to prepare for the event. Then with great enthusiasm, he/she slowly

slides her hand across the length of the aluminum rod, causing it to sound out with a loud

sound. This is an example of resonance. As the hand slides across the surface

of thealuminum rod, slip-stick frictionbetween the hand and the rod produces vibrations of

the aluminum. The vibrations of the aluminum force the air column inside of the rod to

vibrate at its natural frequency. The match between the vibrations of the air

column and one of the natural frequencies of the singing rod causes resonance. The result of

resonance is always a big vibration - that is, a loud sound.

The familiar sound

of the sea that is heard when

a seashell is placed up to your ear is also explained by resonance. Even in an

apparently quiet room, there are sound waves with a range of frequencies. These

sounds are mostly inaudible due to their low intensity. This so-called

background noise fills the seashell, causing vibrations within the seashell.

But the seashell has a set of natural frequencies at which it will vibrate. If

one of the frequencies in the room forces air within the seashell to vibrate at

its natural frequency, a resonance situation is created. And always, the

result of resonance is a big vibration - that is, a loud sound. In fact, the sound

is loud enough to hear. So the next time you hear the sound of the sea in a seashell, remember that all that

you are hearing is the amplification of one of the many background frequencies

in the room.

Resonance and

Musical Instruments

Resonance and

Musical Instruments

Musical instruments produce their selected sounds in the same

manner. Brass instruments typically consist of a mouthpiece attached to a long

tube filled with air. The tube is often curled in order to reduce the size of

the instrument. The metal tube merely serves as a container for a column of

air. It is the vibrations of this column that produces the sounds that we hear.

The length of the vibrating air column inside the tube can be adjusted either

by sliding the tube to increase and decrease its length or by opening and

closing holes located along the tube in order to control where the air enters

and exits the tube. Brass instruments involve the blowing of air into a

mouthpiece. The vibrations of the lips against the mouthpiece produce a range

of frequencies. One of the frequencies in the range of frequencies matches one

of the natural frequencies of the air column inside of the brass instrument.

This forces the air inside of the column into resonance vibrations. The result of

resonance is always a big vibration - that is, a loud sound.

Woodwind instruments operate in a similar manner. Only, the

source of vibrations is not the lips of the musician against a mouthpiece, but

rather the vibration of a reed or wooden strip. The operation

of a woodwind instrument is often modeled in a Physics class using a plastic straw.

The ends of the straw are cut with a scissors, forming a tapered reed. When air is blown through

the reed, the reed vibrates producing turbulence with a range of vibrational

frequencies. When the frequency of vibration of the reed matches the frequency

of vibration of the air column in the straw, resonance occurs. And once more,

the result of resonance is a big vibration - the reed and air column sound out

together to produce a loud sound. As if this weren't silly enough, the length

of the straw is typically shortened by cutting small pieces off its opposite

end. As the straw (and the air column that it contained) is shortened, the

wavelength decreases and the frequency was increases. Higher and higher pitches

are observed as the straw is shortened. Woodwind instruments produce their

sounds in a manner similar to the straw demonstration. A vibrating reed forces

an air column to vibrate at one of its natural frequencies. Only for wind

instruments, the length of the air column is controlled by opening and closing

holes within the metal tube (since the tubes are a little difficult to cut and

a too expensive to replace every time they are cut).

The operation

of a woodwind instrument is often modeled in a Physics class using a plastic straw.

The ends of the straw are cut with a scissors, forming a tapered reed. When air is blown through

the reed, the reed vibrates producing turbulence with a range of vibrational

frequencies. When the frequency of vibration of the reed matches the frequency

of vibration of the air column in the straw, resonance occurs. And once more,

the result of resonance is a big vibration - the reed and air column sound out

together to produce a loud sound. As if this weren't silly enough, the length

of the straw is typically shortened by cutting small pieces off its opposite

end. As the straw (and the air column that it contained) is shortened, the

wavelength decreases and the frequency was increases. Higher and higher pitches

are observed as the straw is shortened. Woodwind instruments produce their

sounds in a manner similar to the straw demonstration. A vibrating reed forces

an air column to vibrate at one of its natural frequencies. Only for wind

instruments, the length of the air column is controlled by opening and closing

holes within the metal tube (since the tubes are a little difficult to cut and

a too expensive to replace every time they are cut).

Resonance is the cause of sound production in musical instruments.

In the remainder of Lesson 5, the mathematics of standing waves will be applied

to understanding how resonating strings and air columns produce their specific

frequencies.