Reflection,

Refraction, and Diffraction

Like any wave, a sound wave doesn't just stop when it

reaches the end of the medium or when it encounters an obstacle in its path.

Rather, a sound wave will undergo certain behaviors when

it encounters the end of the medium or an obstacle. Possible behaviors include reflection off the obstacle,

diffraction around the obstacle, and transmission (accompanied by refraction)

into the obstacle or new medium. In this part of Lesson 3, we will

investigate behaviors that have already been

discussed in a previous unit and apply them towards the reflection,

diffraction, and refraction of sound waves.

Reflection

and Transmission of Sound

When a wave reaches the boundary between one medium another

medium, a portion of the wave undergoes reflection and a portion of the wave

undergoes transmission across the boundary. As discussed in the previous

part of Lesson 3, the amount of reflection is dependent upon

the dissimilarity of the two media. For this reason, acoustically minded

builders of auditoriums and concert halls avoid the use of hard, smooth

materials in the construction of their inside halls. A hard material such as

concrete is as dissimilar as can be to the air through which the sound moves;

subsequently, most of the sound wave is reflected by the walls and little is absorbed.

Walls and ceilings of concert halls are made softer materials such as

fiberglass and acoustic tiles. These materials are more similar to air than

concrete and thus have a greater ability to absorb sound. This gives the room

more pleasing acoustic properties.

in the previous

part of Lesson 3, the amount of reflection is dependent upon

the dissimilarity of the two media. For this reason, acoustically minded

builders of auditoriums and concert halls avoid the use of hard, smooth

materials in the construction of their inside halls. A hard material such as

concrete is as dissimilar as can be to the air through which the sound moves;

subsequently, most of the sound wave is reflected by the walls and little is absorbed.

Walls and ceilings of concert halls are made softer materials such as

fiberglass and acoustic tiles. These materials are more similar to air than

concrete and thus have a greater ability to absorb sound. This gives the room

more pleasing acoustic properties.

Reflection of sound waves off of surfaces can lead to one of

two phenomena - an echo or a reverberation. A

reverberation often occurs in a small room with height, width, and length

dimensions of approximately 17 meters or less. Why the magical 17 meters? The

effect of a particular sound wave upon the brain endures for more than a tiny

fraction of a second; the human brain keeps a sound in memory for up to 0.1

seconds. If a reflected sound wave reaches the ear within 0.1 seconds of the

initial sound, then it seems to the person that the sound is prolonged. The reception of multiple reflections off of walls and ceilings within

0.1 seconds of each other causes reverberations - the prolonging of a sound.

Since sound waves travel at about 340 m/s at room temperature, it will take

approximately 0.1 s for a sound to travel the length of a 17 meter room and

back, thus causing a reverberation (recall from Lesson

2, t = d/v = (34 m)/(340 m/s) = 0.1 s). This is why

reverberations are common in rooms with dimensions of approximately 17 meters or

less. Perhaps you have observed reverberations when talking in an empty room,

when honking the horn while driving through a highway tunnel or underpass, or

when singing in the shower. In auditoriums and concert halls, reverberations

occasionally occur and lead to the displeasing garbling of a sound.

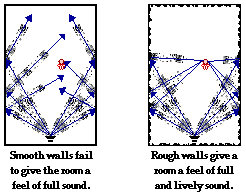

But reflection of sound waves in auditoriums and concert

halls do not always lead to displeasing results, especially if the reflections

are designed right. Smooth walls

have a tendency to direct sound waves in a specific direction. Subsequently the

use of smooth walls in an auditorium will cause spectators to receive a large

amount of sound from one location along the wall; there would be only one

possible path by which sound waves could travel from the speakers to the

listener. The auditorium would not seem to be as lively and full of sound.

Rough walls tend to diffuse sound, reflecting it in a variety of directions.

This allows a spectator to perceive sounds from every part of the room, making

it seem lively and full. For this reason, auditorium and concert hall designers

prefer construction materials that are rough rather than smooth.

Reflection of sound waves also leads to echoes. Echoes are different than reverberations. Echoes occur when a

reflected sound wave reaches the ear more than 0.1 seconds after the original

sound wave was heard. If the elapsed time between the arrivals of the two sound

waves is more than 0.1 seconds, then the sensation of the first sound will have died out. In this case, the arrival of the second sound wave will be perceived

as a second sound rather than the prolonging of the first sound. There will be

an echo instead of a reverberation.

Reflection of sound waves off of surfaces is also affected by

the shape of the surface. As mentioned of water waves

in Unit 10, flat or plane surfaces reflect sound waves in

such a way that the angle at which the wave approaches the surface equals the

angle at which the wave leaves the surface. This principle will be extended to

the reflective behavior of light waves off

of plane surfaces in great detail in Unit 13 of The Physics Classroom. Reflection of sound waves off of curved surfaces leads to a more

interesting phenomenon. Curved surfaces with a parabolic shape have the habit

of focusing sound waves to a point. Sound waves reflecting off of parabolic

surfaces concentrate all their energy to a single point in space; at that

point, the sound is amplified. Perhaps you have seen a museum exhibit that

utilizes a parabolic-shaped disk to collect a large amount of sound and focus

it at a focal point. If you place your ear at the focal point, you

can hear even the faintest whisper of a friend standing across the room.

Parabolic-shaped satellite disks use this same principle of reflection to

gather large amounts of electromagnetic waves and focus it at a point (where

the receptor is located). Scientists have recently discovered some evidence

that seems to reveal that a bull moose utilizes his antlers as a satellite disk

to gather and focus sound. Finally, scientists have long believed that owls are

equipped with spherical facial disks that can be maneuvered in

order to gather and reflect sound towards their ears. The reflective behavior of light waves off curved surfaces will be

studies in great detail in Unit 13 of The Physics Classroom Tutorial.

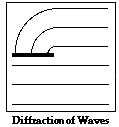

Diffraction of Sound Waves

Diffraction involves a change in direction of waves as they

pass through an opening or around a barrier in their path. The diffraction

of water waves was discussed in Unit 10 of The Physics Classroom Tutorial. In that

unit, we saw that water waves have the ability to travel around corners, around

obstacles and through openings. The amount of diffraction (the sharpness of the

bending) increases with increasing wavelength and decreases with decreasing

wavelength. In fact, when the wavelength of the wave is smaller than the

obstacle or opening, no noticeable diffraction occurs.

Diffraction of sound waves is commonly observed; we notice sound

diffracting around corners or through door openings, allowing us to hear others

who are speaking to us from adjacent rooms. Many forest-dwelling birds take

advantage of the diffractive ability of long-wavelength sound waves. Owls for

instance are able to communicate across long distances due to the fact that

their long-wavelength hoots are able

to diffract around forest trees and carry farther than the short-wavelength tweets of

songbirds. Low-pitched (long wavelength) sounds always carry further than

high-pitched (short wavelength) sounds.

Diffraction of sound waves is commonly observed; we notice sound

diffracting around corners or through door openings, allowing us to hear others

who are speaking to us from adjacent rooms. Many forest-dwelling birds take

advantage of the diffractive ability of long-wavelength sound waves. Owls for

instance are able to communicate across long distances due to the fact that

their long-wavelength hoots are able

to diffract around forest trees and carry farther than the short-wavelength tweets of

songbirds. Low-pitched (long wavelength) sounds always carry further than

high-pitched (short wavelength) sounds.

Scientists have recently learned that elephants emit

infrasonic waves of very low frequency to communicate over long distances to

each other. Elephants typically migrate in large herds that may sometimes

become separated from each other by distances of several miles. Researchers who

have observed elephant migrations from the air and have been both impressed and

puzzled by the ability of elephants at the beginning and the end of these herds

to make extremely synchronized movements. The matriarch at the front of the

herd might make a turn to the right, which is immediately followed by elephants

at the end of the herd making the same turn to the right. These synchronized

movements occur despite the fact that the elephants' vision of each other is

blocked by dense vegetation. Only recently have they learned that the

synchronized movements are preceded by infrasonic communication. While low

wavelength sound waves are unable to diffract around the dense vegetation, the

high wavelength sounds produced by the elephants have sufficient diffractive

ability to communicate long distances.

Bats use high frequency (low wavelength) ultrasonic waves in

order to enhance their ability to hunt. The typical prey of a bat is the moth -

an object not much larger than a couple of centimeters.

Bats use ultrasonic echolocation methods to detect the presence of bats in the

air. But why ultrasound? The answer lies in the physics of diffraction. As the

wavelength of a wave becomes smaller than the obstacle that it encounters, the

wave is no longer able to diffract around the obstacle, instead the wave

reflects off the obstacle. Bats use ultrasonic waves with wavelengths smaller

than the dimensions of their prey. These sound waves will encounter the prey,

and instead of diffracting around the prey, will reflect off the prey and allow

the bat to hunt by means of echolocation. The wavelength of a 50 000 Hz sound

wave in air (speed of approximately 340 m/s) can be calculated as follows

wavelength = speed/frequency

wavelength = (340

m/s)/(50 000 Hz)

wavelength = 0.0068 m

The wavelength of the 50 000 Hz sound wave (typical for a

bat) is approximately 0.7 centimeters, smaller

than the dimensions of a typical moth.

Refraction

of Sound Waves

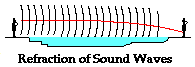

Refraction of waves involves a change in the direction of

waves as they pass from one medium to another. Refraction, or bending of the

path of the waves, is accompanied by a change in speed and wavelength of the

waves. So if the media (or its properties) are changed, the speed of the wave

is changed. Thus, waves passing from one medium to another will undergo

refraction. Refraction of sound waves is most evident in situations in which

the sound wave passes through a medium with gradually varying properties. For

example, sound waves are known to refract when traveling over water. Even

though the sound wave is not exactly changing media, it is traveling through a

medium with varying properties; thus,

the wave will encounter refraction and change its direction. Since water has a

moderating effect upon the temperature of air, the air directly above the water

tends to be cooler than the air far above the water. Sound waves travel slower

in cooler air than they do in warmer air. For this reason, the portion of

the wavefrontdirectly above the water is slowed

down, while the portion of the wavefronts far

above the water speeds ahead. Subsequently, the direction of the wave changes,

refracting downwards towards the water. This is depicted in the diagram at the

right.

properties; thus,

the wave will encounter refraction and change its direction. Since water has a

moderating effect upon the temperature of air, the air directly above the water

tends to be cooler than the air far above the water. Sound waves travel slower

in cooler air than they do in warmer air. For this reason, the portion of

the wavefrontdirectly above the water is slowed

down, while the portion of the wavefronts far

above the water speeds ahead. Subsequently, the direction of the wave changes,

refracting downwards towards the water. This is depicted in the diagram at the

right.

Refraction of other waves such as light waves will be

discussed in more detail in a later unit of The Physics Classroom Tutorial.