Electric Fields

Action at a Distance

The underlying and primary question being addressed in this

unit of The Physics Classroom is: How can an object be charged and what effect

does that charge have upon other objects in its vicinity? Early in  Lesson 1, we investigated charge interactions - the

effect of a charged object upon other objects of the same type of charge, of an

opposite type of charge and of no charge whatsoever. In Lesson 3, the concept of the interaction between charges was revisited and Coulomb's

law was introduced to express charge interactions in quantitative terms. In

Lesson 3, electric force was described as a non-contact force. A charged

balloon can have an attractive effect upon an oppositely charged balloon even

when they are not in contact. The electric force acts over the distance

separating the two objects. Electric force is an action-at-a-distance force. In

Lesson 4 of this unit, we will explore this concept of action-at-a-distance using a

different concept known as the electric field. As is

the usual case, we will begin conceptually and then enter into mathematical

expressions that express the concept of an electric field in mathematical

terms.

Lesson 1, we investigated charge interactions - the

effect of a charged object upon other objects of the same type of charge, of an

opposite type of charge and of no charge whatsoever. In Lesson 3, the concept of the interaction between charges was revisited and Coulomb's

law was introduced to express charge interactions in quantitative terms. In

Lesson 3, electric force was described as a non-contact force. A charged

balloon can have an attractive effect upon an oppositely charged balloon even

when they are not in contact. The electric force acts over the distance

separating the two objects. Electric force is an action-at-a-distance force. In

Lesson 4 of this unit, we will explore this concept of action-at-a-distance using a

different concept known as the electric field. As is

the usual case, we will begin conceptually and then enter into mathematical

expressions that express the concept of an electric field in mathematical

terms.

Electric

Forces as Non-Contact Forces

At the time that the concept of force was introduced in Unit 2 of

The Physics Classroom, it was mentioned that there are two

categories of forces - contact forces and non-contact forces. Electrical force

and gravitational force were both listed as non-contact forces. The gravitational

force, discussed in detail inUnit 6 of The Physics Classroom Tutorial, is a force that most of us are familiar with. Gravitational forces are

action-at-a-distance forces that act between two objects even when they are

held some distance apart. If you watch a roller coaster car move along its

course, then you are witnessing an action-at-a-distance. The Earth and the

coaster car attract even though there is no physical contact between the two

objects. If you watch a baseball travel its parabolic trajectory at a baseball

park, then you are witnessing an action-at-a-distance. The Earth and the

baseball attract even though there is no physical contact between the two

objects. If you watch the digested lunch of a Canadian goose land on your newly

washed car, then you are witnessing (the end result of) an

action-at-a-distance. The Earth and the goose do attract

even though there is no physical contact between the two objects. In each of

these examples, the mass of the Earth exerted an influence over a distance,

affecting other objects of mass that were in the surroundingneighborhood.

The action-at-a-distance nature of the electrical force is

commonly observed numerous times during lab activities and demonstrations in a

Physics classroom. A charged plastic golf tube might be held above bits of

paper on a lab bench. The plastic tube attracts the paper bits even though

physical contact is not made with the paper bits. The  charged plastic tube might also be held near a charged rubber balloon;

and even without physical contact, the tube and the balloon act over a

distance. The charged plastic tube exerts its influence over a distance,

affecting other charged objects that were in the surrounding neighborhood. Consider a charged foam

plate held above an aluminum pie plate

without touching it. The charged foam plate exerts an influence upon charged

electrons in the aluminum plate even though

physical contact is not made. The charged foam plate exerts its influence over

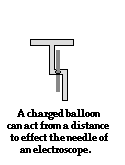

a distance, affecting other charged objects in the surrounding neighborhood. Consider a physics

demonstration in which a charged object is brought near the plate of a needle

electroscope. Prior to any contact between the electroscope plate and the

charged object, the needle of the electroscope begins to deflect. The charged

object exerts an influence upon charged electrons in the electroscope even

though physical contact is not made. The charged object affects other charged

objects that were in the surroundingneighborhood.

charged plastic tube might also be held near a charged rubber balloon;

and even without physical contact, the tube and the balloon act over a

distance. The charged plastic tube exerts its influence over a distance,

affecting other charged objects that were in the surrounding neighborhood. Consider a charged foam

plate held above an aluminum pie plate

without touching it. The charged foam plate exerts an influence upon charged

electrons in the aluminum plate even though

physical contact is not made. The charged foam plate exerts its influence over

a distance, affecting other charged objects in the surrounding neighborhood. Consider a physics

demonstration in which a charged object is brought near the plate of a needle

electroscope. Prior to any contact between the electroscope plate and the

charged object, the needle of the electroscope begins to deflect. The charged

object exerts an influence upon charged electrons in the electroscope even

though physical contact is not made. The charged object affects other charged

objects that were in the surroundingneighborhood.

The

Electric Field Concept

As children grow, they become very accustomed to contact

forces; but an action-at-a-distance force upon first observation is quite

surprising. Seeing two charged balloons repel from a distance or two magnets

attract from a distance raises the eyebrow of a child and maybe even causes a

chuckle or a "wow." Indeed, an action-at-a-distance or non-contact

force is quite unusual. Football players don't run down the field and encounter

collision forces from five yards apart. The rear-end collision at a stop sign

is not characterized by repulsive forces that act upon the colliding cars at a

spatial separation of 10 meters. And (with the exception modern WWF wrestling

matches) the fist of one fighter does not act from 12 inches away to cause the

forehead of a second fighter to be knocked backwards. Contact forces are quite

usual and customary to us. Explaining a contact force that we all feel and

experience on a daily basis is not difficult. Non-contact forces require a more

difficult explanation. After all, how can one balloon reach across space and

pull a second balloon towards it or push it away? The best explanation to this

question involves the introduction of the concept of electric field.

Action-at-a-distance forces are sometimes referred to as

field forces. The concept of a field force is

utilized by scientists to explain this rather unusual force phenomenon that

occurs in the absence of physical contact. While all masses attract when held

some distance apart, charges can either repel or attract when held some

distance apart. An alternative to describing this action-at-a-distance effect

is to simply suggest that there is something rather strange about the space

surrounding a charged object. Any other charged object that is in that space

feels the effect of the charge. A charged object creates an electric field - an

alteration of the space in the region that surrounds it. Other charges in that

field would feel the unusual alteration of the space. Whether a charged object

enters that space or not, the electric field exists. Space is altered by the

presence of a charged object. Other objects in that space experience the

strange and mysterious qualities of the space.

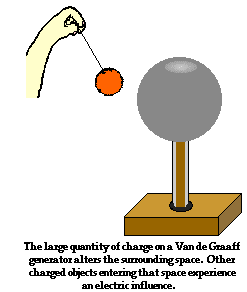

The strangeness of the space surrounding a charged object is

often experienced first hand by the use of

a Van de Graaff generator. A Van de Graaff generator is a large conducting sphere that

acquires a charge as electrons are scuffed off of a rotating belt as it moves

past sharp elongated prongs inside the sphere. The buildup of

static charge on the Van de Graaff generator

is much greater than that on a balloon rubbed with animal fur or an aluminum plate charged by induction. On a dry day,

the buildup of charge becomes so great that

it can exert influences on charged balloons held some distance away. If you

were to walk near a Van de Graaff generator

and hold out your hand, you might even notice the hairs on your hand standing

up. And if you were to slowly walk near a

Van de Graaff generator, your eyebrows

might begin to feel quitestaticy. The Van

de Graaff generator, like any charged

object, alters the space surrounding it. Other charged objects entering the

space feel the strangeness of that space. Electric forces are exerted upon

those charged objects when they enter that space. The Van de Graaff generator is said to create an electric field

in the space surrounding it.

A Stinky Analogy

With a concept such as the electric field, analogies are

often appropriate and useful. While the following analogy might be a wee-bit crude, it

certainly proves useful in many respects in describing the nature of an

electric field. Anyone who has ever walked into a room of an infant with a

soiled diaper (as in a poopydiaper) has

experienced a stinky field. There is something about the space

surrounding an infant's soiled diaper that exerts a strange influence upon

other people who enter that space. When that little stinkerneeds a diaper change, you can't help but to

notice it. When you walk into a room with such a diaper present, your detectors

(i.e., the nose) begin to detect the presence of a stinky field. As you move

closer and closer to the infant, the stinky field becomes more and more

intense. And of course the worse the diaper, the stronger the stinky field

becomes. It's not difficult to imagine that a soiled diaper could exert a

smelly influence some distance away that would repel any nose that gets in that

area. The diaper has altered the nature of the surrounding space and when your

nose gets near, you know it. The stinky diaper has created a stinky field.

In the same manner, an electric charge creates an electric

field - it has altered the nature of the space surrounding the charge. And if

another charge gets near enough, that charge will sense that there is an effect

when present in that surrounding space. And electric field is sensed by the

detector charge in the same way that a nose senses the stinky field. The

strength of the stinky field is dependent upon the distance from the stinky

diaper and the amount of stinky in the

diaper. And in an analogous manner, the strength of the electric field is

dependent upon the amount of charge that creates the field and the distance

from the charge.

Now all of a sudden, the discussion of electric field begins

to take on a quantitative nature. Some electric fields are stronger or more

intense than others. And perhaps the strength of the electric field could be

measured and quantified. And clearly charge and distance seem to be two

variables that affect the strength of an electric field. the quantitative nature of electric field will be

discussed. The question of "How can the strength of an electric field be

quantified?" will be explored. We will move beyond the mere concept of the

electric field to the mathematics of the electric field.