Relativistic Addition of Velocities

Figure 1. The total velocity of a kayak, like this one on the Deerfield River in Massachusetts, is its velocity relative to the water as well as the water’s velocity relative to the riverbank

If you’ve ever seen a kayak move down a fast-moving river, you know that remaining in the same place would be hard. The river current pulls the kayak along. Pushing the oars back against the water can move the kayak forward in the water, but that only accounts for part of the velocity. The kayak’s motion is an example of classical addition of velocities. In classical physics, velocities add as vectors. The kayak’s velocity is the vector sum of its velocity relative to the water and the water’s velocity relative to the riverbank.

Classical Velocity Addition

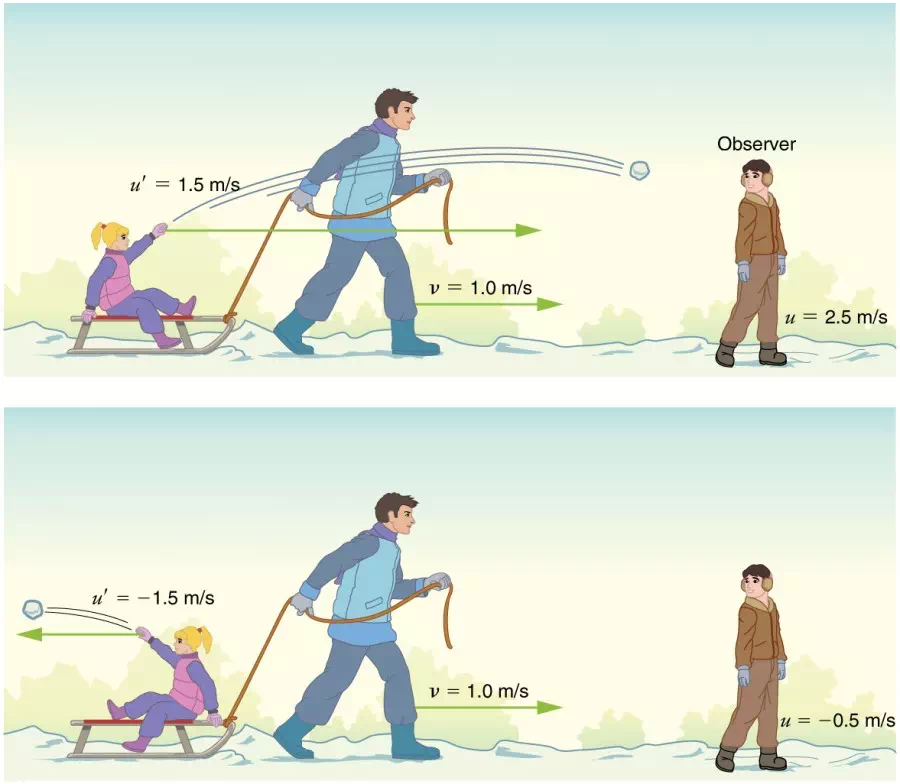

For simplicity, we restrict our consideration of velocity addition to one-dimensional motion. Classically, velocities add like regular numbers in one-dimensional motion. (See Figure 2.) Suppose, for example, a girl is riding in a sled at a speed 1.0 m/s relative to an observer. She throws a snowball first forward, then backward at a speed of 1.5 m/s relative to the sled. We denote direction with plus and minus signs in one dimension; in this example, forward is positive. Let v be the velocity of the sled relative to the Earth, u the velocity of the snowball relative to the Earth-bound observer, and u′ the velocity of the snowball relative to the sled.

Figure 2. Classically, velocities add like ordinary numbers in one-dimensional motion. Here the girl throws a snowball forward and then backward from a sled. The velocity of the sled relative to the Earth is v = 1.0 m/s. The velocity of the snowball relative to the truck is u′, while its velocity relative to the Earth is u. Classically, u = v + u′.

CLASSICAL VELOCITY ADDITION

u = v + u′

Thus, when the girl throws the snowball forward, u = 1.0 m/s + 1.5 m/s = 2.5 m/s. It makes good intuitive sense that the snowball will head towards the Earth-bound observer faster, because it is thrown forward from a moving vehicle. When the girl throws the snowball backward, u = 1.0 m/s + (−1.5 m/s) = −0.5 m/s. The minus sign means the snowball moves away from the Earth-bound observer.

Relativistic Velocity Addition

The second postulate of relativity (verified by extensive experimental observation) says that classical velocity addition does not apply to light. Imagine a car traveling at night along a straight road, as in Figure 3. If classical velocity addition applied to light, then the light from the car’s headlights would approach the observer on the sidewalk at a speed u = v + c. But we know that light will move away from the car at speed c relative to the driver of the car, and light will move towards the observer on the sidewalk at speed c, too.

Figure 3. According to experiment and the second postulate of relativity, light from the car’s headlights moves away from the car at speed c and towards the observer on the sidewalk at speed c. Classical velocity addition is not valid.

RELATIVISTIC VELOCITY ADDITION

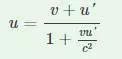

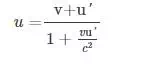

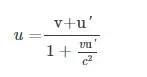

Either light is an exception, or the classical velocity addition formula only works at low velocities. The latter is the case. The correct formula for one-dimensional relativistic velocity addition is

where v is the relative velocity between two observers, u is the velocity of an object relative to one observer, and u′ is the velocity relative to the other observer. (For ease of visualization, we often choose to measure u in our reference frame, while someone moving at v relative to us measures u′.) Note that the term

gives a result very close to classical velocity addition. As before, we see that classical velocity addition is an excellent approximation to the correct relativistic formula for small velocities. No wonder that it seems correct in our experience.

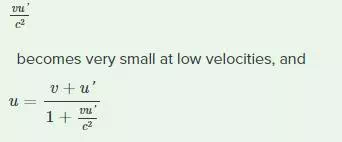

EXAMPLE 1. SHOWING THAT THE SPEED OF LIGHT TOWARDS AN OBSERVER IS CONSTANT (IN A VACUUM): THE SPEED OF LIGHT IS THE SPEED OF LIGHT

Suppose a spaceship heading directly towards the Earth at half the speed of light sends a signal to us on a laser-produced beam of light. Given that the light leaves the ship at speed c as observed from the ship, calculate the speed at which it approaches the Earth.

Figure 4.

Strategy

Because the light and the spaceship are moving at relativistic speeds, we cannot use simple velocity addition. Instead, we can determine the speed at which the light approaches the Earth using relativistic velocity addition.

Solution

Identify the knowns: v = 0.500c; u′=c

Identify the unknown: u

Choose the appropriate equation:

Discussion

Relativistic velocity addition gives the correct result. Light leaves the ship at speed c and approaches the Earth at speed c. The speed of light is independent of the relative motion of source and observer, whether the observer is on the ship or Earth-bound.

Velocities cannot add to greater than the speed of light, provided that v is less than c and u′ does not exceed c. Example 2 illustrates that relativistic velocity addition is not as symmetric as classical velocity addition.

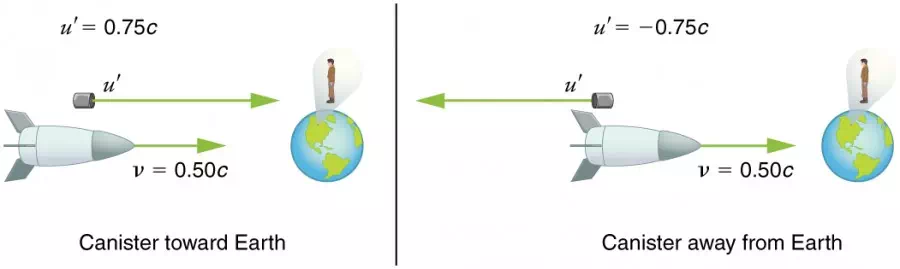

EXAMPLE 2. COMPARING THE SPEED OF LIGHT TOWARDS AND AWAY FROM AN OBSERVER: RELATIVISTIC PACKAGE DELIVERY

Suppose the spaceship in the previous example is approaching the Earth at half the speed of light and shoots a canister at a speed of 0.750c.

1. At what velocity will an Earth-bound observer see the canister if it is shot directly towards the Earth?

2. If it is shot directly away from the Earth? (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5.

Strategy

Because the canister and the spaceship are moving at relativistic speeds, we must determine the speed of the canister by an Earth-bound observer using relativistic velocity addition instead of simple velocity addition.

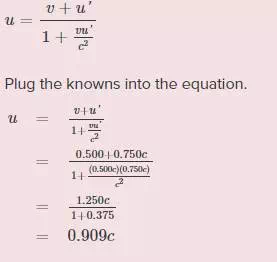

Solution for Part 1

Identify the knowns: v = 0.500c; u′= 0.750c

Identify the unknown: u

Choose the appropriate equation:

Solution for Part 2

Identify the knowns: v = 0.500c; u′ = −0.750c

Identify the unknown: u

Choose the appropriate equation:

Discussion

The minus sign indicates velocity away from the Earth (in the opposite direction from v), which means the canister is heading towards the Earth in Part 1 and away in Part 2, as expected. But relativistic velocities do not add as simply as they do classically. In Part 1, the canister does approach the Earth faster, but not at the simple sum of 1.250c. The total velocity is less than you would get classically. And in Part 2, the canister moves away from the Earth at a velocity of −0.400c, which is faster than the −0.250c you would expect classically. The velocities are not even symmetric. In Part 1 the canister moves 0.409c faster than the ship relative to the Earth, whereas in Part 2 it moves 0.900c slower than the ship.

Doppler Shift

Although the speed of light does not change with relative velocity, the frequencies and wavelengths of light do. First discussed for sound waves, a Doppler shift occurs in any wave when there is relative motion between source and observer.

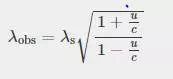

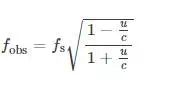

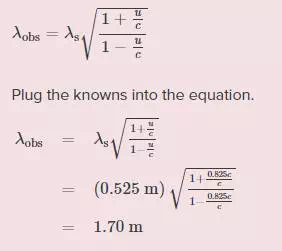

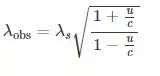

RELATIVISTIC DOPPLER EFFECTS

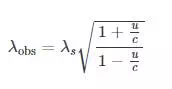

The observed wavelength of electromagnetic radiation is longer (called a red shift) than that emitted by the source when the source moves away from the observer and shorter (called a blue shift) when the source moves towards the observer.

In the Doppler equation, λobs is the observed wavelength, λs is the source wavelength, and u is the relative velocity of the source to the observer. The velocity u is positive for motion away from an observer and negative for motion toward an observer. In terms of source frequency and observed frequency, this equation can be written

Notice that the – and + signs are different than in the wavelength equation.

EXAMPLE 3. CALCULATING A DOPPLER SHIFT: RADIO WAVES FROM A RECEDING GALAXY

Suppose a galaxy is moving away from the Earth at a speed 0.825c. It emits radio waves with a wavelength of 0.525 m. What wavelength would we detect on the Earth?

Strategy

Because the galaxy is moving at a relativistic speed, we must determine the Doppler shift of the radio waves using the relativistic Doppler shift instead of the classical Doppler shift.

Solution

Identify the knowns: u = 0.825c; λs = 0.525 m

Identify the unknown: λobs

Choose the appropriate equation:

Discussion

Because the galaxy is moving away from the Earth, we expect the wavelengths of radiation it emits to be redshifted. The wavelength we calculated is 1.70 m, which is redshifted from the original wavelength of 0.525 m.

The relativistic Doppler shift is easy to observe. This equation has everyday applications ranging from Doppler-shifted radar velocity measurements of transportation to Doppler-radar storm monitoring. In astronomical observations, the relativistic Doppler shift provides velocity information such as the motion and distance of stars.

Section Summary

· With classical velocity addition, velocities add like regular numbers in one-dimensional motion: u = v + u′, where v is the velocity between two observers, u is the velocity of an object relative to one observer, and u′ is the velocity relative to the other observer.

·

Velocities cannot add to be greater than the speed of light.

Relativistic velocity addition describes the velocities of an object moving at

a relativistic speed:

·

An observer of electromagnetic radiation sees relativistic

Doppler effects if the source of the radiation is moving relative to the

observer. The wavelength of the radiation is longer (called a red shift) than

that emitted by the source when the source moves away from the observer and

shorter (called a blue shift) when the source moves toward the observer. The

shifted wavelength is described by the equation

λobs is the observed wavelength, λs is the source wavelength, and u is the relative velocity of the source to the observer.

Glossary

classical velocity addition: the method of adding velocities when v << c; velocities add like regular numbers in one-dimensional motion: u = v + u′, where v is the velocity between two observers, u is the velocity of an object relative to one observer, and u′ is the velocity relative to the other observer

relativistic velocity addition: the method of adding velocities of an object moving at a relativistic speed:

where v is the relative velocity between two observers, u is the velocity of an object relative to one observer, and u′ is the velocity relative to the other observer

relativistic Doppler effects: a change in wavelength of radiation that is moving relative to the observer; the wavelength of the radiation is longer (called a red shift) than that emitted by the source when the source moves away from the observer and shorter (called a blue shift) when the source moves toward the observer; the shifted wavelength is described by the equation

where λobs is the observed wavelength, λs is the source wavelength, and u is the velocity of the source to the observer