Multiple Slit Diffraction

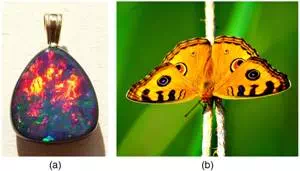

An interesting thing happens if you pass light through a large number of evenly spaced parallel slits, called a diffraction grating. An interference pattern is created that is very similar to the one formed by a double slit. A diffraction grating can be manufactured by scratching glass with a sharp tool in a number of precisely positioned parallel lines, with the untouched regions acting like slits. These can be photographically mass produced rather cheaply. Diffraction gratings work both for transmission of light, as in [link], and for reflection of light, as on butterfly wings and the Australian opal in or the CD pictured in the opening photograph of this chapter, In addition to their use as novelty items, diffraction gratings are commonly used for spectroscopic dispersion and analysis of light. What makes them particularly useful is the fact that they form a sharper pattern than double slits do. That is, their bright regions are narrower and brighter, while their dark regions are darker. shows idealized graphs demonstrating the sharper pattern. Natural diffraction gratings occur in the feathers of certain birds. Tiny, finger-like structures in regular patterns act as reflection gratings, producing constructive interference that gives the feathers colors not solely due to their pigmentation. This is called iridescence.

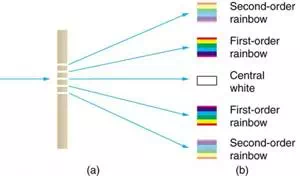

A diffraction grating is a large number of evenly spaced parallel slits. (a) Light passing through is diffracted in a pattern similar to a double slit, with bright regions at various angles. (b) The pattern obtained for white light incident on a grating. The central maximum is white, and the higher-order maxima disperse white light into a rainbow of colors.

(a) This Australian opal and (b) the butterfly wings have rows of reflectors that act like reflection gratings, reflecting different colors at different angles. (credits: (a) Opals-On-Black.com, via Flickr (b) whologwhy, Flickr)

Idealized graphs of the intensity of light passing through a double slit (a) and a diffraction grating (b) for monochromatic light. Maxima can be produced at the same angles, but those for the diffraction grating are narrower and hence sharper. The maxima become narrower and the regions between darker as the number of slits is increased.

The analysis of a diffraction grating is very similar to that

for a double slit (see [link]). As we know from our discussion of double

slits in Young’s Double Slit Experiment, light is diffracted by each slit

and spreads out after passing through. Rays traveling in the same direction (at

an angle  relative to the incident direction)

are shown in the figure. Each of these rays travels a different distance to a

common point on a screen far away. The rays start in phase, and they can be in

or out of phase when they reach a screen, depending on the difference in the

path lengths traveled. As seen in the figure, each ray travels a distance

relative to the incident direction)

are shown in the figure. Each of these rays travels a different distance to a

common point on a screen far away. The rays start in phase, and they can be in

or out of phase when they reach a screen, depending on the difference in the

path lengths traveled. As seen in the figure, each ray travels a distance  different from that of its neighbor,

where

different from that of its neighbor,

where  is the distance between slits. If this

distance equals an integral number of wavelengths, the rays all arrive in

phase, and constructive interference (a maximum) is obtained. Thus, the

condition necessary to obtain constructive interference for a

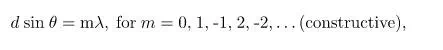

diffraction grating is

is the distance between slits. If this

distance equals an integral number of wavelengths, the rays all arrive in

phase, and constructive interference (a maximum) is obtained. Thus, the

condition necessary to obtain constructive interference for a

diffraction grating is

where  is the distance between slits in the

grating,

is the distance between slits in the

grating,  is the wavelength of light, and

is the wavelength of light, and  is the order of the maximum. Note that

this is exactly the same equation as for double slits separated by

is the order of the maximum. Note that

this is exactly the same equation as for double slits separated by  . However, the slits are usually closer in

diffraction gratings than in double slits, producing fewer maxima at larger

angles.

. However, the slits are usually closer in

diffraction gratings than in double slits, producing fewer maxima at larger

angles.

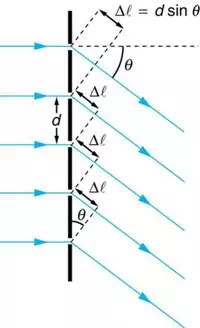

Diffraction grating showing light

rays from each slit traveling in the same direction. Each ray travels a

different distance to reach a common point on a screen (not shown). Each ray

travels a distance  different from that of its neighbor.

different from that of its neighbor.

Where are diffraction gratings used? Diffraction gratings are key components of monochromators used, for example, in optical imaging of particular wavelengths from biological or medical samples. A diffraction grating can be chosen to specifically analyze a wavelength emitted by molecules in diseased cells in a biopsy sample or to help excite strategic molecules in the sample with a selected frequency of light. Another vital use is in optical fiber technologies where fibers are designed to provide optimum performance at specific wavelengths. A range of diffraction gratings are available for selecting specific wavelengths for such use.

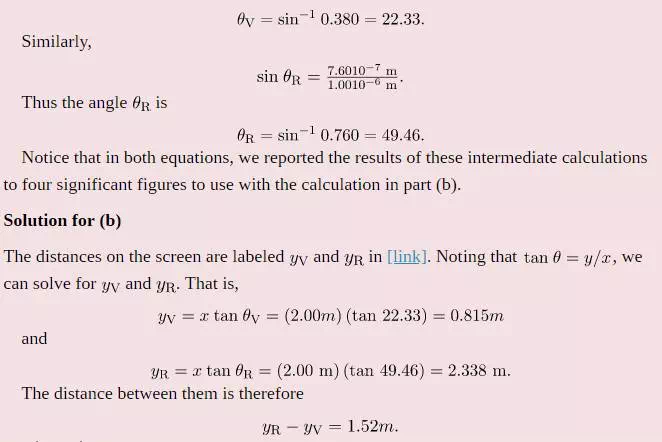

Calculating Typical Diffraction Grating Effects

Diffraction gratings with 10,000 lines per centimeter are readily available. Suppose you have one, and you send a beam of white light through it to a screen 2.00 m away. (a) Find the angles for the first-order diffraction of the shortest and longest wavelengths of visible light (380 and 760 nm). (b) What is the distance between the ends of the rainbow of visible light produced on the screen for first-order interference? (See [link].)

The diffraction grating considered

in this example produces a rainbow of colors on a screen a distance  from the

grating. The distances along the screen are measured perpendicular to the

from the

grating. The distances along the screen are measured perpendicular to the  -direction. In other words, the rainbow

pattern extends out of the page.

-direction. In other words, the rainbow

pattern extends out of the page.

Strategy

The angles can be found using the equation

Discussion

The large distance between the red and violet ends of the rainbow produced from the white light indicates the potential this diffraction grating has as a spectroscopic tool. The more it can spread out the wavelengths (greater dispersion), the more detail can be seen in a spectrum. This depends on the quality of the diffraction grating—it must be very precisely made in addition to having closely spaced lines.

Section Summary

·

.

.