Loom

Loom, machine for weaving cloth. The earliest looms date from the 5th millennium BC and consisted of bars or beams fixed in place to form a frame to hold a number of parallel threads in two sets, alternating with each other. By raising one set of these threads, which together formed the warp, it was possible to run a cross thread, a weft, or filling, between them. The block of wood used to carry the filling strand through the warp was called the shuttle.

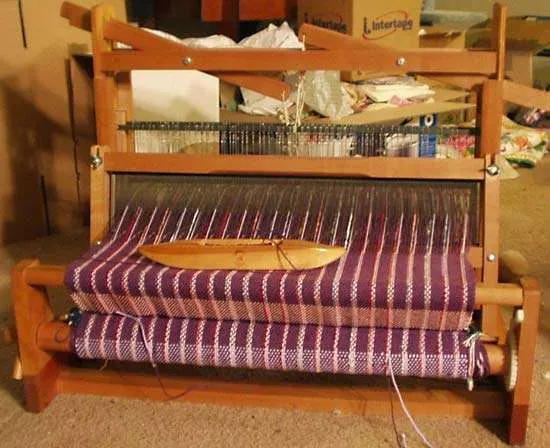

table loom

The fundamental operation of the loom remained unchanged, but a long succession of improvements were introduced through ancient and medieval times in both Asia and Europe. One of the most important of these was the introduction of the heddle, a movable rod that served to raise the upper sheet of warp. In later looms the heddle became a cord, wire, or steel band, several of which could be used simultaneously.

The drawloom, probably invented in Asia for silk weaving, made possible the weaving of more intricate patterns by providing a means for raising warp threads in groups as required by the pattern. The function was at first performed by a boy (the drawboy), but in the 18th century in France the function was successfully mechanized and improved further by the ingenious use of punched cards. Introduced by Jacques de Vaucanson and Joseph-Marie Jacquard, the punched cards programmed the mechanical drawboy, saving labour and eliminating errors. In England, meanwhile, the inventions of John Kay (flying shuttle), Edmund Cartwright (power drive), and others contributed to the Industrial Revolution, in which the loom and other textile machinery played a central role. Modern looms retain the basic operational principles of their predecessors but have added a steadily increasing degree of automatic operation.

Counterparts of these looms were used in many other cultures. A backstrap loom was known in pre-Columbian America and in Asia, and the Navajo Indians wove blankets on a two-bar loom for centuries.