Corrosion

Corrosion is the gradual destruction of a metal in a damp atmosphere by means of simple cell action. In addition to the presence of moisture and air required for rusting, an electrolyte, an anode and a cathode are required for corrosion. Thus, if metals widely spaced in the electrochemical series, are used in contact with each other in the presence of an electrolyte, corrosion will occur. For example, if a brass valve is fitted to a heating system made of steel, corrosion will occur.

The effects of corrosion include the weakening of structures, the reduction of the life of components and materials, the wastage of materials and the expense of replacement.

Corrosion may be prevented by coating with paint, grease, plastic coatings and enamels, or by plating with tin or chromium. Also, iron may be galvanized, i.e., plated with zinc, the layer of zinc helping to prevent the iron from corroding.

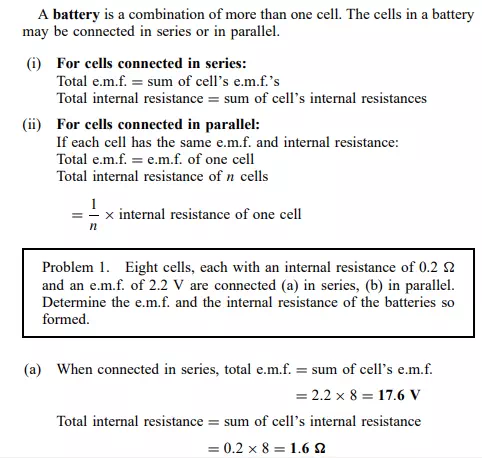

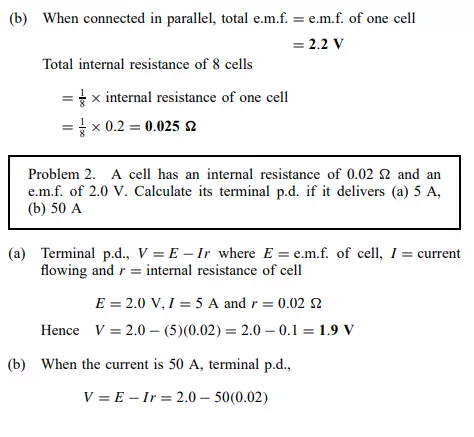

E.m.f. and internal resistance of a cell

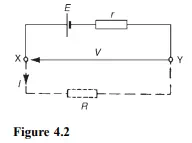

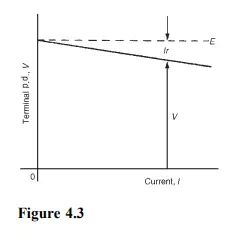

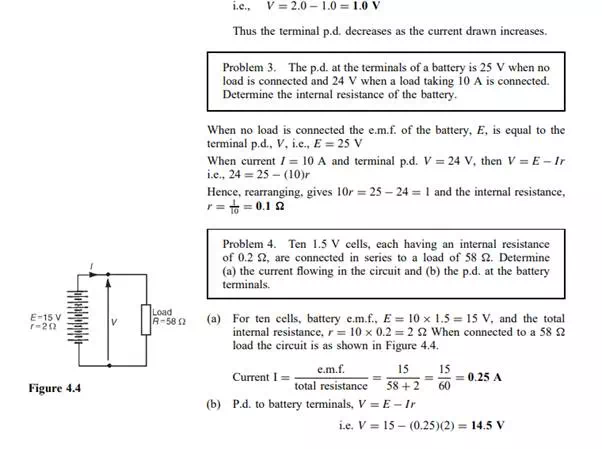

The electromotive force (e.m.f.), E, of a cell is the p.d. between its terminals when it is not connected to a load (i.e. the cell is on ‘no load’). The e.m.f. of a cell is measured by using a high resistance voltmeter connected in parallel with the cell. The voltmeter must have a high resistance otherwise it will pass current and the cell will not be on no-load. For example, if the resistance of a cell is 1 and that of a voltmeter 1 Mthen the equivalent resistance of the circuit is 1 MC 1, i.e. approximately 1 M, hence no current flows and the cell is not loaded. The voltage available at the terminals of a cell falls when a load is connected. This is caused by the internal resistance of the cell which is the opposition of the material of the cell to the flow of current. The internal resistance acts in series with other resistances in the circuit. Figure 4.2 shows a cell of e.m.f. E volts and internal resistance, r, and XY represents the terminals of the cell